Once there was a house standing over here and people living in it. Laughter was heard and there was the swish of dresses and steps scurrying over the stairs; someone would open a window and call the children to the table, in winter it smelled of log fire and in summer of stew. They were all thrown out into the street one spring day without prior notice and scattered away.

The next inhabitants moved into the house. They were many, glum and more savage. These new people wore boots and didn’t draw the entrance door nicely behind themselves anymore: slamming would latch it shut anyways. Strangers to one another and leery, they’d share the bathroom and the kitchen. The eggs and the flour were only for some and did not suffice for all. The house seemed to have more locks and latches now than ever before. A small dog in the yard, some chickens behind the house, and by the end of the summer the cabbage barrel was overturned, so the neighbors would get its smell floating in the air for three days. Crossing old Costache’s yard, rats would pay visits to the hen-coop. They’d quickly steal something from there and run back past the fir tree on their scrawny little feet. Like the new man, they didn’t seem to draw doors closed after themselves anymore: they didn’t need to.

As times changed, these inhabitants disappeared as well. New owners put guards at the gate, so nobody would trespass. They raised the fence higher. Behind it, the house could no longer see into the street. But it didn’t play any role now, all the new owners cared about was its land. The empty house grew more and more sad. Sometimes, a poor man would come hide and sleep upstairs on a mattress, guarded by a shaggy dog. Pigeons had started to nest in the attic.

One night, while everybody was busy with their Christmas baking, the house was set alight. Although you could smell the smoke through the closed windows of the police station on the corner, the firemen took their time to get there and only arrived the next morning… They hosed so much water on the house that its roof came crashing down, taking with it the floor were there once were the children’s rooms and the master bedroom, and bringing it one floor down to the large living room where the Ionescus lived until the 1977 earthquake.

The following winter, people came with machines and razed down what was left. In spring, ashamed, plants struggled to cover the remnants of the house: first a few timid weeds gathered, then the foul smelling ailanthus came with his sisters, the acacias. Together they slowly crawled over the charred pile. Now they’re all hiding behind an even higher fence. Everything is defined by its fence in these times.

Temple of Bel. 2004No situation describes the actual times better: a bunch of uneducated fanatics runs around blowing up in a matter of minutes what has been put up more than 2’000 years ago with more skill and craft than we can deliver today with modern machinery.

Temple of Bel. 2004No situation describes the actual times better: a bunch of uneducated fanatics runs around blowing up in a matter of minutes what has been put up more than 2’000 years ago with more skill and craft than we can deliver today with modern machinery. Great Colonnade at Palmyra, 2004.

Great Colonnade at Palmyra, 2004. A July morning in 2004, 6am

A July morning in 2004, 6am

Altar. Temple of Baalshamin, built in 131AD. 2004.

Altar. Temple of Baalshamin, built in 131AD. 2004. A lizard hiding in the altar wall, 2004

A lizard hiding in the altar wall, 2004 Destruction in 2015. ©REUTERS/Social Media

Destruction in 2015. ©REUTERS/Social Media

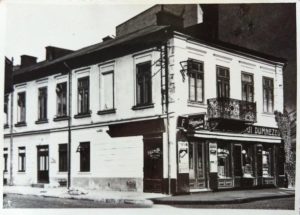

Today I helped grandma out with the Christmas tree. I climbed up the ladder and got the box with the decorations down from the top shelf. The box!… one more piece that survived from the pharmacy!

Today I helped grandma out with the Christmas tree. I climbed up the ladder and got the box with the decorations down from the top shelf. The box!… one more piece that survived from the pharmacy!