September 1981. My parents brought me to kindergarten, where I spent the entire first year not speaking any word at all. I was too busy wondering about everything and everybody in this new environment.

Every morning at a quarter to eight, one of our family took me down the street towards the market. On the left side, between two blocks of flats there was a hidden alley, which went behind them, on to a green gate and fence. Passing the gate, a garden with roses on the right and a sandbox on the left; between them, a path to a yellow house with three steps and a green door.

There I met Aunt Ann, who became my grandma no.3.

I went to kindergarten every day from 8 to 12 for six days a week for five years. Aunt Ann used to have all three age groups in the same big room and she was able to keep us all busy. She’d sing with us, playing her guitar, we’d exercise together and draw and do handicrafts, while we’d all be surrounded by her beautiful British accent like in a dream.

I started talking in the second year of kindergarten, suddenly and without any warning.

This private kindergarten existed in spite of the system. It closed in 1986, the year I went to school, because dear Aunt Ann had gotten too ill to go on with it. She kept giving English lessons and I kept going to these twice a week for the next 10 years.

I learnt so many things from her, also about what should but cannot be spoken about. It probably was the one of the last memories of someone teaching me stuff without trying to break me.

***

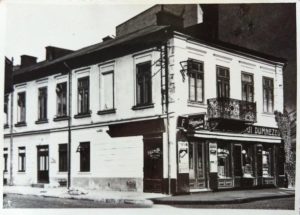

Aunt Ann was born as Annemarie Fischer in 1915. Her sister Lieselotte arrived in 1922. Their parents were of German origin; the father, an architect, had built the house in the back in 1916-18 and the house in front in the nineteen twenties. Annemarie had gone to Oxford to improve her language skills for at least a year. She had married Toni Böttcher, her colleague at Astra Romana, the oil refinery company that was part of the Royal Dutch Shell trust between 1911-1947. The couple had a daughter in 1941.

War came and Romania went in on the Axis’ side first. Toni couldn’t go to war, because his hands that once played the piano so well were now impaired after a bike accident and subsequent gangrene due to a too tight cast.

Romania switched sides on August 23rd, 1944.

That same month former Soviet Ambassador to the UK, Ivan Michailovitch Maisky proposed the deportation and re-education of German active nazis and war criminals in work camps as a ‘post-war reparation’ to the Allied representatives in London. On September 12th, 1944, Romania signed a ceasefire, which did not stipulate reparations in workforce.

Meanwhile, Soviet troops had reached the Balkans.

October-November 1944, all German ethnics of Romania were called to submit their names on lists at the police station. They were told they could go visit their relatives in Germany if they did so. The queues were long and Annemarie and Toni got in that day, but the counter closed in front of Lieselotte, who was supposed to come back the next day. She didn’t go anymore, annoyed by the long lines.

What they didn’t know was that Stalin had allegedly asked, among other reparations, for 100’000 workforce from Romania, among other reparations. Our new ally had passed their State Defense Committee Order 7161 on December 16, 1944*.

Christmas and New Year’s Eve passed and on January 12th, 1945, the Red Army started seizing all people on the lists, one by one. In less than a month, all German ethnics of working age were snatched from their homes: men of 16-45 and women of 18-30, if they were not pregnant or had any babies under the age of one. Some tried to escape and fled to the mountains, others hurriedly married Romanian ethnics. Their families were pressed to give up on their relatives, regardless of the family situation.

Toni and Annemarie were seized in their garden – she just had time to pass her 4-year-old daughter to her sister’s arms, on that same lovely path I later walked on to kindergarten every day.

They were separated, put on livestock wagons and sent to work in the coal mines around Donetsk, were they worked for more than one year, not knowing if either was still alive or if there’d ever be a ‘back home’ one day.

The Romanian King and government protested in January: according to the armistice, Romanian civil citizens of any race and religion were supposed to be protected by the Allies. At the Conference in Yalta in February 4th -11th, 1945, the U.S. and UK raised some objections to the Soviet use of German ethnic civilian labor, arguing that the „reparations in kind“ were done in the name but without the agreement of the Allies. By then, the process was already closed; Maisky was deputy foreign minister. Churchill allegedly concluded, „Why are we making a fuss about the Russian deportations in Romania of Saxons and others?“

Some time in 1946 Annemarie was released, on the grounds that ‘there was no one else to take care of the family’. She returned home and, some time later, Toni did as well. They changed their name from Böttcher to Dogaru, which meant the same, but in Romanian: barrel maker. They had another daughter in 1947. But they never got along anymore after Donets Basin, so they separated, eventually.

Her health was shaken and she couldn’t work anymore, so she started with the kindergarten. It was the 1950es, 30 years before I walked into that garden for the first time.

Listening to Radio Beromünster in 1946

Listening to Radio Beromünster in 1946

Today I helped grandma out with the Christmas tree. I climbed up the ladder and got the box with the decorations down from the top shelf. The box!… one more piece that survived from the pharmacy!

Today I helped grandma out with the Christmas tree. I climbed up the ladder and got the box with the decorations down from the top shelf. The box!… one more piece that survived from the pharmacy!