Preluat de pe site-ul OAR – https://oar.archi/timbrul-de-arhitectura/de-vorba-in-biblioteca/

Constanța arhitectului Haim Goldstein (Horia Maicu): Salvarea, uitarea şi din nou salvarea lui Maicu

Arhitectul Horia Maicu, născut Haim (Harry) Goldstein, a reintrat în actualitate după salvarea spectaculoasă a arhivei sale dintr-un tomberon de pe strada Batiștei de către pictorul Daniel Balint, care trecea pe acolo întâmplător în ianuarie 2012. Mulţi au luat atunci pentru prima dată contact cu cel care a fost arhitectul-șef al Capitalei între 1958 și 1968 și care și-a pus semnătura pe o serie de clădiri-simbol ale Bucureștiului – Combinatul Poligrafic „Casa Scânteii” (astăzi Casa Presei Libere), Teatrul Naţional, Sala Palatului, mausoleul din Parcul Carol etc.

În bena de gunoi de pe strada Batiștei, de lângă faimosul „bloc roșu”, proiectat chiar de Horia Maicu și unde arhitectul avea un apartament, s-a găsit arhiva personală a acestuia ‒ arhivă care aduna atât faimoasele sale edificii bucureștene, cât și o altă lume, cea a debutului său în arhitectură, în orașul său natal, Constanța. Horia Maicu a locuit în „blocul roșu” pe strada Batiştei, în Bucureşti, până la moartea sa, în 1975, iar în 2012, noii proprietari nu au înțeles valoarea arhivei aceluia care fusese arhitectul-şef al Capitalei în perioada lui Gheorghiu-Dej și au aruncat-o alături de moloz, haine şi bucăţi de mobilă.

Salvarea, uitarea şi din nou salvarea

Vreme de câţiva ani, recuperarea de la gunoi a arhivei lui Horia Maicu nu a prezentat mare interes. Abia în 2015 a fost organizată o expoziție în foaierul Teatrului Național din București și, în acest moment, publicul larg l-a descoperit/redescoperit pe Horia Maicu și a aflat istoria arhivei sale. A curs ceva cerneală în perioadă, apoi s-a așternut din nou liniştea.

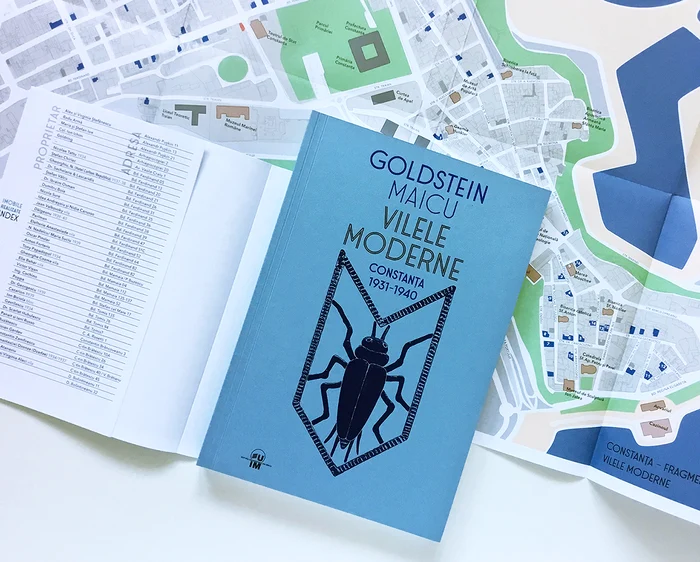

În 2022, un grup de specialiști sub coordonarea arh. Dorothee Hasnaș a reluat cercetarea cu privire la fostul arhitect-șef al Capitalei. Perioada abordată în cercetare, finalizată cu lucrarea Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931-1940, este cea a debutului lui Horia Maicu, pe atunci Haim Goldstein, în lumea arhitecturii. Descoperirile sunt fabuloase: peste 100 de imobile ridicate în 10 ani, o amprentă unică păstrată în feronerie și detaliile imobilelor și niciun strop de realism-socialist în lucrările sale. De asemenea, cercetătorii au descoperit că arhiva salvată în 2012 era volantă și au făcut toate demersurile ca aceasta să ajungă în administrarea unei instituții care să fie capabilă să o ofere publicului pentru consultare.

Astăzi, arhiva Goldstein-Maicu este în administrarea Ordinului Arhitecţilor din România, iar numele salvatorului, pictorul Daniel Balint, se află la loc de cinste.

Constanţa se modernizează

La începutul celei de-a doua jumătăți a secolului al XIX-lea, Constanța se află încă la marginea Imperiului Otoman. Orașul din epocă e un port mic, vechi și cosmopolit, cu arhitectură preponderent rurală.

Într-un fel, orice oraș-port este definit de mare: el nu funcționează la fel în toate direcțiile, ca un oraș de șes, ci se orientează cu totul către mare, ca un amfiteatru. Este, prin definiție, un oraș deschis, care intră în contact cu diferite culturi și influențe, prin traficul maritim.

Neschimbată de veacuri, relativ liniștită, zona trece la sfârșitul secolului al XIX-lea printr-un un război cumplit, în care câștigă teritorii și se afirmă cu un rol nou, intrând într-o perioadă cu adevărat specială.

Schimbarea la faţă

Pentru orice modernist, orașul Constanța datorează enorm Regelui Carol I. După Războiul de Independență și Pacea de la Berlin, din 1880, România dobândește, în urma unui schimb de teritorii, Dobrogea, un teritoriu eterogen din punct de vedere al populației și religiilor. Un ordin al primăriei referitor la aplicarea legii stării civile, din 28 decembrie 1878, menționează bisericile greacă, bulgară, catolică și templul așkenazilor (1). De asemenea, recensământul din 1880 arată că orașul Constanța avea doar 5.204 locuitori (2), paisprezece ani mai târziu, numărul se dublase (3), iar în 1904 ajunsese deja la 13.385 de locuitori (4), pentru ca, după Primul Război Mondial, în 1928, să numere 40.933 de locuitori (5).

Totuși, pentru proaspătul rege, Dobrogea reprezenta acel teritoriu de care avea mare nevoie în dorința sa de a dezvolta și a moderniza tânărul stat român. Cele trei județe din sudul Basarabiei (Cahul, Ismail și Bolgrad) reprezentau o ieșire la Marea Neagră, dar una dificil de administrat. Crearea unui port de anvergura Hamburgului, din Germania natală, așa cum își dorea Carol I, era imposibilă în acest spațiu, însă Constanța îndeplinea toate criteriile. Singurul mare obstacol era traversarea Dunării.

Construirea podului de la Cernavodă de către inginerul Angel Saligny, între 1890 și 1895, a adus un și mai mare avânt în dezvoltarea celui mai mare oraș-port al țării. De altfel, la data de 16 octombrie 1896, Regele Carol I, într-o ceremonie fastuoasă, punea piatra de temelie a construirii Portului Constanța (6).

Deși orașul reprezenta un punct comercial și turistic, pe linia vestitului tren Orient Express, administrația regală românească a oferit Constanţei, la finele secolului al XIX-lea și începutul secolului XX, un impuls extraordinar în dezvoltarea sa. Înființarea Serviciului Maritim Român (1887), dar și dezvoltarea unor clădiri publice-simbol ‒ palatul comunal (care a avut chiar două sedii: prima clădire, inaugurată în 1896, este azi Muzeul de Artă Populară, cea de-a doua clădire, din Piața Ovidiu, a fost inaugurată în 1921), palatul administrativ, palatul de justiție, palatul episcopal, teatrul, muzeul, biblioteca, spitalul și, bineînțeles, Cazinoul (1905-1910) ‒ au schimbat fundamental fața orașului.

Hoteluri şi locuinţe private luxoase

Construcțiile administrative au fost secondate de investiții private. Astfel, remarcăm apariția unor locuințe private luxoase și impunătoare precum: palatul Sturdza (autorizație obținută în 18897), locuințele lui Amédée Alléon, Vila Sutzu (1898-1899), Casa Hrisicos (1903), Casa Pariano (sfârşit de secol XIX), Casa Petre Grigorescu (sfârşit de secol XIX), Casa cu lei (1895), Casa Manissalian (1905) etc. Citind mărturiile de epocă și corelându-le cu informațiile statistice, observăm o întreagă elită care se formează din oameni pregătiți, de care noul oraș are mare nevoie.

De asemenea, de la cele câteva cârciumi și hanuri, după 1880, apar numeroase hoteluri: Hotel d’Angleterre, Hotel Gabetta, Hotel Ovidiu, Hotel de France, Hotel Metropol, Hotel Carol I, Hotel Palace, Hotel Europe Elite, Hotel Mercur, gata să asigure servicii de la cele mai simple la cele mai rafinate gusturi.

Se schimbă şi modul de a călători

Constanța interbelică continuă să fie un punct de atracție pentru călători și un nod comercial deosebit, însă apar tot felul de elemente de modernitate. Încet-încet, birjarii fac loc automobilelor, iar călătoriile cu avionul nu mai sunt ceva exotic. În 1934, şapte avioane au efectuat curse pe ruta București – Constanța – Balcic – București. Cursele aeriene deveniseră și ele regulate, e drept, pentru elita care își petrecea vacanțele la Balcic și pe întreaga Coastă de Argint.

Încă din 1920, pe strada D.A. Sturdza (azi Revoluției), într-o clădire foarte frumoasă, Casa Embiricos, își deschidea birourile compania transatlantică American New East & Black Sea Line – linie regulată, rapidă și directă Constanța – New York. „Pe parcursul voiajului se pun la dispoziția celor interesați și în funcție de tarif mâncare, muzică, cinematograf și baie”8.

În anii ’30, Serviciul Maritim Român avea aici 14 nave de pasageri care efectuau curse în întreaga lume. Poate o parte dintre acestea au fost surse de inspirație pentru tânărul Haim Goldstein în dezvoltarea stilului său modern, asemănător cu imaginea unui pachebot. Rutele cele mai importante erau: Constanța – Varna – Istanbul – Salonic; Constanța – Istanbul – Pireu – Alexandria; Constanța – Istanbul – Pireu – Beyrouth – Haifa etc.

Blocul Kalambotos din Constanţa, imobil realizat în 1934 în stil modernist

Cazinoul

Dincolo de băile de soare, care îndemnau pe toți să ajungă în sezonul estival pe plajele amenajate la Constanța, principala atracţie a urbei a fost, începând din anul 1910, evident, Cazinoul Comunal, monumentalul edificiu construit de către arhitectul Daniel Renard, în stilul Art Nouveau.

Locul unde se făceau sau se pierdeau averi, la ruletă, la bacara sau la alte jocuri de noroc celebre la acea vreme în lumea întreagă. Bineînţeles, Cazinoul Comunal însemna mai mult decât atât: era şi centrul cultural al oraşului, loc de spectacole, expoziţii şi numeroase alte evenimente, dar şi, graţie falezei sale, locul ideal pentru promenadă.

Aceasta este, în câteva tuşe, Constanţa în care a trăit şi activat Haim Goldstein…

Tânărul arhitect Haim Goldstein şi locul său în Constanța interbelică

În 1905, în Constanţa, în casa din strada Libertății nr. 21, se naște Haim ‒ fiul Clarei Herscovici și al cârciumarului Marcu Goldstein. Douăzeci de ani mai târziu, tânărul absolvă liceul și pleacă în Italia, la Roma, cu o bursă de studii. În 1930, revine în orașul natal cu diplome în inginerie și arhitectură şi demarează o seamă de șantiere în antrepriză cu alți arhitecți.

Un element interesant este şi evoluția comunității etnice a arhitectului. Pentru că Haim (Harry) Goldstein este evreu, putem urmări, în traseul său, şi evoluția comunității așkenazilor. Astfel, la momentul intrării Dobrogei în Regatul României, aceasta număra vreo 234 de suflete, în preajma nașterii lui Haim, 1.059, iar în ajunul întoarcerii sale în Constanța de la Roma, 1.050.

Peste 100 de imobile în zece ani

Într-un interval de numai zece ani, între 1931 și 1940, arhitectul participă la construirea a peste 100 de imobile. Astăzi le numim „vile”, deși multe erau, de fapt, „apartment houses”, Blockhaus-uri, imobile P+3 sau 4, cu câte două apartamente pe etaj, un gen de construcție tipică perioadei. Arealul intervențiilor lui Goldstein se extinde peste marginile Constanței, incluzând lucrări în Mamaia, Techirghiol, Eforie, Palazu Mare, poate chiar Silistra.

Multe din aceste imobile se găsesc încă pe străzile Constanței, nevăzute și neștiute, modificate în chip nefericit sau pur și simplu ascunse privirii. Sunt necunoscute, pentru că nu s-a vorbit de ele până acum. Multe au fost descoperite, de altfel, în timpul cercetării arhivei Goldstein, în colecția impresionantă de schițe găsite în pubela din centrul Capitalei.

Schițele făceau odată parte din viața arhitectului Horia Maicu, care nu doar că a participat la proiectarea Combinatului „Casa Scânteii” (1953-1959), ajungând director la Institutul de Proiectare a Construcțiilor și apoi arhitect-șef al Capitalei între 1958 și 1969, dar a şi predat la Institutul de Arhitectură „Ion Mincu” începând cu 1950, locuind într-un apartament dintr-un bloc proiectat chiar de el, pe strada Batiștei nr. 11, împreună cu soția, Sultana, până în anul morții, 1975.

„Ce frumos e desenată fațada”. Tăcere…

În anii aceştia, Haim Goldstein e Horia Maicu, cel care a întors complet spatele perioadei sale constănțene. Cât de mult se detașase de trecutul său rezultă dintr-o anecdotă povestită de arhitectul Romeo Belea, care a lucrat cu el timp de şaptesprezece ani. Mergând odată la Constanța, Belea remarcă o casă de pe bulevardul Ferdinand și spune: „Ce frumos e desenată fațada”. Maicu se oprește și nu spune nimic, doar se uită lung. Era unul din imobilele Goldstein.

Dar, în acele vremuri, Maicu era doar Maicu, în Constanța se construiau blocuri socialiste și Cazinoul ajunsese un local de alimentație publică.

După anii ’50, România trăiește un nou boom imobiliar, declanșat de industrializarea forțată și de determinarea noului regim de a crea noduri industriale, cel dintâi fiind în jurul Capitalei.

După oprirea șantierelor comuniste, la finele lui 1989, România trece printr-o perioadă de somn al Cenușăresei și ajunge astăzi din nou la o nemaipomenită hărnicie imobiliară: de această dată însă, imobilele care nu sunt demolate sunt desfigurate cu intervenții ieftine, care rașchetează detaliile atent construite în anii ’30 și le înlocuiesc cu ready-mades barbare. Hublourile, antenele, artropodele de pe uși nu se mai pot apăra de intervențiile nefaste ale gospodarilor porniți să le înnoiască ‒ citește: înlocuiască ‒ cu orice preț. Lumea de azi nu le mai știe valoarea, prețuind noul, fără a ști să discearnă calitatea.

Lecţiile arhivei Maicu

Arhiva schițelor lui Maicu, găsită în tomberon, păstrată timp de un deceniu de pasionați, a ajuns, în fine, în biblioteca Filialei București a Ordinului Arhitecților din România în toamna lui 2022: a venit momentul oportun ca ea să ne deschidă ochii asupra migalei cu care arhitectul trata pe atunci rezolvarea partiruilor și a fațadei, propunând variante multiple, dar și ca să ne vorbească de o vreme când arhitectul era puternic, beneficiarul îi respecta rolul și constructorul îi urma întocmai planurile. Altceva ar fi fost pe atunci de neconceput.

Acest stop-cadru asupra perioadei constănțene a lui Haim Goldstein (Horia Maicu), prea puțin cunoscută astăzi, ne oferă o sumedenie de imagini: cum era orașul-port atunci, cum s-a dezvoltat, cine își putea permite o vilă semnată Goldstein, cum se explică Modernitatea și Modernismul, prea des confundate cu Art Deco și Bauhaus.

Calambotos, Askitopoulos, Xenakis și Hurmuziadi (greci), Russo, Solaris, Dalla și Cochino (italieni), Goldfeld și Heilpern (evrei), Nedelcu și Huhulescu (români), Calpagioglu și Cuimudoglu (turci) s-au numărat printre comanditarii imobilelor semnate de Goldstein. Mulți dintre ei antreprenori, legați deopotrivă de mare și de uscat și, mai ales, de orașul-port. Sunt oameni înstăriți, care își doresc noutatea, dar respectă standardele și valorile arhitecturale. De aceea, multe dintre imobilele păstrate atrag privirile turiștilor, cu uimire față de splendida construcție, dar și cu indignare la nepăsarea cu care sunt tratate azi.

Cum recunoaștem o casă din repertoriul Goldstein? Invitaţie la descoperire

Majoritatea imobilelor ridicate în Constanța interbelică de către Haim Goldstein se înscriu în stilurile „pachebot” modernist sau imobil cu iz mediteraneean. Există și unele excepții, iar volumul recent publicat, Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931-1940, dedică un capitol generos acestui subiect. Cartea include şi un capitol intitulat Vocabularul Goldstein, în care sunt prezentate forme și detalii arhitecturale, de la intrarea telescopică cu uși împodobite de insecte prietenoase și harnice (greierele, păianjenul, furnica și albina) până la ferestrele cu săgeata și soarele.

Pentru că imobilele au aproape o sută de ani, cititorul îşi va pune poate întrebarea: cum le putem renova, fără să pierdem din valoarea imobilului interbelic? Aceste aspecte sunt și ele surprinse într-un Ghid de bune practici, către finalul cărții.

Dar volumul Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931-1940 propune şi un traseu (pe care îl redăm alăturat) în care veți putea descoperi pe teren imobilele Goldstein care au supravieţuit vremii, cu proporțiile lor zvelte și detaliile lor jucăușe, feroneria delicată a gardurilor, gângăniile pe ușile vilelor moderniste odată atât de însorite, la care intrarea și casa scării joacă rolul principal. Să privim prin ochii întredeschiși ce a rămas din ele astăzi, cu speranța că respectul pentru detalii va renaște înainte ca ele să dispară pentru totdeauna.

Mai multe găsiți online pe maicugoldstein.ro.

Articolul „O descoperire estivală: Constanța arhitectului Haim Goldstein (Horia Maicu)”, a fost publicat în numărul 260 al revistei „Historia”, disponibil la toate punctele de distribuție a presei, în perioada 15 septembrie – 14 octombrie, și în format digital pe platforma paydemic. (revista:260)

Ausstellung 3x Bukarest: Bohème – Diktatur – Umbruch

Die EinladungDie Ausstellung ereignete sich zwischen 26.02.-26.03.2010 in Zürich und fand gleich grossen Anklang: viele Rumänen kamen, um sich zu erinnern, viele andere Besucher, neugierig, etwas über einen Teil Ostblockgeschichte zu erfahren. BILDER AUS DER AUSSTELLUNG HIER

Die EinladungDie Ausstellung ereignete sich zwischen 26.02.-26.03.2010 in Zürich und fand gleich grossen Anklang: viele Rumänen kamen, um sich zu erinnern, viele andere Besucher, neugierig, etwas über einen Teil Ostblockgeschichte zu erfahren. BILDER AUS DER AUSSTELLUNG HIER

Bei Nachfrage könnte man die Ausstellung auch an anderen Orten aufbauen. Für weitere Details und Fragen erreichen Sie mich hier per Mail.

Meine Lieben

Zehn Jahre ist es her, seit ich „für ein Jahr ins Ausland“ ging. Ich bin immer noch weg – aber diese Stadt wird mich nie loslassen. Ich liebe sie, ihre vielen Schichten, ihr ewiges Treiben, die Art, sich immer wieder neu zu erfinden und doch nichts vollständig umzusetzen. Klein Paris – und gleichzeitig klein Istanbul. Sogar klein Moskau, je nach Blickwinkel.

Bukarest folgt mir überall hin.

Ich lade Euch herzlich zur Ausstellung, die vom Leben in Bukarest im Wandel der Zeit erzählt, ein. An der Bar trinkt man rumänischen Wein.

Diese Ausstellung wurde aus eigenen Mitteln finanziert. Sie ist verkaufs- und eintrittsfrei. Für einen symbolischen Beitrag steht ein dankbares Gefäss an der Bar.

Ich freue mich auf Euer Kommen!

So begann die Ausstellung in der Nachtgalerie, in dreieinhalb Räumen im Untergeschoss eines Hauses in Zürich. Die Einrichtung entspricht jeweils dem Ambiente des Raumes, in welchem man in den unterschiedlichen Perioden zusammenkam: heute – die Bar, früher – der Salon, zwischen den Zeiten – im Korridor der Platte.

Der Eingang ist hinterm Haus, die Treppe runter, an der Garderobe vorbei. Die erste Tür links führt zur Bar in “unsere Zeit”.

An der Bar unterhält man sich in drei Sprachen

Von dort aus geht man in den Salon über – die Bohème vor dem zweiten Weltkrieg. Damals wie heute gab es in Bukarest eine grosse Toleranz für unterschiedlichste Baustile. Die Stadtväter wollten nur das Beste für ihre Stadt – und jedem sein Bestes sah anders aus. Es wurden klare städtebauliche Richtlinien beschlossen, diese jedoch immer nur für begrenzte Zeit umgesetzt. Jedes Mandat brachte neue Richtlinien mit sich. Man genoss das Leben in vollen Zügen, ungeachtet der Verhältnisse, als gäb’s kein morgen.

Der Salon © Irina Vencu

Der Salon © Irina Vencu

Um in den nächsten Teil der Ausstellung zu kommen -zur Diktatur- muss man die Galerie verlassen und hinter der Ecke den zehn Meter langen Korridor finden, welcher nirgendwohin führte.

Das rasende Tempo der erzwungenen Industrialisierung bringt Zuzügler in die Stadt, durch diese verdreifacht sich die Bevölkerung innert wenigen Jahren. Das neue Regime möchte Bukarest völlig umgestalten, nichts soll mehr an das alte, aristokratische Leben erinnern. Die neue Gestalt tritt allmählich durch breite Achsen, rasch gebaute Plattenviertel und Eintönigkeit in Erscheinung.

Versammeln in öffentlichen Räumen ist ab sofort verpöhnt. Um miteinander zu kommunizieren treffen sich die Leute in den Treppenhäusern und Korridoren der Plattenbauten. Dort wird auch Propaganda gemacht, Plakate zeigen wie man “richtig” lebt, wohnt und sich anzieht.

Die Fotos aus diesem Bereich sind aus den 50er Jahren, als die Bauten noch neu waren und über einen gewissen Reiz verfügten.

Der Korridor

Rechts sind die Wohnungstüren, hinter welchen eine jeweils unterschiedliche Geräuschkulisse zu hören ist: ein Ausschnitt vom XIII-ten kommunistischen Parteitag, Radio Freies Europa mit Aussagen der Flüchtlinge in Paris, in der Tagesschau wird die Produktion pro Hektar gelobt, Radio Beromünster berichtet über den Einzug der sowjetischen Panzer in Ungarn…

Zwischen den Wohnungen 36 und 37 fehlt eine Tür. Hier ist eine verlassene Wohnung, die Möbel in der Mitte gestapelt. Aus den Fenstern sieht man auf die Abrissarbeiten der 80er Jahre, eine Strasse, die zwei Tage später aufhörte zu existieren, das Kloster Vacaresti, welches ein halbes Jahr nach sorgfältiger Restaurierung niedergerissen wurde. Im Hintergrund sieht man den Volkspalast im Bau, seitlich deutet ein weisses Fenster darauf hin, dass die Zukunft, von dieser Zeit aus gesehen, unbekannt ist. Ein Stövchen mit Kochplatte und Kerzen wartet auf seinen Einsatz, falls wieder mal unerwartet der Strom, die Heizung, das Wasser abgestellt werden…

Die verlassene Wohnung

Die verlassene Wohnung

Detailierte Artikel über die einzelnen Teile der Ausstellung folgen in Kürze.

Grundriss Galerie

Grundriss Galerie

Expo 3x Bucuresti: Boema – Dictatura – Tranzitie

Aceasta expozitie a avut loc in Zürich in perioada 26.02.-26.03.2010 si a beneficiat de un mare succes: multi romani au venit sa-si aminteasca cu drag – si multi straini au vizitat-o, curiosi sa afle cate ceva despre Europa de est.

La cerere, expozitia ar putea fi adaptata si prezentata din nou in alt spatiu.

Pentru mai multe detalii si intrebari sunt disponibila pe adresa de mail.

Februarie 2010.  Invitatia.

Invitatia.

Dragii mei

Au trecut zece ani de cand am plecat “pentru un an in strainatate”. Sunt in continuare plecata – insa acest oras nu o sa-mi dea drumul niciodata. Il iubesc, cu straturile lui multe, cu agitatia continua, cu felul sau de a se reinventa mereu, fara a duce totusi nimic pana la capat. Micul Paris -si in acelasi timp micul Istanbul. Chiar si mica Moscova, in functie de perspectiva.

Bucurestii ma urmaresc peste tot.

Vă invit cu drag la o expoziție care povestește despre București în schimbarea vremurilor. La bar găsiți vin românesc.

Aceasta expoziție a fost finanțată prin mijloace proprii. Pe tejgheaua barului se găsește un vas pentru donații.

Ma bucur de oaspeti!

Plan galerie

Plan galerie

Asa a inceput expozitia, in trei incaperi si jumatate, in subsolul unei cladiri din Zürich. 3 incaperi, amenajate dupa locul in care se aduna lumea in perioada respectiva: azi – barul, pe vremuri – salonul, si – intre vremuri – holul de bloc.

Intrarea prin fundu’ curtii pe o scara, pe langa garderoba. Prima usa la stanga este barul din “vremea noastra”.

La bar se discuta in trei limbi

La bar se discuta in trei limbi

De acolo se trece în salonul ce înfățișează boema dinainte de al doilea război mondial. Atunci, că și acum, exista o mare toleranta pentru stiluri arhitectonice foarte diferite. Edilii vroiau binele orașului – și binele fiecăruia arata altfel. Se construia în toate chipurile și se luau decizii urbanistice clare, dar pentru perioade finite. Fiecare mandat nou aducea cu sine legi noi. Și se trăia din plin, cu buzunare pline sau mai puțin pline, de parca nu ar mai veni ziua de mâine.

Salonul © Irina Vencu

Salonul © Irina Vencu

Din expoziție trebuia să ieși din nou pentru a ajunge în cea de-a treia perioadă, cea comunista: un hol de bloc, lung de zece metri, care nu duce nicăieri.

Pentru prima oara în istoria Bucurestilor se vă construi după linii generale care urmează să transforme consecvent întreg orașul, dandu-i o fata cu totul noua și uniforma. În noile blocuri se aduna lumea pe hol și pe scara blocului, ce devin locuri publice, spatiile de întălnire și comunicare. Acolo se făcea și propaganda, cu afișe ce arata cum să locuiești, cum să arați și cum să trăiești corect.

Fotografiile provin din anii ’50, când construcțiile erau noi și aveau încă un oarecare farmec.

Holul de bloc

Pe dreapta, ușile apartamentelor, de după care se aud diferite culise sonore, Radio Europa Liberă, discursurile de la al XIII-lea Congres al Partidului, Telejurnalul lăudând producția la hectar, Radio Beromünster informând despre intrarea tancurilor sovietice în Ungaria…

Intre apartamentele 36 și 37, o ușă lipsește. Înăuntru, spațiul unui apartament părăsit, cu mobila grămadă în mijloc. Pe doua geamuri se văd demolările în curs ale anilor ’80, strada Bateriilor și Mănăstirea Văcărești. În geamul din capăt răsăre Casa Poporului, în construcție. Lateral, un geam alb reprezintă viitorul neclar al orașului și al României în general în acel moment. Reșoul cu plita electrică deasupra – și lumânări, mereu la îndemâna, pentru cazul în care se oprește căldură, apa sau gazele. Anii `80…

Apartamentul părăsit

Apartamentul părăsit

De aici lumea se întoarce la locul preferat de întălnire azi: barul. Vizitatorii încep dezbateri înfocate la un pahar de vin, căutând rezolvări și creând scenarii pentru orașul lor iubit sau pe care au început să-l cunoască și să-l îndrăgească din această seară.

Articolele detaliate despre cele trei părți ale expoziției vor urma în curând.

Visby, die vergessene Hansestadt

Visby am Meer auf halbem Weg zwischen Schweden und Lettland

alle Fotos Wikimedia Commons ©CC

die alten arabischen, römischen & co. Münzen –

Vikinger, gingen in alle Welt – nordische Götter, späte Konvertierung zum Christentum.

St. Olof, kannonisierter König der Norweger

Paralellreligionen und -rituale. Petrus de Dacia. Hugin und Munin, Odin und Frigg, Slepinir mit acht Beinen

die Pferde auf der Insel

12, 13.Jh die Blütezeit. Die Visbianer stärken ihre Beziehungen zu Händlerfamilien aus anderen mächtigen Städten durch das gegenseitigen Verheiraten der Töchter.

Gotländische Genossenschaft

Ab dem 12. Jahrhundert wurde der Ostseeraum im Rahmen der Ostsiedlung zunehmend für den deutschen Handel erschlossen.

In Lübeck entstand nach dem Vorbild kaufmännischer Schutzgemeinschaften die Gemeinschaft der deutschen Gotlandfahrer, auch Gotländische Genossenschaft genannt. Sie war ein Zusammenschluss einzelner Kaufleute niederdeutscher Herkunft, niederdeutscher Rechtsgewohnheiten und ähnlicher Handelsinteressen u.a. aus dem Nordwesten Deutschlands, von Lübeckern und aus neuen Stadtgründungen an der Ostsee.

Der Handel in der Ostsee wurde zunächst von Skandinaviern dominiert, wobei die Insel Gotland als Zentrum und „Drehscheibe“ fungierte. Mit der gegenseitigen Versicherung von Handelsprivilegien deutscher und gotländischer Kaufleute unter Lothar III. begannen deutsche Kaufleute den Handel mit Gotland (daher „Gotlandfahrer“). Bald folgten die deutschen Händler den gotländischen Kaufleuten auch in deren angestammte Handelsziele an der Ostseeküste und vor allem nach Russland nach, was zu blutigen Auseinandersetzungen in Visby, durch den stetigen deutschen Zuzug mittlerweile mit großer deutscher Gemeinde, zwischen deutschen und gotländischen Händlern führte. Dieser Streit wurde 1161 durch die Vermittlung Heinrichs des Löwen beigelegt und die gegenseitigen Handelsprivilegien im Artlenburger Privileg neu beschworen, was in der älteren Forschung als die „Geburt“ der Gotländischen Genossenschaft angesehen wurde. Hier von einer „Geburt“ zu sprechen verkennt jedoch die bereits existierenden Strukturen.

Visby blieb zunächst die Drehscheibe des Ostseehandels mit einer Hauptverbindung nach Lübeck, geriet aber, die Rolle als Schutzmacht der deutschen Russland-Kaufleute betreffend, mit Lübeck zunehmend in Konflikt. Visby gründete um 1200 in Nowgorod den Peterhof, nachdem die Bedingungen im skandinavischen Gotenhof, in dem die Gotländer zunächst die deutschen Händler aufnahmen, für die Deutschen nicht mehr ausreichten.

Der rasante Aufstieg, die Sicherung zahlreicher Privilegien und die Verbreitung der nahezu omnipräsenten Kaufleute der Gotländischen Genossenschaft in der Ostsee, aber auch in der Nordsee, in England und Flandern (dort übrigens in Konkurrenz zu den alten Handelsbeziehungen der rheinischen Hansekaufleute) führte in der historischen Forschung dazu, in dieser Gruppierung den Kern der frühen Hanse zu sehen (Dollinger sieht im Jahr 1161 sogar die eigentliche Geburtsstunde der Hanse überhaupt). Eine Identifizierung der Gotländischen Genossenschaft als „die“ frühe Hanse, täte jedoch allen niederdeutschen Handelsbeziehungen unrecht, die nicht unter dem Siegel der Genossenschaft stattfanden.

St. Olof wurde nach dem verlassen lange als Steinbruch benutzt, nur der Westturm blieb als Ruine übrig.

Lange Zeit Zwischenhalt aller durchreisenden Schiffe, dadurch bessere Handelsbeziehungen zu anderen Ländern als zum übrigen Umland. Daher die grosse Stadtmauer! Siehe auch: Waldemar IV. Atterdag König der Dänen greift an. Gotland wehrt sich tapfer, Visby hält sich komplett aus der Schlacht heraus. Die Gotländer verlieren, Valdemar und seine Armee steht vor den Toren. Die Visbianer machen auf und bereiten sich für Verhandlungen. Valdemar stellt drei grosse Bierfässer auf den Marktplatz auf und verlangt, dass diese bis zum Sonnenuntergang bis zum Rande mit Gold und Silber gefüllt werden, sonst wird die Stadt in Schutt und Asche gelegt und ihre Bewohner geknechtet, ihre Frauen entehrt und ihre Läden geplündert. Beim Anbruch der Nacht sind die Fässer voll, alle Bewohner haben ihre Wertsachen abgegeben, Valdemar geht und lässt Visby seine erkaufte Freiheit.

der Bürgerkrieg mit dem Umland. Tiefe Steuern der Farmen: ca. 12g Silber pro Jahr statt 94 g wie im der Region um den Mälarensee

Häuser gegen den Hafen sind meist Handelshäuser mit mehrstöckigen Lagerräumen, “Verkaufsetage”

“Zinnenfassade” Ausgeklügeltes Latrinensystem.

Paris hatte zur Zeit bereits 100’000 Leute, Visby als Stadt auf einer Insel 6- 7’000.

Die Schiffe werden mit der Zeit grösser und sind nicht mehr gezwungen, in Gotland anzuhalten. Daher beginnt Visby an Bedeutung zu verlieren, die Geschäfte gehen nicht gut und die Verhandelsposition ist geschwächt. Zweite Hälfte des 14. Jh ist eine Sschlechte Zeit für Visby: Bürgerkrieg mit Umland?, Pest suchen die stolze Stadt heim.

1525 Die Armee der Lübecker greift von Norden auf Land an, die Tochter eines Goldschmieds verrät die Stadt und öffnet ein Tor, aus Liebe zu einem ?Offizier. Alle 18 Katedralen werden zerstört und angezündet, allein Marienkirche, da Kirche der Deutschen, bleibt verschont.

Visby erholte sich nie mehr, daher wurden die Kirchen weder wiederaufgebaut, noch für wichtigere Bauwerke als Steinbrüche genutzt.

Einige waren bereits angeschlagen. Die Reformation brachte die katholische Kirche in eine schwächere Rolle, ab 1530 leerten sich die Klöster und alle Kirchen bis auf St. Marien wurden aufgegeben.

Diejenigen Kirchen, die nicht schon als ausgebrannte Ruinen leerstanden,verloren schnell ihre Türen, Fenster und Dächer. Damit war der Weg für den fortgesetzten Verfall geebnet. Die aufgegebenen Kirchen gingen in den Besitz des Hospitals von Visby über, das Einnahmen durch das Verpachten der Ruinen und der dazugehörigen Grundstücke innerhalb und ausserhalb der Stadt erzielte. In gewissem Umfang wurden die Ruinen als Steinbrüche genutzt.

1805 kamen die Ruinen unter Denkmalschutz, erst 50 Jahre später begann man etwas man etwas gegen den weiteren Verfall zu unternehmen.

Die aufgegebenen Kirchen

Grösstes Schiffsunglück vor der Küste – Begräbnis von xy. Sturm.

Das Kasino in Constanta, 1910 – 2005

Das Gründerzeitkasino an der Hafenpromenade ist das Wahrzeichen von Constanţa. Erbaut wurde es 1909 in französischem Neobarockstil von dem rumänischen Architekten Daniel Renard. 1985 wurde es restauriert. In dem prächtigen Gebäude kann man auch schlemmen, der Glücksspielbetrieb aber wurde 2005 eingestellt.

Constanţa ist die älteste Stadt auf rumänischem Boden. Erstmals im Jahre 657 vor Chr. erwähnt, als an der Stelle der heutigen Halbinsel (unter dem heutigen Wasserspiegel, auf dem Platz des heutigen Kasinos) eine griechische Kolonie namens Tomis gegründet wurde. Die Ortschaft wurde 71 vor Chr. von den Römern erobert und in Constantiana umgenannt, zu Ehren der Schwester des Kaisers Constantin des Grossen.

Im Laufe des 13. Jh. wird das Grosse Meer (wie damals das Schwarze Meer genannt wurde) von italienischen Händlern aus Genua dominiert; diese bauten die Stadt aus. Bis 1420 gehört Constanţa zur Walachei und dann schließlich zum Osmanischen Reich, bis es 1878 im Rahmen des Berliner Kongresses mit der Dobrudscha (dessen Zentrum Constanţa ist) Rumänien zugeschlagen wurde.

Unter osmanischer Besetzung bis auf die Grösse eines Dorfes zurück geschrumpft, das von griechischen Fischern und tatarischen Pferde- und Schafzüchtern bewohnt wurde. Die Ortschaft entwickelte sich wieder zur Stadt nach dem Bau der Eisenbahnlinie Cernavodă-Constanţa und des Hafens, in 1865, über den hauptsächlich rumänisches Getreides exportiert wurde. Nach dem Russisch-Türkischen Krieg (1877-1878) gewann Rumänien die Dobrudscha zurück. Constanţa wuchs zum wichtigste Hafen des Landes, was es heute noch ist.

Heutzutage ist der Hafen Constanţa der grösste am Schwarzen Meer und der viertgrösste in Europa. In den nächsten Jahren besteht das Potential, dass Marseille und Antwerpen überholt werden und Constanta an zweiter Stelle hinter Rotterdam landet.

1889, kurze Zeit nachdem die Stadt unter rumänische Verwaltung gekommen ist, wird am Ende des einzigen Boulevards der Stadt, neben dem Genuesischen Leuchtturm, mit dem Bau eines ersten Amüsierlokals begonnen. Das Gebäude des Kasino-Kursaals ist sehr schlicht – aussen mit Holzlatten beschlagen – und beherbergt zwei Tanzsäle, zwei Lesesäle und zwei Spielhallen. Die Terrasse davor, welche sich grösszügig zum Meer hin öffnet, ist der beliebteste Treffpunkt der Stadt. Seeleute, Reisenden und die lokale Elite kommen her, während der Saison finden fast jeden Abend Bälle statt. Zu den Klängen des Militärorchesters wird Walzer getanzt; die Berühmtheiten jener Zeit geben oft Konzerte, die von der Stadtverwaltung finanziert werden.

Constanta zu Beginn des 20.Jh, die Grosse Moschee Carol I, erbaut 1910

Constanta zu Beginn des 20.Jh, die Grosse Moschee Carol I, erbaut 1910

1891 zerstört ein wütender Sturm ein Grossteil des Holzgebäudes. Der Bürgermeister beschliesst ein neues, solideres Gebäude bauen zu lassen, da die Reparatur des alten nicht rentabel wäre.

Das neue Gebäude des «Kursaals» wird 1893 einige Meter weiter vom Genuesischen Leuchtturm entfernt als das alte gebaut, etwa auf der Stelle des heutigen Kasinos. Erneut wird ein schlichter Bau auf Holzstützen im Meer errichtet. Er besteht aus Tanzsaal, mehrere Räume für unterschiedliche Nutzungen und einer Terrasse zum Meer.

«Gleich zu Beginn zieht uns der Festpavillon an, dessen Beine aus den Wellen ragen, wärend die Veranda über das Meer hinausgeschoben ist. Drinnen spielt Musik und fröhliche Paare tanzen den Boston; aussen tauchen aufgehängte Lampions alles in ein märchenhaftes Licht, in welchem sich Damen und Herren intim unterhalten, wie in Tausend und einer Nacht» schreibt Petru Vulcan

Seitenansicht mit Fenster über der Treppen ©dstoica

Seitenansicht mit Fenster über der Treppen ©dstoica

Zuerst werden die Räumlichkeiten extern vermietet, danach wird das Gebäude von der Stadtverwaltung Constanţa in Eigenregie verwaltet. Ziemlich bald wird festgestellt, dass der Gewinn die Instandhaltungskosten kaum übersteigt; die Stadt bietet die Räume wieder zur Vermietung an. Mai 1902 bewirbt der einzige Sohn des Ion Creanga – ein grosser rumänischer Schriftsteller – sich als Mieter: Kapitän Creanga ist Bäcker und Konditor und spricht die damals gängigen zwei Fremdsprachen. Er bekommt das Gebäude für 2’000 lei im Jahr, unter den Bedingungen, dass er «Konsumartikel bester Qualität» verkauft und für die Beleuchtung «Petroleum bester Qualität, um Geruchentstehung zu vermeiden» benützt.

Das Kasino wird zur Hauptattraktion der Stadt, an sämtlichen Abenden im Juli und August finden Konzerte zwischen 5-7 Uhr und 8-12 Uhr statt, die bedeutendsten Orchester der Zeit treten auf; man kann sich ein Saisonabonement kaufen.

«An ruhigen Abenden füllen sich die zwei Terrassen des alten Kasinos mit vornehmer Gesellschaft, die draussen diniert, vor dem in Dunkelheit gehülltem Meer, und lauscht den den täuschenden Klängen des Orchesters». Der alte Holzbau steht auf kräftigen Stützen, am Rand des Boulevards. In dem improvisierten Salon freuten sich und feierten während vieler Saisons Leute aus ganz Rumänien und aus aller Welt Bälle und rauschende Feste. Heute scheinen die Erwartungen gestiegen zu sein und die Leute schauen voller Mitleid auf die alte Baracke, die einst so viele Stelldicheins und Extase barg.» “Malerisches Constanta” – Ion Adam

Somit war die Architektur des Gebäudes bereits zu Beginn des 20. Jh. aus der Mode gekommen; die Stadtverwaltung wünscht ein modernes Kasino zu errichten, im Stiel der Bauten der französischen Riviera.

Architekt Daniel Renard wird mit dem Projekt beauftragt, er ist 32 Jahre alt und hat die Ecole des Beaux Arts absolviert. Sein Vorschlag, ein Jugenstilgebäude zu bauen, ist zunächst sehr umstritten: von den Liberalen, die gerade an der Macht sind, sehr ermutigt, wird das Projekt von der gesamten Opposition scharf kritisiert. Die Arbeiten beginnen, jedoch endet das Mandat der Liberalen, und die neu gewählten Konservativen stoppen den Bau. Sie ersetzen den Architekten Renard mit ihrem Favorit, dem berühmten Petre Antonescu, welcher ein Theater – ähnliches Gebäude mit zwei Türmen vorschlägt. Die Arbeiten an der neuen Gründung beginnen. Inzwischen geht auch das Mandat der Konservativen zu Ende – und die Liberalen werden 1907 wieder gewählt. Auf der dritten Gründung wird schliesslich zwischen 1907 und 1910 das heutige Kasino gebaut, Kostenpunkt 1.3 Mio lei.

Das Fenster über der Treppen, Innenansicht

Das Fenster über der Treppen, Innenansicht

Viele mögen den Bau nicht. Zum Beispiel einem französischen Diplomaten,

ᅠGeorge Oudard,welcher 1935 Constanta besucht, erscheint das Kasino- Gebäude als furchtbar.

Er schreibt in seinen Reisebericht: «eine Sache ist an diesem freundlichen Ort enttäuschend: das weisse Kasino, anspruchsvoll und kompliziert , im schrecklichsten Stile des 1900, welches das Meeresufer beladen aussehen lässt.»

Meist war die zeitgenössische Kritik nicht gnädiger und brauchte das Kasinogebäude oft in den Schlagzeilen unterschiedlicher politischer Auseinandersetzungen. In einer Nummer vom März 1910 beschreibt die Zeitung «Conservatorul Constantei» das Kasino als ein «mit lauter unterschiedlichem Flitter geschmücktes Ungetüm». Im Dezember 1911 kritisiert die Zeitung «Drapelul» (die Flagge) den Bürgermeister Titus Cananau, weil er als Chefingenieur die Pläne und Baugesuche genehmigt hat, obwohl er «in seiner Stellung als Leiter des Technischen Dienstes und Mitglied des Baurates den Bau des Ungeheuers hätte verhindern können und müssen.»

Fürst Ferdinand eröffnet am 15. August 1910 das Kasino, dessen Verwaltung Alphonse Hietz, Hotel- und Restaurantbesitzer aus Bukarest übernimmt.

Der Raum mit der Bühne. Fenster in Muschelform, typisch Jugendstil

Der Raum mit der Bühne. Fenster in Muschelform, typisch Jugendstil

Gegenüberliegende Wand im selben Raum

Gegenüberliegende Wand im selben Raum

Um die enorme Investition für den Bau zurück zu gewinnen, autorisiert die Stadtverwaltung im März 1911 die Glücksspiele. Zwei Billardtische und 17 runde Kartentische werden zur Benutzung gestellt. Alsbald kommen Spielsüchtige und Abenteurer aus der ganzen Welt zum feiern und spielen her, wo der Luxus und die Eleganz zu Hause sind. Im Kasino finden leidenschaftliche Dramen statt – und sagenhafte Reichtümer wechseln ihre Besitzer innert kürzester Zeit. Manche der Verlierer werfen sich in die Wellen oder erschiessen sich in einem Hotelzimmer in der Nähe.

Der Baron Edgar de Marcay lässt 1912 das Hotel Palace bauen – speziell für die Kunden des Kasinos, wie mit der Stadtverwaltung vereinbart (Mein Grossvater, arch. Agripa Popescu, gestaltete die Inneneinrichtung in den 1970er Jahren, als das Hotel saniert wurde).

Im ersten Stock. Links die Tür zum Spielraum, vorn kommt man zu einem Festsaal

Im ersten Stock. Links die Tür zum Spielraum, vorn kommt man zu einem Festsaal

Entgegen aller Kontroversen behält das Kasino seine ursprüngliche Funktion über die Jahre hinweg, mit einer einzigen Ausnahme: im Ersten Weltkrieg wird das Gebäude als Spital benutzt – und vom Meer aus beschossen.

In der Zwischenkriegszeit strahlt das Kasino wieder in seiner alten Pracht. Das Gebäude, welches eine Baufläche von 801m² misst, wurde 1956 denn auch unter Denkmalschutz gestellt.

2005 wird das Kasino geschlossen und zur Konzession angeboten.

Ein Jahr später, Januar 2006, zeigt nur die israelische Firma “Queen”, welche auch Casino Palace in Bukarest besitzt, Interesse. Die Firma plant eine Neueröffnung in der zweiten Hälfte des Jahres 2009, mit erweitertem Programm für VIPs.

Realitatea.net schreibt im Juni 2007:

Nach zwei Ausschreibungsetappen, zum Zeitpunkt der direkten Verhandlung, wurden die Vorgänge angehalten. Die Ausschreibung war international, erschien in der Presse und wurde auch in der Zeitung der EU angezeigt, jedoch verordnete die Regierung, dass auch ein Beamter des Kulturministeriums der Ausschreibungs – Kommission beiwohnen, erklärte der Bürgermeister Radu Mazare. Das Kulturministerium hat sich danach geweigert, eine Person für das Komitee zu nominieren, mit der Begründung, die nötigen Verfahrensnormen existierten noch nicht. Die Stadtverwaltung Constanţa startete ein Anzeigeverfahren, danach wurde rasch ein Beamter des Kulturministeriums nominiert. Die Verhandlung mit der Firma Queen, immer noch die einzig interessierte, wurde eine Woche später mit einem Vertrag beendet.

Luftansicht, vom Meer aus © Stadt ConstantaDas Kasino auf der Küste wird der israelischen Firma für 49 Jahre in Konzession übergeben, mit einer Verlängerungsmöglichkeit für weitere 24 Jahre. Die Lizenzgebühr beträgt 140’000 € pro Jahr und fliesst in den Gemeindehaushalt ein; dazu wird der Betreiber verpflichtet, 9 Mio. € in die Restaurierung des Gebäudes zu investieren.

Luftansicht, vom Meer aus © Stadt ConstantaDas Kasino auf der Küste wird der israelischen Firma für 49 Jahre in Konzession übergeben, mit einer Verlängerungsmöglichkeit für weitere 24 Jahre. Die Lizenzgebühr beträgt 140’000 € pro Jahr und fliesst in den Gemeindehaushalt ein; dazu wird der Betreiber verpflichtet, 9 Mio. € in die Restaurierung des Gebäudes zu investieren.

Das Zeitfenster fürs Renovationsprojekt erstreckt sich auf ein halbes Jahr hinaus, danach beginnen im Anschluss die Sanierungsarbeiten, wenn das Bauvorhaben bewilligt wird.

Je nach Ausgang des Gutachtens werden sowohl die Tragstruktur, als auch die Innenräume saniert.

Meine Fotos stammen aus 2007, als an einem Septembertag im unteren Teil des Gebäudes eine Hochzeitsfeier vorbereitet wurde. Durch die Säle im Erdgeschoss liefen eilig Kellner umher und deckten die festlichen Tische, im oberen Geschoss flogen Tauben durch den Saal mit der Bühne – deren Spuren man auf den Fotos erkennen kann.

Durch Anklicken der kleinen Fotos gelangst Du direkt zur Galerie der Kasino-Fotos.

Dear reader,

What you’ll find here:

– Fresh stories at ‘Diurnal‘, structured in: Family, Buildings, Personal

– the ABC of feelings: A like Angst and B of the Blues, C stands for Chaos, D for Déja-Vu…

– some travel stories from India (2012) and Haiti (2011),

– research about decaying monuments (în Romana/auf Deutsch)

***

Teasers on diurnal: The Missed Flight, Weeds, The House, English Lessons & The Tree