Preluat de pe site-ul OAR – https://oar.archi/timbrul-de-arhitectura/de-vorba-in-biblioteca/

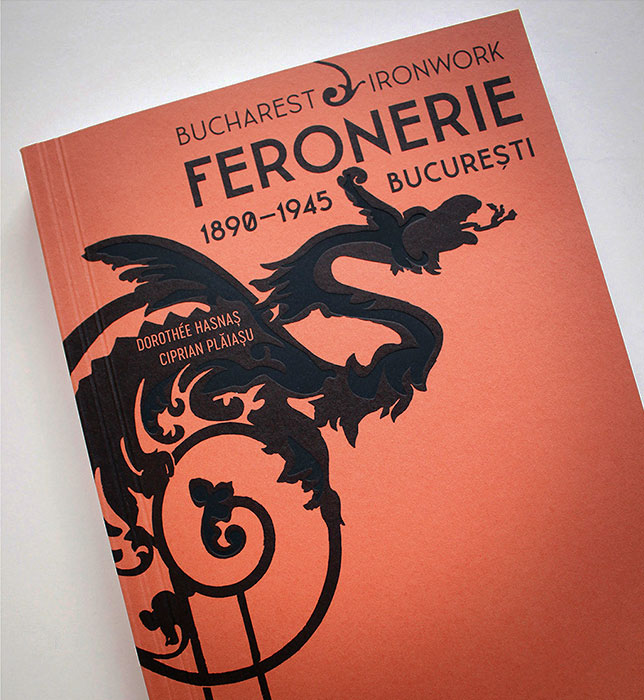

Feronerie. Ironwork. 1890 – 1945 Bucuresti

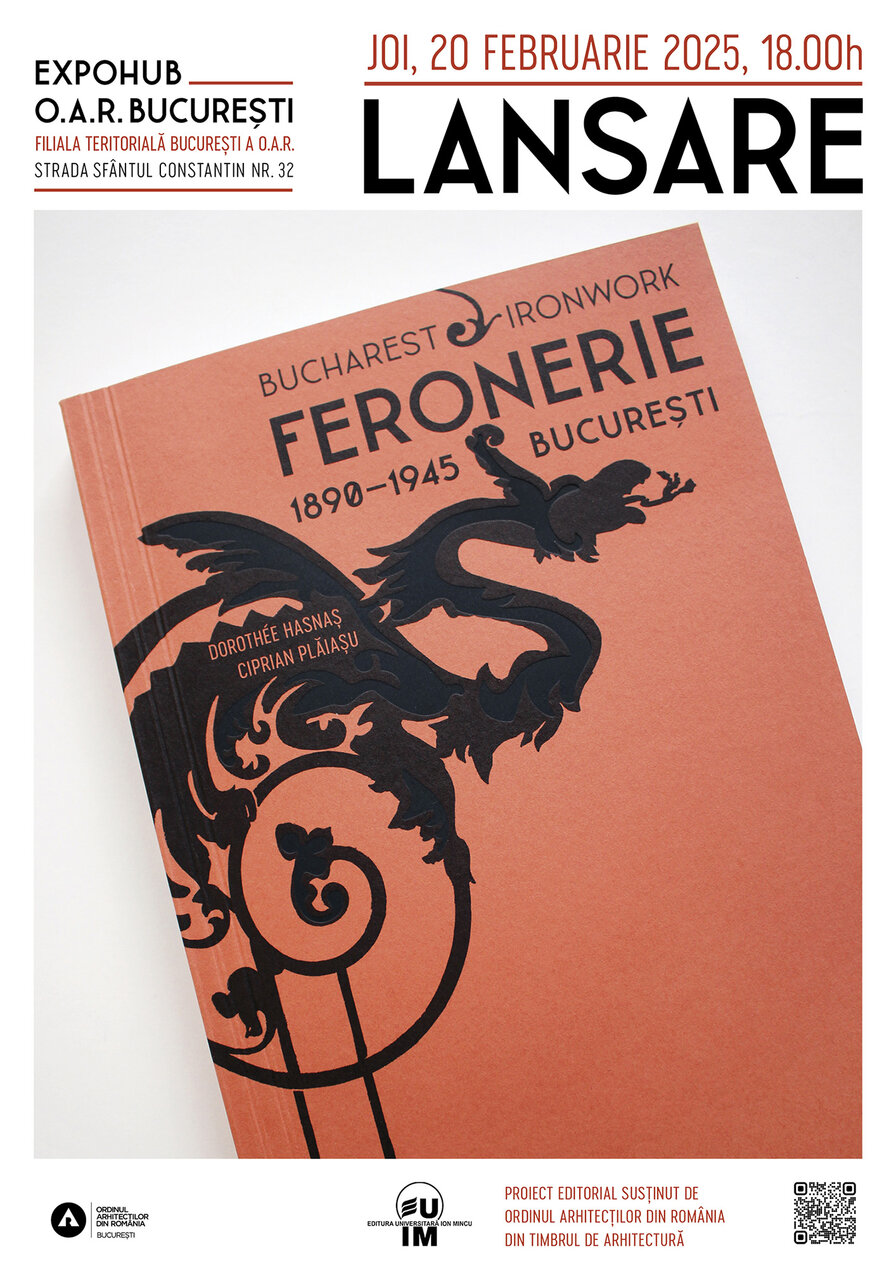

Lansarea cărții „Feronerie. București 1890-1945. Ironwork. Bucharest”

Editura Universitară „Ion Mincu” și Filiala București a OAR anunță lansarea volumului „Feronerie. București 1890-1945. Ironwork. Bucharest”, semnat de arhitecta Dorothée Hasnaș și istoricul Ciprian Plăiașu. Astfel, sunteți invitați la eveniment care are loc joi, 20 februarie, ora 18:00, la sediul Filialei București a OAR, din Str. Sfântul Constantin nr. 32. La eveniment vor participa specialiști în arhitectură, istorie, conservare și patrimoniu, dar și publicul pasionat de identitatea urbană a Capitalei.

De ce o carte despre feroneria bucureșteană?

Această lucrare documentează și analizează feroneria decorativă ca parte esențială a arhitecturii Bucureștiului între 1890 și 1945, o perioadă în care detaliile metalice erau integrate în stiluri diverse – de la eclectismul Belle Époque și neoromânesc, până la Art Deco și modernism. Același meșteșug era aplicat în registre stilistice diferite, reflectând rafinamentul tehnic și creativitatea atelierelor care le produceau.

Volumul subliniază importanța păstrării, întreținerii și restaurării feroneriei vechi, arătând cum aceste detalii sunt nu doar elemente de decor, ci parte din istoria și straturile orașului. Deși extrem de rezistentă în timp, feroneria este fragilă în fața neglijenței și a renovărilor grăbite, fiind prea ușor eliminată de pe fațade și din interioare.

O invitație la descoperire

Cartea propune și un tur pe strada Polonă, un loc unde arhitectura bucureșteană și-a găsit echilibrul între stiluri profund diferite, coexistând în aceeași perioadă istorică. Această diversitate este oglindită și în abordarea feroneriei – fie că vorbim despre balcoane neoromânești cu motive vegetale, garduri Art Deco cu linii dinamice sau scări moderniste cu balustrade minimaliste.

Volumul, realizat cu sprijinul Timbrului de Arhitectură, include peste 120 de imagini și exemple relevante de imobile din cartierele istorice ale Bucureștiului. Totodată, oferă recomandări pentru conservare și un ghid de bune practici, util atât proprietarilor, cât și specialiștilor din domeniu.

Soap. Whiteshirt#16

Soap was one of the things that back in the 80es one would have a hard time obtaining. As everything else deemed as “luxury”: toothpaste, stockings, toilet paper…

There were some old and brittle pieces of soap hidden in grandma`s laundry drawer, but that was “the good soap”, so one was never to use it. It had long ago lost its smell, although grandma would swear she could still detect that fougère or lilly of the valley.

Sometimes in summer my parents would get hold of a piece housemade soap from somebody`s aunt. It was a misterious yellow-greyish chunk that we used for washing everything: our bodies, hair and the laundry. It smelled a bit acrid – “but it`s good for you” – it also left a weird sensation on the skin – I could never imagine how it was obtained just by boiling ashes and grease in a cauldron, but it seemed one could feel the process.

Why couldn`t they throw in some nice smelling flower to the mix? Lindentree or honeysuckle or whatever was growing by the roadside. Flowers were not restricted in any way…

One day a small miracle happened. I went through a drawer and tried to smell a mysterious greenish piece of soap that I had discovered there. It slipped and dropped to the ground, were it broke in two pieces.

Maybe now that it was damaged as an “untouchable memory”, maybe we could use it for washing?

It had a writing on it, so I took it to the sink and made it wet, in order to better decipher the letters on it. Something with Alep.

Once wet, it started smelling: clean-herbal-sweetish-different. It became smooth and shiny. It didn`t reek like the “housemade soap”. It felt nice on the skin.

I used it rarely and always with moderation and respect, for the next ten years: “mit Verstand zu geniessen” was a saying in our family for using valuable things – like chocolate or grandma`s quince jelly, rare finds – so as not to consume it all too fast: to enjoy with reason.

Years later I would actually get the chance to visit a soap manufacture near Aleppo, the place were soap was invented. I got to see how soap emerged in trays and was cut with threads, and walked between lattice walls made of olive-greenish soap chunks that were left out to dry, like brick walls (see it in a filmclip here). Olive and wood ashes (lye). Maybe some laurel oil.

The chunks had the colour of my little nugget from back then – I think I still had a miniature fragment in a drawer back then, in 2004. For the good day that was never to come.

All things have a finite lifetime. So I tossed it one day, as it had completely lost its smell.

Today I found this AlepiDerm soap in a store here in Bucharest. It`s perfect. And it suddenly brought all that back to me: the drawer and the broken soap, the smell of cleanliness and the walk through the Aleppo manufacture. They say, smell goes directly to your cerebellum, the “Kleinhirn“, the oldest part of our brain, not implying the cortex.

It did – and made me happy.

*the store is La Maison du Savon de Marseille, on Dr. Dumitru Râureanu 4, close to Piata Unirii.

This text is part of the WhiteShirtProject: Like a snake sheds its skin, I shed a series of white shirts while writing down memories – to be found in this link.

Bucharest, 2057

An article written for inclusiv.ro in 2020

A text about Bucharest in 2057, when my son will be my current age.

All photographs were taken by Stefan Tuchila as part of the Ultimul Etaj project.

Dear son,

You have won the elections… Congratulations! May it be a momentous occasion.

Somehow, we expected this outcome. Since you were little, I wondered what it would be like for you to one day rise to the leadership of this city that I have cherished so much, that I left behind and rediscovered much later: chaotic, dynamic, and challenging.

In essence, the signs were already present. One summer morning, when you were still in diapers, you went out on the 7th floor terrace of our apartment and proclaimed, “Today, I am the mayor! Come to my office,” and you invited us to the back of the terrace, determined, in your red t-shirt. We laughed, but somehow it felt fitting. You were only two and a half years old, and we were still living on Splai, in the “block of flats with the gods,” where the Dâmbovița River flowed sadly through a canal lined with concrete walls.

Now you have reached the age I was that day. Much has changed in the meantime. I wonder what changes you will bring.

It is widely acknowledged that the future lies in the densification of urban living, in cities, of course. Ultimately, urban life is the most efficient, with shorter commutes and a direct correlation between size and diversity: the larger the city, the more opportunities it offers to all its residents – entertainment, culture, employment, education.

This is the allure of large cities. A metropolis can afford a myriad of establishments, a botanical garden, a university, an opera house, and an excellent public transportation system. However, a metro system is not financially viable for cities with less than a million inhabitants. It is a costly investment that requires a critical mass of users to ensure economic sustainability. As more people rely on public transportation, it becomes increasingly cost-effective. The tram serves as a prime example, being a traditional electric means of transport. If the number of passengers diminishes, the maintenance costs escalate, and neglect becomes more prevalent. If the threshold drops below a certain point, it becomes unaffordable, leading to a scenario where everyone resorts to private cars.

It is often said that a city functions as an efficient organism, but this statement holds true only when it is managed correctly. Ineffectual administration results in public distrust, corruption, political instability, and, ultimately, economic decline and poverty. It perpetuates a vicious cycle, giving rise to vulnerable segments of the population that depend heavily on local governance and become more susceptible to abuses.

Given this context, it is unsurprising that the level of aggression increases in direct proportion to the complexities citizens face when attempting to access basic services. That is why most cities consistently ranking in the top 10 for quality of life statistics are located in Switzerland and Germany, while Bucharest traditionally occupies a place in the lower half of the spectrum.

Vienna and Zurich have been vying for the top spot for years, cities where navigation is seamless and citizens have faith in their local authorities, who, in turn, treat them with respect and attentiveness. They serve as exemplars of good governance, often fostering citizen participation. Residents of various neighborhoods actively contribute to decision-making processes and the city’s overall functioning, alongside professionals, while administrative decisions are made transparently. In Bucharest, civic initiative groups emerged from conflicts of interest between municipal administrations and citizens, dating back to 2010.

As you assume the role of mayor in 2057, I hope you will strive to bring about positive change in Bucharest. Lead with integrity, inclusivity, and a vision for a city that places the well-being and aspirations of its residents at the forefront. Embrace participatory governance and transparency, working towards creating an environment where people can thrive, discover opportunities, and live fulfilled lives.

I have unwavering confidence in your ability to make a difference. Remember to lend an ear to the voices of the people, collaborate with experts, and exhibit courage in your decision-making. Bucharest possesses immense potential, and under your guidance, it has the opportunity to become a city that we can genuinely take pride in.

© Ștefan Tuchilă, ultimul Etaj

When the last major earthquake struck in 2027, you were 10 years old. The administration monumentally failed to cope with the disaster, resulting in a significant increase in casualties, similar to what happened during the Colectiv nightclub fire in 2015, two years before you were born, where more people died in hospitals than in the actual fire. Since then, Bucharest residents have learned, and civil society has organized itself better, getting involved in preparedness operations for diseases and response to earthquakes.

The 2020s were a turbulent decade: it began with the Covid-19 pandemic and continued with the rise of far-right movements, as if Europe had grown tired of the hard-won democracy in the East, gained just 30 years earlier. From France to Poland and from Hungary to Germany, many people’s expectations had been disappointed, and the new extremists flagrantly trampled upon the rights of minorities, women, and vulnerable groups. However, they eventually learned, albeit reluctantly after violent protests, that cities must first and foremost be communities: a city without people would not exist.

For a long time, our city had been renowned abroad for its unique dynamism, the opportunities it offered to everyone, the affordability of drinks, and the rich social life. It was like a paradise city, much like Brecht’s Mahagonny, “a place of pleasures where no one works, everyone drinks, plays, fights, and goes to prostitutes; all that matters is whether you can afford the services.”

Tolerance for different opinions and diverse lifestyles, as well as relative social security, declined over time as the city was increasingly mismanaged and temperatures rose. This was reflected in the numbers: after 1992, the illusion no longer held, and the population began to decline towards 1.8 million inhabitants.

The 30 years following the collapse of the totalitarian regime in which I grew up felt like an eternal transition. My generation aged, waiting for something that never happened. Back then, the streets were so crowded every day of the week that you would think no one was working in the office buildings constantly being constructed by real estate developers.

Unexpectedly, in 2020, the pandemic arrived and changed everything. Unfortunately, it is during challenging times and catastrophes that we truly learn and grow, not during easy situations. With each earthquake, fire, and pandemic, people learn to build safer, introduce safety and hygiene standards, and modernize infrastructure, rethinking urban regulations and adapting them to current life, much like they did in the Middle Ages, placing fountains at every important crossroads.

© Ștefan Tuchilă, ultimul Etaj

Slowly, the climate changed everywhere: in Bucharest, the average temperature increased by a few degrees, fueled by continuous traffic congestion and, especially, the “trimming” of trees. Once their cool shade was replaced by air conditioners dripping on the heads of passersby from April to October, making summers harder to bear, Bucharest residents became climate migrants, seeking refuge in the mountains for four months of the year. However, the suffocating flow of cars did not decrease because people understood something, but only after reaching a crisis: frustrated by the continuous traffic jam on the DN road, people from Prahova County started setting fire to large black cars with a “B” license plate. That’s why the Băicoi-Brașov tunnel was dug, and the Pitești-Sibiu highway was finally built, connecting Muntenia with Transylvania.

A city from which anyone can afford to escape the heat becomes semi-deserted for a third of the year – and suffocated by cars for the rest of the time. Many establishments cannot cope with this fluctuating influx and end up closing their doors forever, impoverishing the culinary landscape. You can no longer go to “the Chinese place on Occidentului Street,” “the Frog,” “the Turkish restaurant on Viilor Street,” or “the Russian spot”; you end up ordering everything online. But you didn’t go out to the city just for food, but for entertainment, to meet people. However, people stopped going out too since the pandemic. Along with the disappearance of restaurants, taverns vanish as well, and if you don’t go out anymore, another reason to stay in Bucharest disappears. Then you could stay in another city that offers you more.

Why struggle in a capital city that has been deteriorated by so many incompetent and greedy administrations, with insufficient parking spaces, buildings at risk of collapse, closed or overcrowded nurseries and schools, neglected parks overrun by concerts and festivals that terrorize entire neighborhoods with their decibels? For a while, people worked from home, then they realized that things wouldn’t change anytime soon and that it was preferable to move to a smaller city that, however, functioned better.

Understanding this, those who could, left for Cluj, Iași, or Constanța, where services were cheaper, green areas were closer, and they offered peace and tranquility. What’s the point of a “Green Village” for which you had to cross the city in infernal traffic? You spent hours in the car that you could have spent with your loved ones. And you arrived home completely aggressive – “so many hysterical people in traffic today!” You had become one of them yourself.

In the smaller city, your income might have been slightly lower – but everything was cheaper and more accessible – so practical! Traveling less and more thoughtfully, people brought home lifestyles that no longer fit the “more is more” and “the law is for fools” mentality of the 2010-2020 years. Adversity towards opulence, combined with new sanitary norms, gradually led to profound changes in urban living.

When the pandemic broke out and people were forced to stay in their homes during the first lockdown from March to May 2020, Bucharest residents began to discover their proximity. At that time, I was curating the Street Delivery event, which had been taking place for 15 years on Verona Street, which aimed to transform it into a green, pedestrian axis from east to west. Due to the new regulations, that year the event was divided into islands throughout the city, and its theme was called “ReSolutions.” Projects that proposed the improvement of the space around homes were awarded.

By autumn 2020, some of these small projects had grown, taking root and then being replicated in other neighborhoods. Gradually, flower beds and beehives appeared on the rooftops of many buildings, first around Cișmigiu Park and in the gardens of the Dorobanți neighborhood, then in Pantelimon and Militari – even though we were the only European capital where beekeeping was not encouraged, but explicitly prohibited. This was absurd because urban honey is actually cleaner than “rural” honey since bees can filter out pollutants but not pesticides from the environment. Paradoxically, some of the first guerilla gardeners were actually employees of the Parliament Palace, who had planted a small vegetable garden in its courtyard.

The pandemic in 2020 accelerated some changes that had already been underway for some time. Among them was the reconsideration of urban space. First, malls fell out of use, those large, rare places where people used to cram together – they reminded the population of the consumer frenzy that followed the poverty of the 1980s. In some neighborhoods, there were hardly any commercial spaces at all – that’s where the appearance of pop-up markets was supported, held for two or three days a week, like the one at the University corner where we used to go on Thursdays and Fridays, with you in the stroller and later on bicycles, to buy blackberries, quinces, and cheese.

Sidewalks were widened, and the importance of cars, which had reached a number equal to the population in 2021, diminished. They congested the streets from Monday to Friday and mysteriously disappeared on weekends. The ostentatious and heavy SUVs, which could block multiple parking spaces at once, went out of fashion. They had become status symbols that no one could afford to buy with their salaries. Wasting resources had become the mark of parvenus from bygone times. “Small is the new big,” every child knew by then, and children became more resourceful than their parents and grandparents, preferring experiences over material wealth.

Temporary pedestrianization was introduced: on many streets, car traffic was prohibited in the evenings, which encouraged local businesses in the neighborhoods. Gradually, people finally began to perceive public space as belonging to everyone, not to no one, so tall fences went out of style. A street with 3-meter fences became a road between battlements, not pleasant at all, and it made you wonder, “What important thing do they have to hide here?”

Then, a belt of greenhouses and community gardens grew around the city, which could be rented annually to grow vegetables close to home. Small streets shaded by pines and oaks became trendy again. It was easy to navigate through our city; signs and infographics were placed everywhere in the hope that tourists who once came for cheap drinks would return for the quality of services.

People understood that shade provided coolness, not air conditioners that heated the surroundings and wasted energy. Thus, buildings were equipped with facade blinds and brise soleil. Inspired by the Greek city model, city officials introduced the “Umbrella” program – a cheap solution that turned apartments into greenhouses and standardized facades, instead of the thermal insulation programs that had struggled to take off in the 2010-2020 period.

To decongest the streets and create socializing spaces close to home, ground floors of apartment buildings were transformed into neighborhood shops and parking spaces. Trees were planted on both sides of the streets, and small parks were created at every possible intersection, reclaiming spaces previously occupied by cars. Now you have access to green spaces on every street corner; there’s no need to travel to a park. Seniors and mothers with young children were the first to benefit from these improvements.

With the opening to the Greek city model, suitable for the arid climate of the steppe region where Bucharest is located, other lessons were learned from the Hellenic experience, where the capital clearly set the tone: Athens was already one of the most densely populated cities in Europe, growing from 4,000 inhabitants gathered around historical ruins in 1833 to 3 million in 2020.

To accommodate the wave of Greek immigrants from Asia Minor starting in 1920, the Athenians invented and endlessly replicated throughout the city the “polikatoikia,” a type of building with 4-7 floors and a simple concrete structure, which now represents the overwhelming majority of buildings in Greek cities. The initial constructions adhered to urban planning rules and were pleasant, with sufficiently high ceilings, 100 square meter apartments, and friendly balconies. However, after the 1960s, the quality of construction began to decline in favor of profit.

We hoped not to repeat the mistakes of Athenians: prioritizing the interests of real estate developers, ignoring urban development regulations, which led to the construction of buildings that were too close to each other and “face-to-face.” To make room for them, Athenians had demolished older, classical-style buildings.

But that was already happening here anyway, even in the “restituted” parks, now exploited for real estate purposes. Then, the almost identical reproduction of the same dull building model on every plot of land. The taller, the better! And it should be as cheap as possible! But the apartments themselves were expensive, large, residential, with an average size of 75 square meters, starting from 3 rooms upwards, contradicting the needs of Bucharest residents for smaller and more affordable housing. My generation had already made this mistake.

Only the fetishization of historical substance remained, the principle on which Athens had built its entire modern identity. Due to lack of interest and education, and because of the unclear property situation, Bucharest residents had neglected their heritage for decades – or what was left of it after the communist systematization and demolitions. And now they risked jumping to the opposite extreme, transforming the facades of the 1980s apartment blocks into fake Art Deco.

In essence, Bucharest had much in common with Athens, its older sister in every respect. But it lacked the sea. Our capital had emerged in the midst of the semi-arid Bărăgan Plain, on a fold of land eroded by the Dâmbovița River, as a marketplace at the crossroads of commercial routes between the Levant and Western Europe. The local climate had always been relatively harsh, with temperature extremes, even before the climate crisis, compared to most settlements in the region that were located “below the mountains” or closer to larger, navigable waters.

Over time, the city continued to grow, most significantly during the industrialization period when it tripled in size between 1912-1948, surpassing 1 million inhabitants. Then, it experienced another wave of growth after 1966, with the forced centralization by the communists, reaching over 2 million residents in 1992.

© Ștefan Tuchilă, ultimul Etaj

Like Athens, the city had developed without consistency, without harmony in the mix of architectural styles and forms, many of which contradicted each other from the moment they appeared (such as the traditional Neo-Romanian style with liberal modernism at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries). Growing rapidly and with changing administrations that didn’t manage to complete the projects they started, the city had been hit by various urban plans, all of which were initiated but never fully executed.

Thus, chaos and urban heterogeneity became ingrained here, reflected in the way architectural styles blend and details from “Little Paris” coexist with a little Moscow and a small Istanbul. Each person did as they saw fit, enclosing balconies, personalizing facades, erecting fences where it seemed convenient. It wasn’t until after the pandemic in 2020 that open balconies reappeared, after being used as storage spaces for so long. After all, the balcony is what provides shade to the sidewalks and facade and offers a semi-public space where you can interact with others – and during lockdown, without the risk of infection (at that time, it was called social distancing).

And the river, the ancient Dâmbovița, on whose banks the city was founded, became the absolute center of interest. In a competition organized by the Architects’ Association in 2020, the winning project proposed a series of bridges that moved the action from the city center directly onto the river, transforming the industrial canal-like banks hastily created in the 1980s into genuine sloping gardens.

Water became the essential theme of the capital: swimming pools, recreational areas, and especially drinking fountains are now everywhere! Today, nobody would buy bottled water from a store as we used to. Single-use plastic had become absurd, and the European Union had banned its use since 2019 to protect rivers and seas.

The city’s natural springs, such as Bucureștioara, were rediscovered. In parks, public toilets with water were reintroduced, converted into restaurants after the 1990s. With the new administration elected in 2020, everyone understood what a business private contracts for public toilets had been, inappropriately labeled as “eco.”

When the pandemic hit and people were required to stay at home during the first lockdown from March to May 2020, Bucharest residents began to discover their sense of proximity. At that time, I was curating the Street Delivery event, which had been taking place on Verona Street for 15 years. The event aimed to transform the street into a green pedestrian axis from east to west. However, due to the new regulations, the event that year was divided into islands throughout the city, and its theme was called “ReSolutions.” Projects that focused on improving the spaces around homes were awarded.

By the autumn of 2020, some of these small projects had flourished and started to spread to other neighborhoods. Gradually, rooftops of many buildings became adorned with layers of flowers and beehives, first around Cișmigiu Park and in the gardens of the Dorobanți neighborhood, and later in Pantelimon and Militari. Interestingly, Bucharest was the only European capital where beekeeping was not encouraged; in fact, it was explicitly prohibited. This was absurd because urban honey is actually cleaner than “rural” honey since bees can filter out pollutants but not pesticides from the environment. Paradoxically, some of the first guerilla gardeners were employees of the Parliament Palace, who had planted a small vegetable garden in its courtyard.

The pandemic in 2020 expedited changes that had been brewing for some time. One of these changes was the reconsideration of urban space. Malls, once crowded and reminiscent of the consumer frenzy that followed the poverty of the 1980s, fell out of favor. In some neighborhoods, commercial spaces were scarce. As a result, pop-up markets emerged, operating two or three days a week, such as the one near the University, where I used to go on Thursdays and Fridays with you in the stroller, and later on bicycles, to buy blackberries, quinces, and cheese.

Sidewalks were widened, and the importance of cars, which had reached a number equal to the population in 2021, diminished. They congested the streets from Monday to Friday and mysteriously disappeared on weekends. The ostentatious and heavy SUVs, which could block multiple parking spaces at once, went out of fashion. They had become status symbols that no one could afford to buy with their salaries. Wasting resources had become the mark of parvenus from bygone times. “Small is the new big,” every child knew by then, and children became more resourceful than their parents and grandparents, preferring experiences over material wealth.

Temporary pedestrianization was introduced: on many streets, car traffic was prohibited in the evenings, which encouraged local businesses in the neighborhoods. Gradually, people finally began to perceive public space as belonging to everyone, not to no one, so tall fences went out of style. A street with 3-meter fences became a road between battlements, not pleasant at all, and it made you wonder, “What important thing do they have to hide here?”

Then, a belt of greenhouses and community gardens grew around the city, which could be rented annually to grow vegetables close to home. Small streets shaded by pines and oaks became trendy again. It was easy to navigate through our city; signs and infographics were placed everywhere in the hope that tourists who once came for cheap drinks would return for the quality of services.

People understood that shade provided coolness, not air conditioners that heated the surroundings and wasted energy. Thus, buildings were equipped with facade blinds and brise soleil. Inspired by the Greek city model, city officials introduced the “Umbrella” program – a cheap solution that turned apartments into greenhouses and standardized facades, instead of the thermal insulation programs that had struggled to take off in the 2010-2020 period.

To decongest the streets and create socializing spaces close to home, ground floors of apartment buildings were transformed into neighborhood shops and parking spaces. Trees were planted on both sides of the streets, and small parks were created at every possible intersection, reclaiming spaces previously occupied by cars. Now you have access to green spaces on every street corner; there’s no need to travel to a park. Seniors and mothers with young children were the first to benefit from these improvements.

With the opening to the Greek city model, suitable for the arid climate of the steppe region where Bucharest is located, other lessons were learned from the Hellenic experience, where the capital clearly set the tone: Athens was already one of the most densely populated cities in Europe, growing from 4,000 inhabitants gathered around historical ruins in 1833 to 3 million in 2020.

To accommodate the wave of Greek immigrants from Asia Minor starting in 1920, the Athenians invented and endlessly replicated throughout the city the “polikatoikia,” a type of building with 4-7 floors and a simple concrete structure, which now represents the overwhelming majority of buildings in Greek cities. The initial constructions adhered to urban planning rules and were pleasant, with sufficiently high ceilings, 100 square meter apartments, and friendly balconies. However, after the 1960s, the quality of construction began to decline in favor of profit.

We hoped not to repeat the mistakes of Athenians: prioritizing the interests of real estate developers, ignoring urban development regulations, which led to the construction of buildings that were too close to each other and “face-to-face.” To make room for them, Athenians had demolished older, classical-style buildings.

But that was already happening here anyway, even in the “restituted” parks, now exploited for real estate purposes. Then, the almost identical reproduction of the same dull building model on every plot of land. The taller, the better! And it should be as cheap as possible! But the apartments themselves were expensive, large, residential, with an average size of 75 square meters, starting from 3 rooms upwards, contradicting the needs of Bucharest residents for smaller and more affordable housing. My generation had already made this mistake.

Only the fetishization of historical substance remained, the principle on which Athens had built its entire modern identity. Due to lack of interest and education, and because of the unclear property situation, Bucharest residents had neglected their heritage for decades – or what was left of it after the communist systematization and demolitions. And now they risked jumping to the opposite extreme, transforming the facades of the 1980s apartment blocks into fake Art Deco.

In essence, Bucharest had much in common with Athens, its older sister in every respect. But it lacked the sea. Our capital had emerged in the midst of the semi-arid Bărăgan Plain, on a fold of land eroded by the Dâmbovița River, as a marketplace at the crossroads of commercial routes between the Levant and Western Europe. The local climate had always been relatively harsh, with temperature extremes, even before the climate crisis, compared to most settlements in the region that were located “below the mountains” or closer to larger, navigable waters.

Over time, the city continued to grow, most significantly during the industrialization period when it tripled in size between 1912-1948, surpassing 1 million inhabitants. Then, it experienced another wave of growth after 1966, with the forced centralization by the communists, reaching over 2 million residents in 1992.

Like Athens, the city had developed without consistency, without harmony in the mix of architectural styles and forms, many of which contradicted each other from the moment they appeared (such as the traditional Neo-Romanian style with liberal modernism at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries). Growing rapidly and with changing administrations that didn’t manage to complete the projects they started, the city had been hit by various urban plans, all of which were initiated but never fully executed.

Thus, chaos and urban heterogeneity became ingrained here, reflected in the way architectural styles blend and details from “Little Paris” coexist with a little Moscow and a small Istanbul. Each person did as they saw fit, enclosing balconies, personalizing facades, erecting fences where it seemed convenient. It wasn’t until after the pandemic in 2020 that open balconies reappeared, after being used as storage spaces for so long. After all, the balcony is what provides shade to the sidewalks and facade and offers a semi-public space where you can interact with others – and during lockdown, without the risk of infection (at that time, it was called social distancing).

And the river, the ancient Dâmbovița, on whose banks the city was founded, became the absolute center of interest. In a competition organized by the Architects’ Association in 2020, the winning project proposed a series of bridges that moved the action from the city center directly onto the river, transforming the industrial canal-like banks hastily created in the 1980s into genuine sloping gardens.

Water became the essential theme of the capital: swimming pools, recreational areas, and especially drinking fountains are now everywhere! Today, nobody would buy bottled water from a store as we used to. Single-use plastic had become absurd, and the European Union had banned its use since 2019 to protect rivers and seas.

The city’s natural springs, such as Bucureștioara, were rediscovered. In parks, public toilets with water were reintroduced, converted into restaurants after the 1990s. With the new administration elected in 2020, everyone understood what a business private contracts for public toilets had been, inappropriately labeled as “eco.”

Now, Lake Herăstrău is clean, and regular swimming competitions are held there, culminating in the big April crossing, where 300 people swim from Pescăruș to the elegant pedestrian bridge under the railway overpass.

This is how the reorganization of neighborhoods began: there are no more purely residential neighborhoods like Bercenii or strictly corporate neighborhoods like Pipera, where poor people had to commute daily. Different functions were introduced in all neighborhoods, such as parks, swimming pools, sports arenas, and summer gardens that also serve as open-air cinemas. Flexible part-time work schedules became popular, prioritizing office spaces for families and individuals who cannot work from home.

With great success, after the elections in 2024, the previous sector divisions in the form of a pizza were replaced by 20 metropolitan districts. As smaller administrative units, it became easier for the mayors to take responsibility and address local issues. There are no longer situations like before, where you had the Unirii Square in the heart of the city and the Livezilor Alley in Ferentari in the same sector, with the latter only making the news around election time.

The administration itself has completely changed. Mayors regularly walk the streets during peak hours and in all weather conditions, using public transportation, walking, or cycling, without drivers or security, to monitor the well-being of their city. They have learned that you can’t truly understand the issues of your city if you live outside of it and only traverse it in an SUV with a driver and security, as many did in the early decades of the century.

Moreover, the number of security guards has significantly decreased. The era of snobby secretaries, bodyguards who triage emergency cases, and security guards at pharmacies and grocery stores is long gone. Public service has become a respectable and respectful matter: being a public servant means serving the citizens well, not exercising control or abusing them. When good services are provided, everyone benefits.

Education underwent reform as well. Initially, due to the lack of space resulting from new sanitary regulations (pandemic!), school hours started to be held in museums, greenhouses, parks, gardens, and swimming pools. Seeing the excellent results and the need for additional staff, now with much smaller classes of 10-15 children, the changes continued. In addition to traditional teachers, professionals from different fields started teaching for a few hours a week. Working in the public service is now trendy.

The old school buildings have become community centers, with public spaces for residents, mainly used by young people but also open to seniors, with libraries and multifunctional halls. Regular earthquake response training takes place here: people have learned from the last major earthquake that hope lies in civil society, not the system.

Despite the climatic and administrative complications, or perhaps precisely because of them, Bucharest has grown into a pleasant city with diverse public spaces, realizing its significant potential.

Now let’s see what you will do with it. Good luck!

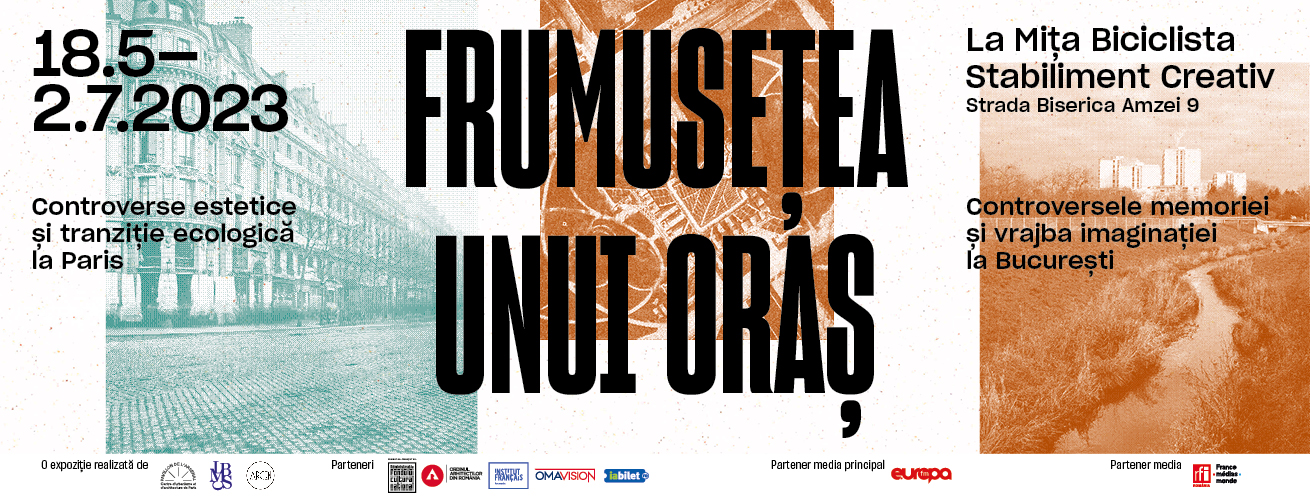

Frumusețea unui oraș. București. Mița Biciclista.

Intre 18.5-2.7.2023 a avut loc o expoziție despre frumusețea Parisului, care marchează primul sezon cultural la Casa Mița Biciclista din piața Amzei. La invitația ARCEN am curatoriat in deschiderea ei o mica expoziție despre frumusețea Bucureștiului.

Link despre expo pe site-ul Zeppelin.

Detalii despre conținut urmează in josul paginii, iar la final gasiti un link catre emisiunea despre Frumusetea Bucurestiului.

Extras din textul curatorial:

DE CE BUCUREȘTI?

Cum e București? Un oraș în mijlocul câmpiei, cu oameni grăbiți. Mereu in șantier, orașul compromisurilor, orașul târguielii, așa a fost mereu, prin natura așezării sale la întretăierea unor vechi rute negustorești între Levant și Apus. Cand întrebi pe cineva de ce s-a hotarat pentru București, îți va spune ca “pentru cineva”. Pentru oamenii sai. Pentru dinamica lor specială.

Cum este București? E orașul care nu-ți mai da drumul. Pleci – și revii mereu.

Ca să înțelegem orașul, îl vom lua pe îndelete, explorand cele șase teme care-l compun.

- Texturile:

Fiecare oraș are texturile sale, imaginile, mirosurile, ceea ce putem atinge, lumina pe care o simțim pe piele.

- Grădinile și verdele:

Cel mai bun moment al orașului este probabil primăvara, cu teii în floare. Sau în septembrie, cu castanele căzând pe trotuar, toamna blândă care durează până târziu în octombrie. Văzut de sus, orașul arată că o grădină zăpăcită. Chiar și în cele mai aride cartiere se zbate verdele. Vara e prea cald și iarna e prea frig.

Dar serile de vară când suntem cu toții pe afară? Sau iarna când zăpadă amuțește în fine toate sunetele traficului și gri-ul.

Dacă ar fi să dorim un singur lucru orașului, e puțină umbră. Și liniștea care vine odată cu umbra.

- Dâmbovița:

Capitala noastră a apărut în mijlocul Bărăganului semiarid, într-un pliu al terenului erodat de Dâmbovița. Clima a fost aici mereu mai aspră, cu extreme termice, dacă e să comparăm cu majoritatea așezărilor din zonă, care se află “sub munte” sau la o apă mai mare, navigabilă. Dâmbovița în sud și salba de lacuri a Colentinei în nord, cu bucureștenii forfotind între cele două. Ar trebui să le purtăm mai multă grijă.

- Moștenirea culturală:

Crescând rapid și cu administrații schimbătoare, care n-au apucat niciodată să termine de realizat proiectele demarate, orașul a fost lovit în timp de diverse sistematizări, toate începute și neduse la bun sfârșit. Așa s-au împământenit haosul, heterogenitatea urbană, reflectate în felul în care se amestecă stilurile arhitecturale și conviețuiesc bucăți care par luate din Paris, Moscova sau Istanbul. Fiecare face aici cum îl taie capul, închide balcoane, personalizează fațade, trage un gard cât mai înalt pe unde i se pare avenit.

Astfel orașul s-a dezvoltat neunitar, deloc armonios în învălmășeala de stiluri și forme – multe din ele contrazicandu-se încă de la apariție (cum ar fi neoromânescul tradițional cu modernismul liberal la final de secol XIX și început de sec. XX).

- Cartierele și identitatea lor:

Cartierele vechi și liniștite, Cotroceni, Icoanei, Armeneasca, cu străzi întortocheate, cu copaci care asigură destulă umbră vara și frâng crivățul iarna, creând un microclimat mai blând, sunt foarte apreciate pentru scara lor umană. Apoi cartierele de blocuri: Balta Alba, Drumul Taberei, Obor, Floreasca, Tei, Pantelimon, Militari, Rahova, Ferentari, Berceni, Calea Moșilor (partea nouă), Vitan, Decebal, Calea Grivitei, Chibrit.

În București exista migrația zilnică nord-sud: mulți dorm în sud, unde densitatea populației e mult mai mare, și lucrează în nord, unde s-au construit birourile. Pleci dimineața dintr-un cartier dormitor ca Bercenii și lucrezi toată ziua într-un cartier-corporatist că Pipera, ca să te întorci seara.

Bucureștenii, mereu în mașini, claxonându-și drumul prin orașul sufocat.

- Ospitalitate / Oameni:

Cum sunt bucureștenii? După vechime, de trei feluri: Localnici, dintotdeauna aici, foarte puțini și liniștiți până la blazare. Orașul lor e cel de sub agitația zilnică, cel în care se plimba când pleacă toți ceilalți. Apoi, cei semi-permanenți, care vin aici “la pomul lăudat” și pleacă în weekend și de sărbători. Ei sunt cei mai mulți – însă ei nu văd decât orașul apăsător și aparent smucit, luni-vineri, ambuteiaje și nervi, pe goană. Apoi musafirii, mereu bineveniți, indiferent de unde vin și ce așteaptă să găsească aici.

Vă invităm să descoperiți urme din toate acestea în expoziție: de la imaginile cu orașul vechi ale lui Alex Gâlmeanu, dar și unele de acum, ale lui Andrei Bîrsan, Alberto Groșescu și ale Anei Vasile, vederi de sus de pe acoperișuri ale lui Ștefan Tuchilă, vestitul accident din piața Amzei al lui Roman Tolici, precum și pictura cu praf din Berceni a lui Nicolae Comănescu, dar și plantele sălbatice ale Irinei Neacșu. Plăcuțele cu poezii ale lui Mugur Grosu. O mică colecție de obiecte care reprezintă Bucureștiul și părțile lui bune, aromele și texturile. O piatră cubică, o coroană de salcie din Dâmbovița. O eugenie și o minge de pe un acoperiș ale lui Zoltan Bela. Coconul lui Dumitru Gorzo. O serie de texte care povestesc orașul, prin ochii câtorva dintre oamenii săi.

Vă invităm să lăsați și voi un rând sau un obiect aici.

Despre expoziție am vorbit si la TVR Cultural în emisiunea “Intrare libera” a lui Marius Constantinescu – ale cărui texte despre grădinile orașului sunt de găsit si pe pereții casei Miței. Ceilalti invitați au fost Edmond Niculușcă, arh. Vera Dobrescu, specialist în peisagistică (via Zoom), Dia Radu și Matei Martin – #IntrareLibera de vineri. Regizori Anca Lazarescu și Micu Aziza.

Masa

Într-o zi o să am în fine masa aia mare la care o să se adune lumea dragă.

În timp au fost câteva mese la care îmi găseam locul.

Masa florentină de la bunica – o masă lungă și aproape neagră, cu desenele mele sub sticlă – cam rece sticla aia – însă se punea fața deasupra, ca un ștergar brodat – aici veneau toți cu povesti, cu frici, cu zâmbete, se întindeau la cafele și dulcețuri – până la urmă se găseau soluții pentru orice. Nu mai e casa aia de o vreme și masa e acum înghesuită într-un apartament.

Masa rotundă cu picior hexagonal de la bunicii din partea mamei, unde mâncai sub privirea blândă și amuzată a străbunicului din tablou. Acolo erau șnițele și preiselbeeren. Și afară la geam atârna o căsuță de păsări făcută de bunicul, mereu asaltată de sticleți gălăgioși.

Masa din parterul întunecos al străbunicii, unde te simțeai mereu ca la jour fixe și stăteai cu spatele drept și ascultai radio și poveștile ei cu zeppeline zburând pe cer, dar și cu morții de la cutremurele și bombardamentele trăite.

Masa alor mei, tot rotundă, luminoasă, odată veselă, însă mereu cumva tensionată și reprezentativă; în ultima vreme doar locul certurilor și al fețelor lungi, peste care se aude constant agitația, “mai vreți supă? vreți o cafea? mai vreți cartofi? aduc prăjitură?”

Parcă nu ne mai auzim demult.

Masa din garsoniera mea de la final de facultate, unde se adunau aproape zilnic prieteni – unii nu mâncau porc, alta era vegetariană, se dezbăteau aici toate subiectele pământului, jucam jocul ăla cu “cine sunt eu?” cu bilețele în frunte. Cel mai bine era că aici se rezolvau probleme și conflicte, ziceau ei. Era loc pentru toți. Eu cică găteam constant pe margine, cu un pahar de roșu într-o mâna și cu pauze de țigară la fereastră.

A fost o vreme masa din Zürich, care sâmbăta era mereu plină cu bunătăți și câteva ziare pe care le aduceam când veneam de la cai, indiferent de vreme. Pe la 11 când se trezea și el, pe mine deja ma lua somnul. Pe după masă veneau prietenii, găteam, poveștile lor se împleteau cu vinul roșu și ultimele idei de proiecte și expoziții.

Nu a fost să fie masa din apartamentul amenajat cu atâta drag în Mântuleasa. Mare, albă, mereu plină – dar venită într-un moment în care nu mai eram noi – eram deja fiecare pentru el.

Acum masa mea e mică, încăpem maxim doi și-o pisică.

Într-o bună zi o să am masa mea mare, cu copii și cu prieteni în jur,

unde se poate așeza oricine vine cu drag și fără țâfnă.

București cotidian. Viața în 7 cartiere, 2020

București cotidian. Viața în 7 cartiere, 2020, era o serie de emisiuni care explorau viața de zi cu zi în diverse cartiere ale Bucureștiului. Această serie a luat naștere în contextul izolării în timpul pandemiei și a schimbării temei inițiale către urgența climatică. Pe durata lunilor de izolare, oamenii au petrecut mult timp acasă și au fost limitați în deplasarea în zonele cunoscute din centrul orașului. Astfel, s-a evidențiat importanța îmbunătățirii vieții cotidiene la nivel de proximitate, în cartierele orașului.

Emisiunile explorează diferite cartiere și aduc în prim-plan nevoile specifice ale acestora. Dezbaterile implică specialiști din diverse domenii, cum ar fi sociologi, strategi, urbanisti, dar și persoane care trăiesc în aceste cartiere. Fiecare emisiune este ghidată de un riveran local, care oferă informații și perspectiva sa asupra zonei respective.

Printre cartierele abordate se numără

Icoanei, (Centrul și centrele),

Cișmigiu și Poezia Vecinătăților,

Uranus Rahova – Înapoi în viitor,

Kiseleff 1 Mai, Parc și Muzee,

Grivița Giulești – Ateliere și cinematografe, și

Vatra Luminoasă – Cartier 2.0.

Scopul emisiunilor este de a evidenția nevoile și potențialul fiecărui cartier, de a promova implicarea comunității și de a contribui la dezvoltarea urbană durabilă și la îmbunătățirea calității vieții în toate cartierele orașului București.

Această serie de emisiuni a facut parte din evenimentul Street Delivery București, organizat de Fundația Cărturești și Ordinul Arhitecților din România, susținută prin proiectul strategic al OAR finanțat prin #TimbrulDeArhitectură.

“Din Cotroceni în Ferentari și din Titan în Dorobanți, fiecare cartier are nevoi, are locuri “bune” și “rele”, are oamenii săi. Explorăm, împreună cu 3 invitați pricepuți din diferite domenii – strateg, psihiatră, brancardier, avocată, sociolog, croitoreasă, stylist, urbanistă, taximetrist. La fiecare cartier, ne îndrumă un riveran.”

Ce vrem:

- Un oraș mai plăcut în toate cartierele, nu mutarea centrului de greutate într-o zona care funcționează acum. Vrem să funcționeze fiecare cartier, să trăiești bine în el, să fie siguranță, sănătate, cultură peste tot, nu doar in centru si 100% susținut din bugetul de stat.

- Vrem walkability, un oraș in care sa te plimbi cu drag, nu pietonalizare, care e in sine o capcana, omorând magazinele și, odată cu ele, fluxul de pietoni.

- Politici publice, program oficial susținut de primărie. Odată cu molima nu trece și urgența. Vrem siguranță publică și sănătate publică. Designul e doar un instrument.

Siguranță, confort, sănătate publică, cultură – nu se exclud, ci se sprijină reciproc. Direcția de azi e inevitabila. Covid doar a accelerat ceva care oricum trebuia să se întâmple. - Dialogul cu societatea civila. De salutat că primăria a început sa asculte de organizații ale societății civile, OAR demult luptă pt îmbunătățirea calității vieții urbane, ideea e bună, dar alegerea zonelor încă nu e ideala și riscă să genereze o opoziție vehementă-> Cum facem ca inițiativa bună să fie susținută de o dorința legitimă a locuitorilor?

- Planul de mobilitate. Calmarea traficului, reducerea, nu desființarea lui: aprovizionarea și riveranii sunt tot trafic. În weekend centrul e chiar plăcut. Doar în weekend însă, ar fi deci păcat să li se ia tocmai asta. Iar traficul principal e generat dimineata de miscarea dinspre cartierele-dormitor din sud catre zona de birouri din nord.

Cartea Bucuresti Sud.

Interviu “Orașul Posibil”

Între sistem şi bobor

Negocierea spaţiului public în Bucureşti, Articol în Zeppelin, Octombrie 2017

Bucuresti 2057

Un text despre București din 2057, când fiul meu va avea vârsta mea de acum.

Toate fotografiile sunt realizate de Stefan Tuchila in cadrul proiectului Ultimul Etaj.

Dragul meu,

Ai câștigat alegerile… Felicitări! Să fie într-un ceas bun.

Cumva însă ne așteptam. De când erai mic mă întrebam cum ar fi sa ajungi într-o zi în fruntea acestui oraș pe care l-am iubit atât, l-am părăsit apoi și l-am regăsit mult mai târziu: haotic, dinamic, chinuitor.

În fond, semnele se arătau de pe-atunci. Într-o dimineață de vară ne-ai zis “Azi sunt primar! Poftiți la mine în birou” și ne-ai invitat în capătul balconului, în pampers și cu un tricou roșu, hotărât. Am râs noi, dar parcă se potrivea. Aveai doi ani jumate, stăteam încă pe Splai, în “blocul cu zei”, prin fața căruia Dâmbovița curgea tristă într-un canal cu pereți de beton.

Acum ai vârsta pe care o aveam eu atunci. S-au schimbat multe între timp. Mă întreb ce schimbări o să aduci tu.

***

Se știe că viitorul e în densificarea locuirii, adică în orașe, desigur. Până la urmă traiul urban e cel mai eficient, drumurile-s scurte și diversitatea e proporțională cu dimensiunea: cu cât e orașul mai mare, cu atât oferă mai multe șanse tuturor: divertisment, cultură, locuri de muncă, educație.

De aici vine magnetismul orașelor mari. Un oraș mare își poate permite o varietate de localuri, grădină botanică, universitate, operă și un transport în comun excelent. Sub 1 milion de locuitori nu se poate vorbi de metrou, o investiție scumpă, pentru care e nevoie de o masă critică de utilizatori. Cu cât e folosit de mai mulți, transportul în comun devine mai rentabil. Cel mai bun exemplu e tramvaiul, tradițional mijloc de transport electric: cu cât îl folosesc mai puțini, devine mai scump de întreținut și mai neglijat. Dacă scădem sub un anumit prag, nu ni-l mai putem permite, și ajungem să mergem toți cu mașinile personale.

Se spune că orașul e un organism eficient, însă asta e valabil doar atâta timp cât e administrat corect. Orice sistem administrat prost duce la neîncredere în autoritate, corupție, instabilitate politică și în final la scădere economică, la sărăcie. E un cerc vicios, se creează sectoare de populație vulnerabile, care depind mai mult de administrație și ajung mai expuse abuzurilor.

Într-un asemenea context nu e de mirare că nivelul de agresivitate crește proporțional cu complicațiile la care e supus cetățeanul pentru a obține servicii de bază. De aceea majoritatea orașelor din top 10 în statisticile cu calitatea vieții sunt din Elveția și Germania, iar București se află tradițional în jumătatea inferioară a clasamentului.

Pe primul loc concurează de ani buni Viena cu Zürich, orașe în care te orientezi ușor, în care cetățenii au încredere în edili, care la rândul lor îi tratează cu respect și îi ascultă: sunt exemple de bună guvernare. Aceasta este de obicei participativă: locuitorii cartierelor iau parte la deciziile și la bunul mers al orașului împreună cu profesioniștii, iar administrația ia hotărâri în mod transparent. În București grupurile de inițiativă civică au apărut în urma unor conflicte de interes între primării și cetățeni începând cu 2010.

***

La ultimul cutremur mare, în 2027, tu aveai 10 ani. Administrația ratase monumental să facă față dezastrului, crescând enorm numărul victimelor, așa cum se întâmplase și la incendiul din Colectiv, în 2015, doi ani înainte sa te naști, când muriseră mai mulți oameni în spitale decât în incendiul propriu-zis. De atunci înainte bucureștenii au învățat și societatea civilă s-a organizat mai bine, implicându-se în operaţiuni de pregătire pentru molime și reacție în caz de seism.

Anii 2020 au fost un deceniu agitat: a început cu pandemia Covid-19 și a continuat cu mișcările de extremă dreapta, de parcă Europa se săturase de democrația cu greu câștigată în Est cu 30 de ani mai devreme: din Franța până în Polonia și din Ungaria până în Germania, așteptările multora fuseseră dezamăgite, și noii extremiști călcau senin în picioare drepturile minorităților, femeilor și categoriilor vulnerabile. Însă au învățat apoi, cu greu, după demonstrații violente, că oraşele trebuie să fie în primul rând comunități: un oraş fără oameni nu ar exista.

Multă vreme orașul nostru fusese renumit peste hotare pentru dinamica sa deosebită, șansele pe care le oferea tuturor, pentru ieftinătatea băuturii și viața socială bogată. Un fel de paradise city, ca Mahagonny al lui Brecht, „un loc al plăcerilor, în care nimeni nu lucrează, toată lumea bea, joacă, se ceartă și merge la prostituate, tot ceea ce contează este dacă îți poți permite serviciile.”

Toleranța la opinii, stilurile de viață diverse și relativa siguranța socială au scăzut în timp, pe măsură ce orașul a fost administrat din ce în ce mai prost și a devenit mai cald. Asta s-a reflectat în cifre: după 1992 mirajul nu a mai ținut și populația a început să scadă spre 1,8 milioane de locuitori.

Cei 30 de ani care au urmat prăbușirii regimului totalitar în care am crescut eu au însemnat o tranziție devenită parcă eternă. Generația mea a îmbătrânit așteptând ceva care nu se mai întâmpla. Pe atunci, străzile erau atât de pline în orice zi a săptămânii, încât ai fi zis că nu lucra nimeni în birourile pe care le tot construiau dezvoltatorii imobiliari.

În 2020 a venit pe neașteptate pandemia care a schimbat totul. Din păcate, tocmai greul și catastrofele ne învață, nu creștem din situațiile ușoare. Cu fiecare cutremur, incendiu și pandemie, oamenii învață să construiască mai sigur, introduc norme de securitate și igienă și modernizează dotările edilitare, regândind regulamentele urbane și adaptându-le la viața actuală, cum au făcut în evul mediu, amplasând fântâni la fiecare răspântie mai importantă.

Încet, clima s-a schimbat peste tot: în București, temperatura medie a crescut cu câteva grade, care au fost susținute de ambuteiajul continuu și mai ales de “toaletarea” copacilor. Odată înlocuită umbra lor răcoroasă cu aere condiționate care picură în capetele trecătorilor din aprilie până în octombrie, făcând verile mai greu de suportat.

Bucureștenii au devenit migranți climatici, refugiați către munți vreme de câte patru luni pe an. Însă fluxul sufocant de mașini nu s-a redus pentru că ar fi înțeles lumea ceva, ci abia după ce s-a ajuns la o criză: exasperați de ambuteiajul continuu de pe DN, prahovenii se apucaseră să incendieze mașinile mari și negre cu număr “B”.

De aceea s-a săpat atunci tunelul Băicoi – Brașov și s-a făcut în fine autostrada Pitești – Sibiu, care unește Muntenia cu Transilvania.

Un oraș din care oricine își poate permite să fugă de caniculă ajunge semi-părăsit o treime din an – și sufocat de mașini în restul timpului. Multe localuri nu pot face față acestui flux variabil și ajung să-și închidă porțile pentru totdeauna, sărăcind peisajul culinar. Nu mai poți merge „“la chinezul de pe Occidentului”, „“la Frog”, „“la turcul de pe Viilor”, „“la ruși”, ajungi să comanzi totul online. Dar nu pentru mâncare ieșeai în oraș, ci pentru divertisment, ca să te vezi cu lumea. Care însă nu mai ieșea nici ea de când cu pandemia. Odată cu restaurantele dispar și cârciumile și dacă nu mai ieși, mai dispare un motiv pentru a sta în București. Atunci ai putea sta și în alt oraș, care-ți oferă mai mult.

De ce să te chinui într-o capitală pusă pe butuci de atâtea administrații incompetente și hrăpărețe, cu locuri de parcare insuficiente, clădiri cu risc seismic, creșe și școli închise sau suprasolicitate, parcuri neîngrijite și cotropite de concerte și festivaluri care terorizează cu decibelii lor cartiere întregi? O vreme lumea a mai lucrat de acasă, apoi a realizat că lucrurile nu se vor schimba prea curând și că e preferabil să se mute într-un oraș mai mic, care funcționează însă mai bine.

Înțelegând asta, cine a putut, a plecat atunci la Cluj, la Iași sau la Constanța, unde serviciile erau mai ieftine, zonele verzi mai aproape și-ți dădeau liniștea. La ce bun un „Green Village” pentru care trebuia să traversezi orașul în traficul infernal? Petreceai în mașină ore pe care le-ai fi putut petrece cu cei dragi. Și ajungeai acasă complet agresiv – „câți isterici erau azi în trafic!” Ajunsesei chiar tu unul dintre ei..

În orașul mai mic și venitul tău era poate puțin mai mic – dar totul era mai ieftin și la îndemână – atât de practic!

Călătorind mai puțin și mai chibzuit, lumea a adus acasă modele de viață care nu se mai potriveau cu “more is more” și „“legea e pentru fraieri” ale anilor 2010-20. Adversitatea față de opulență, combinată cu noile norme sanitare au dus în timp la schimbări profunde ale locuirii în oraș.

***

Când izbucnise pandemia și au fost obligați să stea în case la primul lockdown, martie – iunie 2020, bucureștenii au început să-și descopere proximitatea. Pe atunci făceam curatoriat pentru evenimentul Street Delivery, care se întâmpla de 15 ani mereu pe strada Verona, pe care își propusese să o transforme în axă verde, pietonală, de la est la vest. Ca urmare a noilor reglementări, în acel an evenimentul a fost spart în insule prin tot orașul și tema lui s-a numit ReSoluții. Au fost atunci premiate proiecte care propuneau îmbunătățirea spațiului din preajma casei.

Pâna în toamna 2020, unele din aceste mici proiecte au crescut, prinzând rădăcini și au început să fie reproduse apoi în alte cartiere. Treptat pe acoperișurile multor blocuri au apărut straturi de flori și stupi, întâi pe cele din jurul Cișmigiului și în grădinile din cartierul Dorobanți, apoi în Pantelimon și Militari – deși eram pe atunci singura capitală europeană în care apicultura nu era încurajată, ci chiar explicit interzisă. Ceea ce este absurd, pentru că mierea „de oraș” e chiar mai curată decât cea „de țară” pentru că albinele pot filtra noxele, dar nu pesticidele din mediu. În mod paradoxal, printre primii guerilla gardeners au fost chiar dintre angajații Palatului Parlamentului, care plantaseră o mică grădină de zarzavat chiar în curtea acestuia.

Pandemia din 2020 a grăbit unele schimbări care începuseră de ceva vreme. Printre ele a fost regândirea spațiului urban. Întai au ieșit din uz mall-urile, mari, rare, în care se înghesuiau odată oamenii – ele oricum aminteau populației de isteria consumului ce a urmat sărăciei din anii 1980. În unele cartiere lipseau pe atunci spațiile comerciale aproape de tot – acolo a fost susținută apariția piețelor volante, două-trei zile pe săptămână, cum era deja cea de pe colțul Universității, unde mergeam joia și vinerea cu tine-n cărucior și mai târziu pe bicicletă, să luam mure, gutui și telemea.

S-au lărgit trotuarele, a scăzut importanța mașinilor, care ajunseseră să egaleze numărul de locuitori în 2021, înfundând străzile de luni până vineri și dispărând misterios în weekend. Au ieșit în fine din modă SUV-urile lătărețe și greoaie, care își permiteau să blocheze mai multe locuri de parcare deodată, status simboluri pe care nimeni nu și-ar fi permis să și le cumpere din salarii.

Irosirea resurselor în sine a devenit marca parveniților din vremuri apuse. Small is the new big, știa de-acum orice copil, iar copiii au devenit mai chibzuiți decât părinții și bunicii lor, preferând experiențele în locul averilor.

S-a introdus pietonalizarea temporară: pe multe străzi se interzice circulația mașinilor pe timpul serii, ceea ce a încurajat localurile din cartiere.

Încet, lumea a început să perceapă în fine spațiul public ca fiind al tuturor, nu al nimănui, așa că s-au demodat și gardurile înalte. O stradă cu garduri de 3 metri devine un drum între metereze, nu e plăcută și te face să te întrebi “Ce au aici așa important de ascuns?

Apoi în jurul orașului a crescut o centură de sere și grădini comunitare pe care le poți închiria anual, pentru a crește legume aproape de casă. Au revenit în vogă străzile mici, umbrite de pini și stejari. E ușor să te orientezi prin orașul nostru, au fost puse indicatoare și infografice peste tot, în speranța că se vor întoarce acum pentru calitatea serviciilor turiștii care veneau odată pentru… băutura ieftină.

Lumea a înțeles că răcoarea e asigurată în primul rând de umbră, nu de aere condiționate care încălzesc în jur și costă aiurea. Astfel au fost dotate clădirile cu jaluzele pe fațadă și brise soleil.

Inspirați de modelul orașelor grecești, edilii au introdus programul „Umbra” – o soluție ieftină și care transforma apartamentele în sere și uniformiza fațadele, în locul programelor de anvelopare termică cu care se chinuiseră prin 2010-20.

Pentru a descongestiona străzile și a crea spații de socializare aproape de casă, parterurile blocurilor au fost transformate în magazine de cartier și în locuri de parcare. S-a început plantarea arborilor pe ambele părți ale străzilor și la orice intersecție posibilă s-au făcut parcuri mici în locurile eliberate de mașini. Acum ai acces la spații verzi pe orice colț de stradă, nu mai e nevoie să călătorești până la un parc. Seniorii și mamele cu copii mici au fost primii care au profitat de aceste îmbunătățiri.

Odată cu deschiderea pentru modelul grecesc de oraș, potrivit climei aride, de stepă de aici, s-au introdus și alte învățăminte din experiența elenă, unde evident tonul fusese dat de capitală: Atena era pe atunci oricum unul din cele mai dense orașe din Europa, după ce crescuse în mai puțin de două sute de ani de la 4000 de locuitori, adunați ca într-un sat mai mare în jurul ruinelor istorice la 1833, la 3 milioane în 2020.

Pentru a putea primi valul de imigranți greci veniți din Asia Mică începând cu 1920, atenienii inventaseră și reproduceau la nesfârșit în orice cartier polikatoikia, un tip de imobil de 4-7 etaje, cu structură simplă, de beton, care reprezintă între timp majoritatea covârșitoare a construcțiilor din orașele grecești. Cele construite inițial respectau regulile de urbanism și erau plăcute, cu tavane suficient de înalte, cu apartamente de 100m2 și balcoane prietenoase, însă după anii 1960 calitatea construcțiilor a început sa scadă în favoarea profitului.

Ne gândeam noi atunci măcar să nu repetăm greșelile atenienilor: prioritizarea intereselor dezvoltatorilor imobiliari, cu ignorarea regulilor de dezvoltare urbană, care au dus la construirea unor blocuri mult prea aproape unele de altele și “față în față”. Pentru a le face loc, atenienii își demolaseră clădirile mai vechi, clasiciste.

Dar asta se întâmpla deja oricum la noi, până și în parcurile “retrocedate” și exploatate imobiliar. Apoi, reproducerea aproape identică a aceluiași model anost de clădire pe orice teren. Cât mai înaltă! Și cât mai ieftină să fie! Dar cu apartamente scumpe, mari, rezidențiale, cu o medie de 75m2, de la 3 camere în sus, contrazicând nevoia bucureștenilor de apartamente mici și mai accesibile. Pe acestea, generația mea le greșise deja.

Rămăsese doar fetișizarea substanței istorice, principiul pe care Atena își construise întreaga identitate modernă. Din lipsă de interes și de educație și din cauza situației neclare a proprietății, bucureștenii își neglijaseră timp de decenii patrimoniul – sau ce rămăsese din el după sistematizarea și demolările comuniste. Asta mai lipsea, să sară acum în extrema opusă, transformand în Art Deco fals fațadele de bloc din anii 1980.

În fond, București avea multe în comun cu Atena, sora lui mai mare din toate punctele de vedere.

Însă marea îi lipsea. Capitala noastră apăruse în mijlocul Bărăganului semiarid, într-un pliu al terenului erodat de Dâmbovița, ca târg la răscrucea unor rute comerciale între Levant și Europa de Vest. Clima de aici fusese mereu relativ aspră, cu extreme termice, chiar și înainte de criza climatică, dacă e să comparăm cu majoritatea așezărilor din zonă, care se aflau “sub munte” sau la o apă mai mare, navigabilă.

În timp, orașul a tot crescut, cel mai mult în timpul industrializării, și s-a triplat între 1912-1948, depășind 1 milion de locuitori, apoi într-un nou val după 1966, cu centralizarea forțată de comuniști, ca să ajungă la peste 2 milioane în 1992.

Ca în Atena, orașul se dezvoltase fără consistență, deloc armonios în învălmășeala de stiluri și forme, multe din ele care se contraziceau încă de când apăruseră (cum ar fi neoromânescul tradițional cu modernismul liberal la final de secol XIX și început de sec. XX). Crescând rapid și cu administrații schimbătoare, care nu apucau să termine de realizat proiectele începute, orașul fusese lovit de diverse sistematizări, toate începute și neduse la bun sfârșit.

Așa s-au împământenit aici haosul, heterogenitatea urbană, reflectate în felul în care se amestecă stilurile arhitecturale și conviețuiesc detalii din micul Paris cu o mică Moscova și cu un mic Istanbul. Fiecare făcea ce credea de cuviință, închidea balcoane, personaliza fațada, trăgea un gard pe unde i se părea mai avenit. Abia după pandemia din 2020 au reapărut balcoanele deschise, după ce fuseseră atâta timp folosite ca spații de depozitare. În fond, balconul este cel ce ține umbra trotuarelor și fațadei și oferă un spațiu semi public, în care poți interacționa cu alții și pe timp de lockdown, fără riscul de a te molipsi (distanțare socială îi spuneau pe atunci).

Iar râul, batrâna Dâmbovița, pe firul căreia se întemeiase odată orașul, a devenit centrul de interes absolut. La un concurs organizat de Ordinul Arhitecților în 2020, proiectul câștigător a propus o serie de poduri care mutau acțiunea din centrul orașului direct PE râu, schimbând malurile cu aspect de canal industrial, făcute la iuțeală în anii 1980, în veritabile grădini în pantă.

Apa a devenit tema esențială a capitalei: sunt acum peste tot bazine de înot, ștranduri și, mai ales, fântâni cu apă potabilă! Nimeni nu ar mai cumpăra astăzi PETuri cu apă de la magazin, ca pe vremea mea. Plasticul de unică folosință ajunsese oricum o absurditate și Uniunea Europeană a interzis folosirea lui începând din 2019 pentru a proteja râurile și mările.

S-au redescoperit izvoarele naturale ale orașului, ca Bucureștioara. În parcuri s-a revenit la WC-uri publice cu apă, convertite în restaurante după anii 1990. Odată cu noua administrație aleasă în 2020, toată lumea a înțeles ce biznis fuseseră contractele private pentru WC-uri publice, nepotrivit numite “eco.”

Acum lacul Herăstrău e curat, se organizează aici regulat întreceri de înot, culminând cu marea traversare din Aprilie, la care 300 de oameni înoată de la Pescăruș până la elegantul pod pietonal de sub pasajul de cale ferată.

S-a văzut că de fapt nu densitatea în sine deranjează, ci calitatea designului urban din zonele densificate. Marele deal interzis pe care se aflau Palatul Parlamentului și Catedrala Mântuirii Neamului, înconjurate de un zid și păzite de jandarmi, a fost deschis publicului în 2025 și parțial convertit în cartier high rise. Pe locul unde fusese odată băgat în pământ stadionul Republicii și complet distrus cartierul Uranus, s-a construit baza sportiva cu același nume, cu bazinele de înot și arena deschisă, cum era odată renumitul ștrand Kiseleff unde mergeam când eram mică la cursuri.

Cartierele vechi și liniștite, cu străzi întortocheate, cu copaci care asigură destulă umbră vara și frâng crivățul iarna, creând un microclimat mai blând, sunt foarte apreciatepentru scara lor umană.

Dacă apar aici câteva blocuri P+14, contrazicând reteaua urbană mărunta, infrastructura nu face față și colapsează: cu blocuri făcute rapid pe bani puțini, fără design și cât mai înalte, printre case mai mici și elegante, care s-au păstrat în timp, canalizarea devine insuficientă, trotuarele și parcurile se transformă într-o mare parcare, străzile înguste neputând prelua atâta trafic. Avantajul de a locui într-o casă urâtă este că pe a ta nu o vezi din afară. Însă dacă în jur încep să apară multe asemenea blocuri, densitatea cartierului depășește posibilitățile acestuia și oamenii încep să se certe pe locurile de parcare, spațiul verde dispare sub mașini, piețele sunt sacrificate pentru a fi înlocuite cu baruri cool, unde vin oameni să petreacă mai ales sâmbătă seara, dar spațiul public ramane mort în restul săptămânii. Astfel, calitatea vieții urbane scade în zonă, anulând motivul investiției dezvoltatorului.

În timp s-a văzut că merită respectate reglementările urbane și densitățile stabilite în PUZ-uri.

În restul orașului se merge acum pe conversia spațiilor existente. Miile de birouri goale se transformă treptat în apartamente șic, mall-urile au devenit centre comunitare, iar vechile spații industriale și clădirile de patrimoniu sunt restaurate în cadrul unui program susținut de primărie. Pentru a fi apoi reactivate cu funcțiuni diferite.

În primă instanță s-a început cu un program de scutire de taxe pe două decenii pentru cei care investeau în salvarea patrimoniului. Aceasta e o operațiune costisitoare, întrucât prevede atât consolidarea structurii, cât și refacerea detaliilor. Însă dacă sunt reproduse peste tot aceleași clădiri mari cu arhitectura anonimă, repetată în orice climă și relief și lipsită de istorie vie, orașul devine anonim – puțini ar vrea sa meargă ca turiști la Pyongyang pentru arhitectura apăsătoare cu detalii care se repetă la nesfârșit, care îți urlă în față că nu există individualism și că sistemul e mai tare decât oricine.

Pe măsură ce structurile de patrimoniu au reintrat în circuit, primăria a restaurat și refuncționalizat o parte din ele, începând cu parking Ciclop de la 1923, o parcare istorică în mijlocul orașului și hanul Solacolu, devenit centru cultural după expropriere, în jurul căruia s-a reactivat toata zona căii Moșilor Vechi, unde erau odată atelierele și manufacturile meșteșugarilor.

Așa a început și reorganizarea cartierelor: nu mai există cartier dormitor ca Bercenii sau cartier- corporatist ca Pipera, între care să facă bieții oameni naveta zilnic. S-au introdus funcțiuni diferite în toate cartierele, sunt parcuri, stranduri și arene de sport, grădini de vară – cinema. Și se poartă locurile de muncă part-time cu program de lucru decalat, mai liber, birourile fiind prioritizate pentru familiști și persoane care nu pot lucra acasă.

Cu mare succes, după alegerile din 2024 s-au introdus cele 20 de districte metropolitane în locul sectoarelor în forma de pizza. Fiind unități administrative mai mici, edililor le e mai ușor să răspundă de ele, să știe problemele, nu mai sunt situații ca înainte, unde aveai în același sector piața Unirii din buricu’ târgului și aleea Livezilor din Ferentari, din care cea din urmă apărea la știri doar în preajma alegerilor.

Administrația în sine s-a schimbat complet. Edilii se plimbă regulat pe străzi, la oră de vârf și pe orice vreme, cu transportul în comun, pe jos sau cu bicicleta, fără șofer și fără pază, ca să urmărească bunul mers al lucrurilor din orașul lor, pentru că au învățat că nu poți ști cu adevărat care sunt problemele orașului tău dacă locuiești în afara lui și-l traversezi doar la bordul unui SUV cu șofer și pază, cum făcuseră cei mai mulți în primele decenii ale secolului.

Oricum, numărul paznicilor a scăzut enorm. Vremurile cu secretare țâfnoase, bodyguard care face triajul la Urgență, pază la farmacie și la magazinele alimentare au apus demult.

Serviciul public a ajuns o chestiune respectabilă și respectuoasă: nu ești bugetar ca să stăpânești sau abuzezi cetățenii, ci ca să-i servești. Cu servicii bune, toată lumea profită.

A fost apoi reforma educației. Întâi din cauza lipsei de spațiu rezultate în urma noilor norme sanitare (pandemia!), orele de școală au început să se țină în muzee, în sere, în parcuri și grădini, și în bazine de înot. Văzându-se rezultatele excelente și fiind nevoie de suplimentarea personalului, acum cu clase mult mai mici, de 10-15 copii, schimbările au continuat: pe lângă profesorii clasici au început să predea profesioniști din domenii diferite, măcar câteva ore pe săptămână. A devenit la modă să lucrezi în serviciul public.

Vechile clădiri ale școlilor sunt acum centre comunitare, cu spații publice pentru riverani, folosite mai ales de oameni tineri, însă deschise și seniorilor, cu biblioteci și săli multifuncționale. Regulat se fac aici antrenamente pentru reacția în caz de seism: lumea a ținut minte de la ultimul mare cutremur că speranța e în societatea civilă, nu în sistem.

Cu toate complicațiile climatice și administrative – sau poate tocmai din cauza lor – București a devenit un oraș plăcut, cu spații publice diverse. Pentru care aveam de fapt mare potențial.

Să vedem ce o să faci tu acum din el. Succes!

Dorothee Hasnaș, arhitect și manager cultural, a fost curator Street Delivery 201 5-2021 din partea Ordinului Arhitecților din România. A moderat “București Cotidian”, o emisiune live despre viața în cartierele capitalei, unde invitații au fost riveranii cartierelor și specialiști din diverse domenii caracteristice respectivei zone. Printre proiectele editoriale sale se numara forturi.ro, uranusacum.ro, maicugoldstein.ro si artaferoneriei.ro.