Preluat de pe site-ul OAR – https://oar.archi/timbrul-de-arhitectura/de-vorba-in-biblioteca/

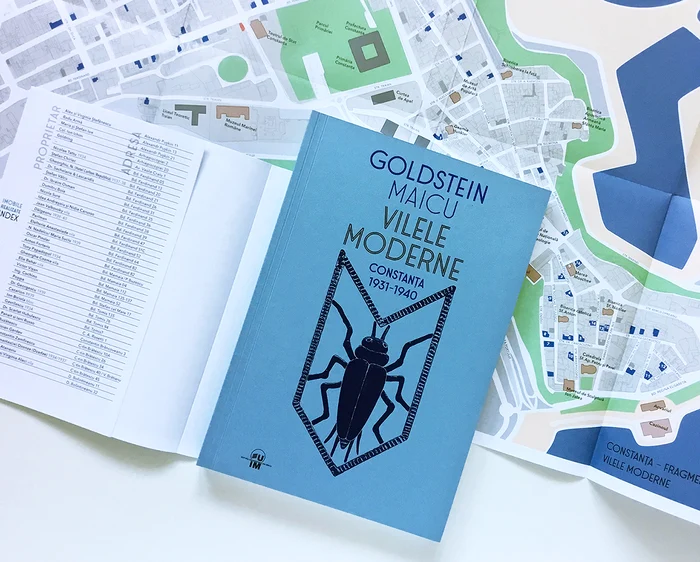

“Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931–1940” – cartea care ajută la renovarea caselor ale căror povești le spune

📁 Link catre carte pe site-ul librăriei

Autor: Ciprian Plăiaşu, 17 august 2023.

Preluat de pe Historia.ro.

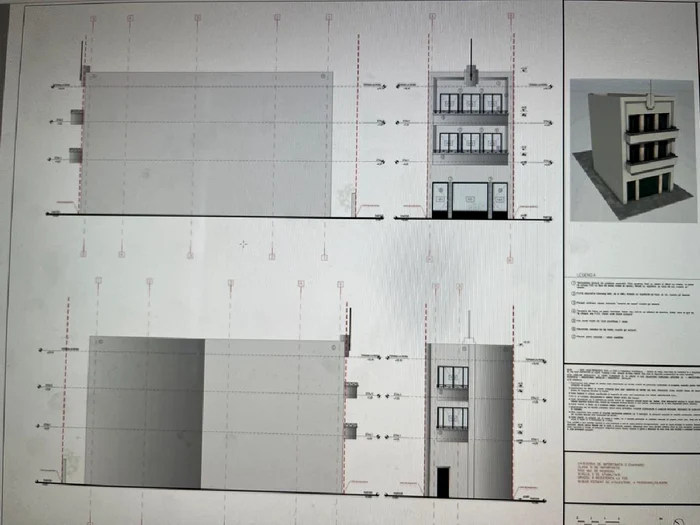

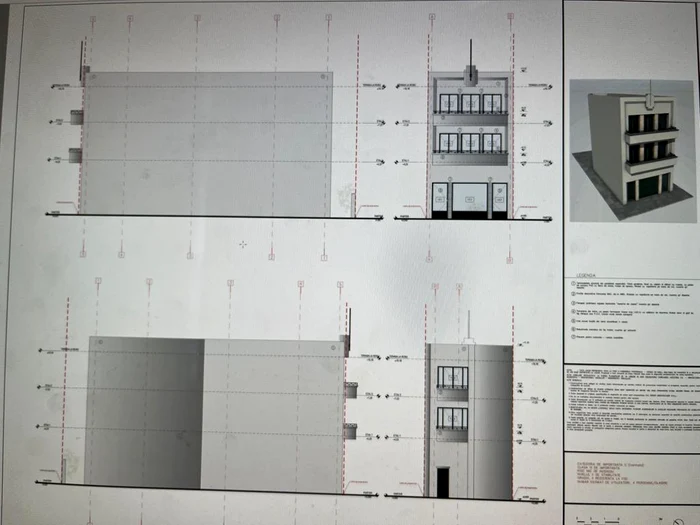

Imagine din cartea Maicu Goldstein, pagina 7 – Croitoria Gavrilescu, Constanța.

“Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931–1940” este un proiect editorial al OAR, finanțat din timbrul de arhitectură și coordonat de arh. Dorothee Hasnaș. A fost lansată pe 23 martie 2023, la sediul Filialei Teritoriale București a O.A.R. din str. Sfântul Constantin nr. 32, sector 1.

Cartea aduce în atenția specialiștilor și a publicului larg o decadă din istoria arhitecturii Constanței, marcată de activitatea prolifică a unui tânăr arhitect evreu – Haim (Harry) Goldstein, devenit după război o personalitate importantă a mediului profesional și academic și trage, în același timp, un semnal de alarmă asupra stării avansate de degradare și mutilare a imobilelor care au rezistat până astăzi.

După intrarea în librării, tirajul de 700 de exemplare s-a epuizat în timp record și publicul cere reeditarea de urgență a volumului, ajuns la preț de speculă pe siteuri online. Reeditarea volumului “Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931–1940” este un pas firesc.

Cu apariția cărții, mai mulți proprietari de apartamente/imobile din Constanța și-au putut regăsi fațadele caselor în schițe sau fotografii de epocă.

În iunie 2023, autorii cărții au primit un mesaj de la proprietarul imobilului din B-dul Tomis nr. 45 (Constanța) – Casa Gavrilescu, care a aflat din carte despre autorul imobilului:

“Având în vedere că dorim ca această renovare să fie cât mai fidelă cu clădirea inițială, sperăm să ne ajutați să intrăm în posesia proiectului sau a altor documente ce ne-ar putea fi de folos. În iulie, am primit aviz de la comisia de monumente pentru lucrările de renovare a imobilului, ajuns între timp într-o stare de ruinare avansată, inclusiv lipsa etajului superior.”

Despre “Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931–1940”

Cum arăta peisajul socio-economic al orașului atunci și cine erau comanditarii acestor imobile?Ce s-a mai păstrat din modernismul constănțean? Ce a supraviețuit brutalelor intervenții contemporane? Cum se integrează arhitectura acestor imobile în orașul de astăzi?Ce trebuie să aibă în vedere măsurile de consolidare?

Stadiul lucrărilor in noiembrie 2024

Povestea Constanței de atunci, detalii din peste 60 de imobile și din arhiva cu sute de schițe care a dus la construcția vilelor, peste 300 de fotografii de epocă și de azi. O propunere de tur prin peninsulă. Un ghid de bune practici în mentenanța și renovarea imobilelor moderniste. Indexul vilelor. Toate acestea se găsesc în paginile cărții.

Cartea răspunde acestor întrebări născute firesc, odată cu descoperirea colecției de arhivă într-o pubelă de pe strada Batiștei în 2014 și se prezintă ca un ghid pentru un day trip/city break la Constanța: pe drum în tren poți citi prima parte, contextul, apoi face singur turul – supracoperta include harta peninsulei și arată principalele imobile Goldstein. Iar la întors poți citi mai pe larg despre case și detaliile lor.

Mai multe găsiți online pe maicugoldstein.ro.

Constanța arhitectului Haim Goldstein (Horia Maicu): Salvarea, uitarea şi din nou salvarea lui Maicu

Arhitectul Horia Maicu, născut Haim (Harry) Goldstein, a reintrat în actualitate după salvarea spectaculoasă a arhivei sale dintr-un tomberon de pe strada Batiștei de către pictorul Daniel Balint, care trecea pe acolo întâmplător în ianuarie 2012. Mulţi au luat atunci pentru prima dată contact cu cel care a fost arhitectul-șef al Capitalei între 1958 și 1968 și care și-a pus semnătura pe o serie de clădiri-simbol ale Bucureștiului – Combinatul Poligrafic „Casa Scânteii” (astăzi Casa Presei Libere), Teatrul Naţional, Sala Palatului, mausoleul din Parcul Carol etc.

În bena de gunoi de pe strada Batiștei, de lângă faimosul „bloc roșu”, proiectat chiar de Horia Maicu și unde arhitectul avea un apartament, s-a găsit arhiva personală a acestuia ‒ arhivă care aduna atât faimoasele sale edificii bucureștene, cât și o altă lume, cea a debutului său în arhitectură, în orașul său natal, Constanța. Horia Maicu a locuit în „blocul roșu” pe strada Batiştei, în Bucureşti, până la moartea sa, în 1975, iar în 2012, noii proprietari nu au înțeles valoarea arhivei aceluia care fusese arhitectul-şef al Capitalei în perioada lui Gheorghiu-Dej și au aruncat-o alături de moloz, haine şi bucăţi de mobilă.

Salvarea, uitarea şi din nou salvarea

Vreme de câţiva ani, recuperarea de la gunoi a arhivei lui Horia Maicu nu a prezentat mare interes. Abia în 2015 a fost organizată o expoziție în foaierul Teatrului Național din București și, în acest moment, publicul larg l-a descoperit/redescoperit pe Horia Maicu și a aflat istoria arhivei sale. A curs ceva cerneală în perioadă, apoi s-a așternut din nou liniştea.

În 2022, un grup de specialiști sub coordonarea arh. Dorothee Hasnaș a reluat cercetarea cu privire la fostul arhitect-șef al Capitalei. Perioada abordată în cercetare, finalizată cu lucrarea Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931-1940, este cea a debutului lui Horia Maicu, pe atunci Haim Goldstein, în lumea arhitecturii. Descoperirile sunt fabuloase: peste 100 de imobile ridicate în 10 ani, o amprentă unică păstrată în feronerie și detaliile imobilelor și niciun strop de realism-socialist în lucrările sale. De asemenea, cercetătorii au descoperit că arhiva salvată în 2012 era volantă și au făcut toate demersurile ca aceasta să ajungă în administrarea unei instituții care să fie capabilă să o ofere publicului pentru consultare.

Astăzi, arhiva Goldstein-Maicu este în administrarea Ordinului Arhitecţilor din România, iar numele salvatorului, pictorul Daniel Balint, se află la loc de cinste.

Constanţa se modernizează

La începutul celei de-a doua jumătăți a secolului al XIX-lea, Constanța se află încă la marginea Imperiului Otoman. Orașul din epocă e un port mic, vechi și cosmopolit, cu arhitectură preponderent rurală.

Într-un fel, orice oraș-port este definit de mare: el nu funcționează la fel în toate direcțiile, ca un oraș de șes, ci se orientează cu totul către mare, ca un amfiteatru. Este, prin definiție, un oraș deschis, care intră în contact cu diferite culturi și influențe, prin traficul maritim.

Neschimbată de veacuri, relativ liniștită, zona trece la sfârșitul secolului al XIX-lea printr-un un război cumplit, în care câștigă teritorii și se afirmă cu un rol nou, intrând într-o perioadă cu adevărat specială.

Schimbarea la faţă

Pentru orice modernist, orașul Constanța datorează enorm Regelui Carol I. După Războiul de Independență și Pacea de la Berlin, din 1880, România dobândește, în urma unui schimb de teritorii, Dobrogea, un teritoriu eterogen din punct de vedere al populației și religiilor. Un ordin al primăriei referitor la aplicarea legii stării civile, din 28 decembrie 1878, menționează bisericile greacă, bulgară, catolică și templul așkenazilor (1). De asemenea, recensământul din 1880 arată că orașul Constanța avea doar 5.204 locuitori (2), paisprezece ani mai târziu, numărul se dublase (3), iar în 1904 ajunsese deja la 13.385 de locuitori (4), pentru ca, după Primul Război Mondial, în 1928, să numere 40.933 de locuitori (5).

Totuși, pentru proaspătul rege, Dobrogea reprezenta acel teritoriu de care avea mare nevoie în dorința sa de a dezvolta și a moderniza tânărul stat român. Cele trei județe din sudul Basarabiei (Cahul, Ismail și Bolgrad) reprezentau o ieșire la Marea Neagră, dar una dificil de administrat. Crearea unui port de anvergura Hamburgului, din Germania natală, așa cum își dorea Carol I, era imposibilă în acest spațiu, însă Constanța îndeplinea toate criteriile. Singurul mare obstacol era traversarea Dunării.

Construirea podului de la Cernavodă de către inginerul Angel Saligny, între 1890 și 1895, a adus un și mai mare avânt în dezvoltarea celui mai mare oraș-port al țării. De altfel, la data de 16 octombrie 1896, Regele Carol I, într-o ceremonie fastuoasă, punea piatra de temelie a construirii Portului Constanța (6).

Deși orașul reprezenta un punct comercial și turistic, pe linia vestitului tren Orient Express, administrația regală românească a oferit Constanţei, la finele secolului al XIX-lea și începutul secolului XX, un impuls extraordinar în dezvoltarea sa. Înființarea Serviciului Maritim Român (1887), dar și dezvoltarea unor clădiri publice-simbol ‒ palatul comunal (care a avut chiar două sedii: prima clădire, inaugurată în 1896, este azi Muzeul de Artă Populară, cea de-a doua clădire, din Piața Ovidiu, a fost inaugurată în 1921), palatul administrativ, palatul de justiție, palatul episcopal, teatrul, muzeul, biblioteca, spitalul și, bineînțeles, Cazinoul (1905-1910) ‒ au schimbat fundamental fața orașului.

Hoteluri şi locuinţe private luxoase

Construcțiile administrative au fost secondate de investiții private. Astfel, remarcăm apariția unor locuințe private luxoase și impunătoare precum: palatul Sturdza (autorizație obținută în 18897), locuințele lui Amédée Alléon, Vila Sutzu (1898-1899), Casa Hrisicos (1903), Casa Pariano (sfârşit de secol XIX), Casa Petre Grigorescu (sfârşit de secol XIX), Casa cu lei (1895), Casa Manissalian (1905) etc. Citind mărturiile de epocă și corelându-le cu informațiile statistice, observăm o întreagă elită care se formează din oameni pregătiți, de care noul oraș are mare nevoie.

De asemenea, de la cele câteva cârciumi și hanuri, după 1880, apar numeroase hoteluri: Hotel d’Angleterre, Hotel Gabetta, Hotel Ovidiu, Hotel de France, Hotel Metropol, Hotel Carol I, Hotel Palace, Hotel Europe Elite, Hotel Mercur, gata să asigure servicii de la cele mai simple la cele mai rafinate gusturi.

Se schimbă şi modul de a călători

Constanța interbelică continuă să fie un punct de atracție pentru călători și un nod comercial deosebit, însă apar tot felul de elemente de modernitate. Încet-încet, birjarii fac loc automobilelor, iar călătoriile cu avionul nu mai sunt ceva exotic. În 1934, şapte avioane au efectuat curse pe ruta București – Constanța – Balcic – București. Cursele aeriene deveniseră și ele regulate, e drept, pentru elita care își petrecea vacanțele la Balcic și pe întreaga Coastă de Argint.

Încă din 1920, pe strada D.A. Sturdza (azi Revoluției), într-o clădire foarte frumoasă, Casa Embiricos, își deschidea birourile compania transatlantică American New East & Black Sea Line – linie regulată, rapidă și directă Constanța – New York. „Pe parcursul voiajului se pun la dispoziția celor interesați și în funcție de tarif mâncare, muzică, cinematograf și baie”8.

În anii ’30, Serviciul Maritim Român avea aici 14 nave de pasageri care efectuau curse în întreaga lume. Poate o parte dintre acestea au fost surse de inspirație pentru tânărul Haim Goldstein în dezvoltarea stilului său modern, asemănător cu imaginea unui pachebot. Rutele cele mai importante erau: Constanța – Varna – Istanbul – Salonic; Constanța – Istanbul – Pireu – Alexandria; Constanța – Istanbul – Pireu – Beyrouth – Haifa etc.

Blocul Kalambotos din Constanţa, imobil realizat în 1934 în stil modernist

Cazinoul

Dincolo de băile de soare, care îndemnau pe toți să ajungă în sezonul estival pe plajele amenajate la Constanța, principala atracţie a urbei a fost, începând din anul 1910, evident, Cazinoul Comunal, monumentalul edificiu construit de către arhitectul Daniel Renard, în stilul Art Nouveau.

Locul unde se făceau sau se pierdeau averi, la ruletă, la bacara sau la alte jocuri de noroc celebre la acea vreme în lumea întreagă. Bineînţeles, Cazinoul Comunal însemna mai mult decât atât: era şi centrul cultural al oraşului, loc de spectacole, expoziţii şi numeroase alte evenimente, dar şi, graţie falezei sale, locul ideal pentru promenadă.

Aceasta este, în câteva tuşe, Constanţa în care a trăit şi activat Haim Goldstein…

Tânărul arhitect Haim Goldstein şi locul său în Constanța interbelică

În 1905, în Constanţa, în casa din strada Libertății nr. 21, se naște Haim ‒ fiul Clarei Herscovici și al cârciumarului Marcu Goldstein. Douăzeci de ani mai târziu, tânărul absolvă liceul și pleacă în Italia, la Roma, cu o bursă de studii. În 1930, revine în orașul natal cu diplome în inginerie și arhitectură şi demarează o seamă de șantiere în antrepriză cu alți arhitecți.

Un element interesant este şi evoluția comunității etnice a arhitectului. Pentru că Haim (Harry) Goldstein este evreu, putem urmări, în traseul său, şi evoluția comunității așkenazilor. Astfel, la momentul intrării Dobrogei în Regatul României, aceasta număra vreo 234 de suflete, în preajma nașterii lui Haim, 1.059, iar în ajunul întoarcerii sale în Constanța de la Roma, 1.050.

Peste 100 de imobile în zece ani

Într-un interval de numai zece ani, între 1931 și 1940, arhitectul participă la construirea a peste 100 de imobile. Astăzi le numim „vile”, deși multe erau, de fapt, „apartment houses”, Blockhaus-uri, imobile P+3 sau 4, cu câte două apartamente pe etaj, un gen de construcție tipică perioadei. Arealul intervențiilor lui Goldstein se extinde peste marginile Constanței, incluzând lucrări în Mamaia, Techirghiol, Eforie, Palazu Mare, poate chiar Silistra.

Multe din aceste imobile se găsesc încă pe străzile Constanței, nevăzute și neștiute, modificate în chip nefericit sau pur și simplu ascunse privirii. Sunt necunoscute, pentru că nu s-a vorbit de ele până acum. Multe au fost descoperite, de altfel, în timpul cercetării arhivei Goldstein, în colecția impresionantă de schițe găsite în pubela din centrul Capitalei.

Schițele făceau odată parte din viața arhitectului Horia Maicu, care nu doar că a participat la proiectarea Combinatului „Casa Scânteii” (1953-1959), ajungând director la Institutul de Proiectare a Construcțiilor și apoi arhitect-șef al Capitalei între 1958 și 1969, dar a şi predat la Institutul de Arhitectură „Ion Mincu” începând cu 1950, locuind într-un apartament dintr-un bloc proiectat chiar de el, pe strada Batiștei nr. 11, împreună cu soția, Sultana, până în anul morții, 1975.

„Ce frumos e desenată fațada”. Tăcere…

În anii aceştia, Haim Goldstein e Horia Maicu, cel care a întors complet spatele perioadei sale constănțene. Cât de mult se detașase de trecutul său rezultă dintr-o anecdotă povestită de arhitectul Romeo Belea, care a lucrat cu el timp de şaptesprezece ani. Mergând odată la Constanța, Belea remarcă o casă de pe bulevardul Ferdinand și spune: „Ce frumos e desenată fațada”. Maicu se oprește și nu spune nimic, doar se uită lung. Era unul din imobilele Goldstein.

Dar, în acele vremuri, Maicu era doar Maicu, în Constanța se construiau blocuri socialiste și Cazinoul ajunsese un local de alimentație publică.

După anii ’50, România trăiește un nou boom imobiliar, declanșat de industrializarea forțată și de determinarea noului regim de a crea noduri industriale, cel dintâi fiind în jurul Capitalei.

După oprirea șantierelor comuniste, la finele lui 1989, România trece printr-o perioadă de somn al Cenușăresei și ajunge astăzi din nou la o nemaipomenită hărnicie imobiliară: de această dată însă, imobilele care nu sunt demolate sunt desfigurate cu intervenții ieftine, care rașchetează detaliile atent construite în anii ’30 și le înlocuiesc cu ready-mades barbare. Hublourile, antenele, artropodele de pe uși nu se mai pot apăra de intervențiile nefaste ale gospodarilor porniți să le înnoiască ‒ citește: înlocuiască ‒ cu orice preț. Lumea de azi nu le mai știe valoarea, prețuind noul, fără a ști să discearnă calitatea.

Lecţiile arhivei Maicu

Arhiva schițelor lui Maicu, găsită în tomberon, păstrată timp de un deceniu de pasionați, a ajuns, în fine, în biblioteca Filialei București a Ordinului Arhitecților din România în toamna lui 2022: a venit momentul oportun ca ea să ne deschidă ochii asupra migalei cu care arhitectul trata pe atunci rezolvarea partiruilor și a fațadei, propunând variante multiple, dar și ca să ne vorbească de o vreme când arhitectul era puternic, beneficiarul îi respecta rolul și constructorul îi urma întocmai planurile. Altceva ar fi fost pe atunci de neconceput.

Acest stop-cadru asupra perioadei constănțene a lui Haim Goldstein (Horia Maicu), prea puțin cunoscută astăzi, ne oferă o sumedenie de imagini: cum era orașul-port atunci, cum s-a dezvoltat, cine își putea permite o vilă semnată Goldstein, cum se explică Modernitatea și Modernismul, prea des confundate cu Art Deco și Bauhaus.

Calambotos, Askitopoulos, Xenakis și Hurmuziadi (greci), Russo, Solaris, Dalla și Cochino (italieni), Goldfeld și Heilpern (evrei), Nedelcu și Huhulescu (români), Calpagioglu și Cuimudoglu (turci) s-au numărat printre comanditarii imobilelor semnate de Goldstein. Mulți dintre ei antreprenori, legați deopotrivă de mare și de uscat și, mai ales, de orașul-port. Sunt oameni înstăriți, care își doresc noutatea, dar respectă standardele și valorile arhitecturale. De aceea, multe dintre imobilele păstrate atrag privirile turiștilor, cu uimire față de splendida construcție, dar și cu indignare la nepăsarea cu care sunt tratate azi.

Cum recunoaștem o casă din repertoriul Goldstein? Invitaţie la descoperire

Majoritatea imobilelor ridicate în Constanța interbelică de către Haim Goldstein se înscriu în stilurile „pachebot” modernist sau imobil cu iz mediteraneean. Există și unele excepții, iar volumul recent publicat, Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931-1940, dedică un capitol generos acestui subiect. Cartea include şi un capitol intitulat Vocabularul Goldstein, în care sunt prezentate forme și detalii arhitecturale, de la intrarea telescopică cu uși împodobite de insecte prietenoase și harnice (greierele, păianjenul, furnica și albina) până la ferestrele cu săgeata și soarele.

Pentru că imobilele au aproape o sută de ani, cititorul îşi va pune poate întrebarea: cum le putem renova, fără să pierdem din valoarea imobilului interbelic? Aceste aspecte sunt și ele surprinse într-un Ghid de bune practici, către finalul cărții.

Dar volumul Goldstein Maicu. Vilele moderne. Constanța. 1931-1940 propune şi un traseu (pe care îl redăm alăturat) în care veți putea descoperi pe teren imobilele Goldstein care au supravieţuit vremii, cu proporțiile lor zvelte și detaliile lor jucăușe, feroneria delicată a gardurilor, gângăniile pe ușile vilelor moderniste odată atât de însorite, la care intrarea și casa scării joacă rolul principal. Să privim prin ochii întredeschiși ce a rămas din ele astăzi, cu speranța că respectul pentru detalii va renaște înainte ca ele să dispară pentru totdeauna.

Mai multe găsiți online pe maicugoldstein.ro.

Articolul „O descoperire estivală: Constanța arhitectului Haim Goldstein (Horia Maicu)”, a fost publicat în numărul 260 al revistei „Historia”, disponibil la toate punctele de distribuție a presei, în perioada 15 septembrie – 14 octombrie, și în format digital pe platforma paydemic. (revista:260)

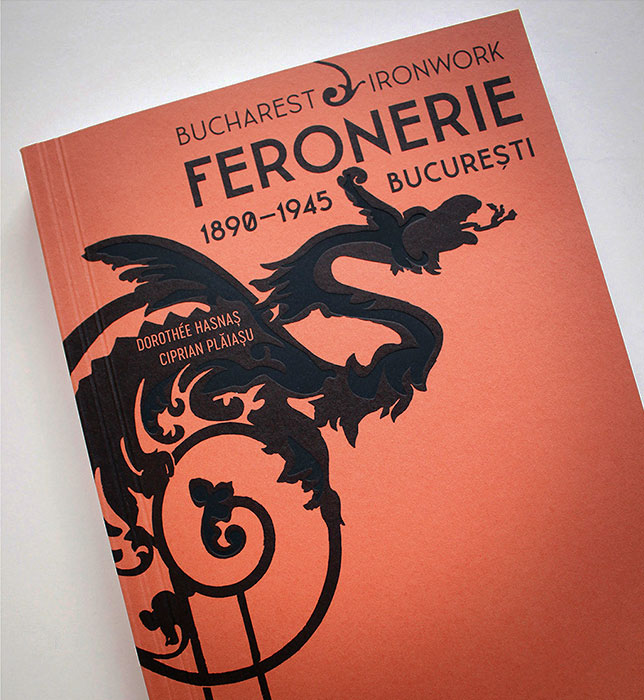

Feronerie. Ironwork. 1890 – 1945 Bucuresti

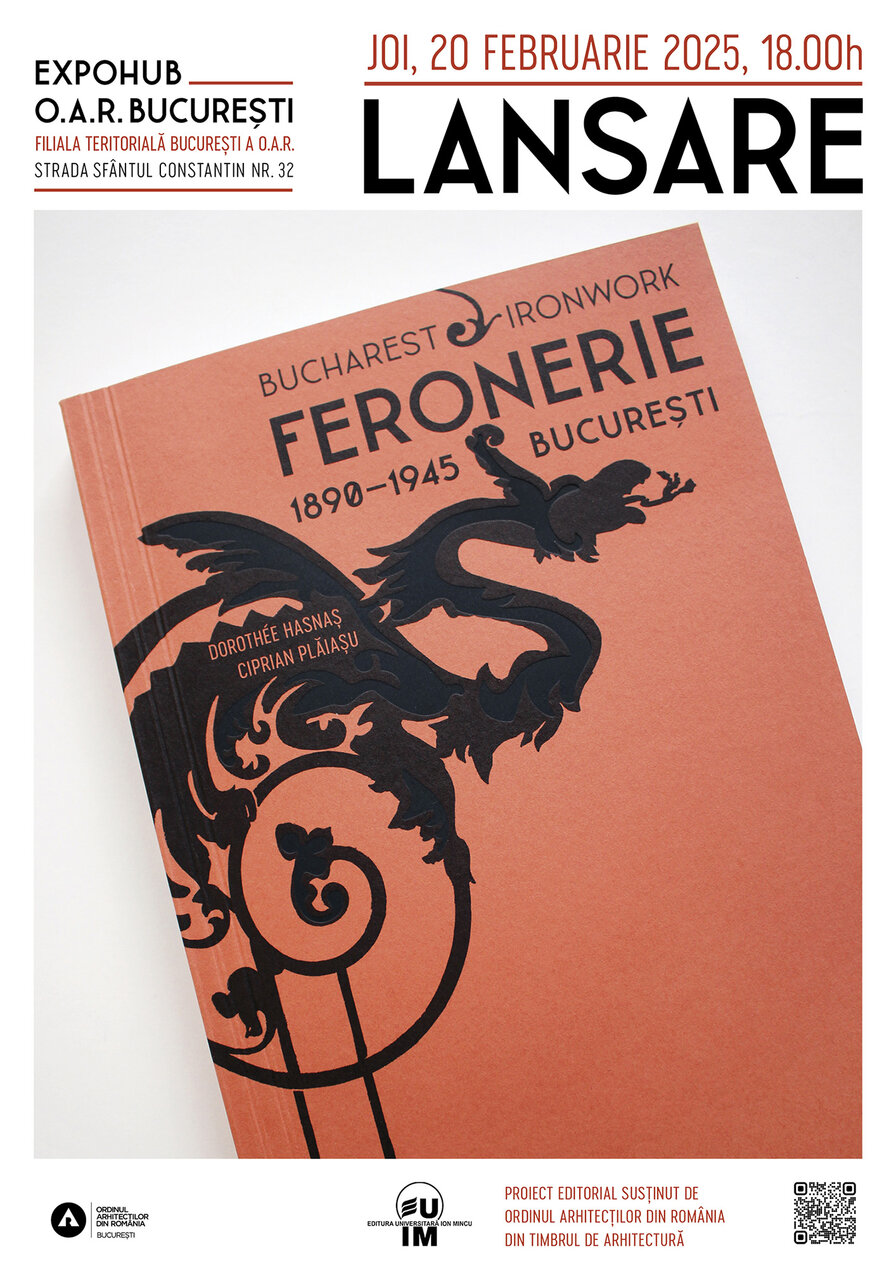

Lansarea cărții „Feronerie. București 1890-1945. Ironwork. Bucharest”

Editura Universitară „Ion Mincu” și Filiala București a OAR anunță lansarea volumului „Feronerie. București 1890-1945. Ironwork. Bucharest”, semnat de arhitecta Dorothée Hasnaș și istoricul Ciprian Plăiașu. Astfel, sunteți invitați la eveniment care are loc joi, 20 februarie, ora 18:00, la sediul Filialei București a OAR, din Str. Sfântul Constantin nr. 32. La eveniment vor participa specialiști în arhitectură, istorie, conservare și patrimoniu, dar și publicul pasionat de identitatea urbană a Capitalei.

De ce o carte despre feroneria bucureșteană?

Această lucrare documentează și analizează feroneria decorativă ca parte esențială a arhitecturii Bucureștiului între 1890 și 1945, o perioadă în care detaliile metalice erau integrate în stiluri diverse – de la eclectismul Belle Époque și neoromânesc, până la Art Deco și modernism. Același meșteșug era aplicat în registre stilistice diferite, reflectând rafinamentul tehnic și creativitatea atelierelor care le produceau.

Volumul subliniază importanța păstrării, întreținerii și restaurării feroneriei vechi, arătând cum aceste detalii sunt nu doar elemente de decor, ci parte din istoria și straturile orașului. Deși extrem de rezistentă în timp, feroneria este fragilă în fața neglijenței și a renovărilor grăbite, fiind prea ușor eliminată de pe fațade și din interioare.

O invitație la descoperire

Cartea propune și un tur pe strada Polonă, un loc unde arhitectura bucureșteană și-a găsit echilibrul între stiluri profund diferite, coexistând în aceeași perioadă istorică. Această diversitate este oglindită și în abordarea feroneriei – fie că vorbim despre balcoane neoromânești cu motive vegetale, garduri Art Deco cu linii dinamice sau scări moderniste cu balustrade minimaliste.

Volumul, realizat cu sprijinul Timbrului de Arhitectură, include peste 120 de imagini și exemple relevante de imobile din cartierele istorice ale Bucureștiului. Totodată, oferă recomandări pentru conservare și un ghid de bune practici, util atât proprietarilor, cât și specialiștilor din domeniu.

First aid kit

If you had a first aid kit with memories of the best moments of your relationship, what would you keep in there?

The day you got together. The first kisses.

Walking hand in hand on a chilly autumn day in a strange town.

A bunch of lillies you got on a random day. A hot summer afternoon.

A stolen hour, early on a Sunday morning.

A strong hug, just when you where about to fall apart.

A great advice for a work related issue.

The look in his eyes. Desire. Trust. “You`re going to make it.”

The small gestures. Cooking together.

There`d also be memories of hard times, when you stuck together.

That day, when everything felt like tumbling down and he just needed to be held in your arms.

A comforting talk, that took all your fears away.

The night where the kid was sick and one would wait for hours at the hospital.

The joyful anticipation of seeing one another the next day.

When you`re going through hard times, go on and open that box.

Look through the memories. Turn them over in your head – or in your palm.

Cultivate the good over the bad ones.

No use in endless rumination over the what ifs and whys.

Things will go their way, no matter what you do.

Make your own life nice, as no one else can do that for you.

And if you still end up on your own, don`t make it any harder on yourself.

These memories will stay with you as long as you need them.

It`s your box, after all.

Soap. Whiteshirt#16

Soap was one of the things that back in the 80es one would have a hard time obtaining. As everything else deemed as “luxury”: toothpaste, stockings, toilet paper…

There were some old and brittle pieces of soap hidden in grandma`s laundry drawer, but that was “the good soap”, so one was never to use it. It had long ago lost its smell, although grandma would swear she could still detect that fougère or lilly of the valley.

Sometimes in summer my parents would get hold of a piece housemade soap from somebody`s aunt. It was a misterious yellow-greyish chunk that we used for washing everything: our bodies, hair and the laundry. It smelled a bit acrid – “but it`s good for you” – it also left a weird sensation on the skin – I could never imagine how it was obtained just by boiling ashes and grease in a cauldron, but it seemed one could feel the process.

Why couldn`t they throw in some nice smelling flower to the mix? Lindentree or honeysuckle or whatever was growing by the roadside. Flowers were not restricted in any way…

One day a small miracle happened. I went through a drawer and tried to smell a mysterious greenish piece of soap that I had discovered there. It slipped and dropped to the ground, were it broke in two pieces.

Maybe now that it was damaged as an “untouchable memory”, maybe we could use it for washing?

It had a writing on it, so I took it to the sink and made it wet, in order to better decipher the letters on it. Something with Alep.

Once wet, it started smelling: clean-herbal-sweetish-different. It became smooth and shiny. It didn`t reek like the “housemade soap”. It felt nice on the skin.

I used it rarely and always with moderation and respect, for the next ten years: “mit Verstand zu geniessen” was a saying in our family for using valuable things – like chocolate or grandma`s quince jelly, rare finds – so as not to consume it all too fast: to enjoy with reason.

Years later I would actually get the chance to visit a soap manufacture near Aleppo, the place were soap was invented. I got to see how soap emerged in trays and was cut with threads, and walked between lattice walls made of olive-greenish soap chunks that were left out to dry, like brick walls (see it in a filmclip here). Olive and wood ashes (lye). Maybe some laurel oil.

The chunks had the colour of my little nugget from back then – I think I still had a miniature fragment in a drawer back then, in 2004. For the good day that was never to come.

All things have a finite lifetime. So I tossed it one day, as it had completely lost its smell.

Today I found this AlepiDerm soap in a store here in Bucharest. It`s perfect. And it suddenly brought all that back to me: the drawer and the broken soap, the smell of cleanliness and the walk through the Aleppo manufacture. They say, smell goes directly to your cerebellum, the “Kleinhirn“, the oldest part of our brain, not implying the cortex.

It did – and made me happy.

*the store is La Maison du Savon de Marseille, on Dr. Dumitru Râureanu 4, close to Piata Unirii.

This text is part of the WhiteShirtProject: Like a snake sheds its skin, I shed a series of white shirts while writing down memories – to be found in this link.

Bucharest, 2057

An article written for inclusiv.ro in 2020

A text about Bucharest in 2057, when my son will be my current age.

All photographs were taken by Stefan Tuchila as part of the Ultimul Etaj project.

Dear son,

You have won the elections… Congratulations! May it be a momentous occasion.

Somehow, we expected this outcome. Since you were little, I wondered what it would be like for you to one day rise to the leadership of this city that I have cherished so much, that I left behind and rediscovered much later: chaotic, dynamic, and challenging.

In essence, the signs were already present. One summer morning, when you were still in diapers, you went out on the 7th floor terrace of our apartment and proclaimed, “Today, I am the mayor! Come to my office,” and you invited us to the back of the terrace, determined, in your red t-shirt. We laughed, but somehow it felt fitting. You were only two and a half years old, and we were still living on Splai, in the “block of flats with the gods,” where the Dâmbovița River flowed sadly through a canal lined with concrete walls.

Now you have reached the age I was that day. Much has changed in the meantime. I wonder what changes you will bring.

It is widely acknowledged that the future lies in the densification of urban living, in cities, of course. Ultimately, urban life is the most efficient, with shorter commutes and a direct correlation between size and diversity: the larger the city, the more opportunities it offers to all its residents – entertainment, culture, employment, education.

This is the allure of large cities. A metropolis can afford a myriad of establishments, a botanical garden, a university, an opera house, and an excellent public transportation system. However, a metro system is not financially viable for cities with less than a million inhabitants. It is a costly investment that requires a critical mass of users to ensure economic sustainability. As more people rely on public transportation, it becomes increasingly cost-effective. The tram serves as a prime example, being a traditional electric means of transport. If the number of passengers diminishes, the maintenance costs escalate, and neglect becomes more prevalent. If the threshold drops below a certain point, it becomes unaffordable, leading to a scenario where everyone resorts to private cars.

It is often said that a city functions as an efficient organism, but this statement holds true only when it is managed correctly. Ineffectual administration results in public distrust, corruption, political instability, and, ultimately, economic decline and poverty. It perpetuates a vicious cycle, giving rise to vulnerable segments of the population that depend heavily on local governance and become more susceptible to abuses.

Given this context, it is unsurprising that the level of aggression increases in direct proportion to the complexities citizens face when attempting to access basic services. That is why most cities consistently ranking in the top 10 for quality of life statistics are located in Switzerland and Germany, while Bucharest traditionally occupies a place in the lower half of the spectrum.

Vienna and Zurich have been vying for the top spot for years, cities where navigation is seamless and citizens have faith in their local authorities, who, in turn, treat them with respect and attentiveness. They serve as exemplars of good governance, often fostering citizen participation. Residents of various neighborhoods actively contribute to decision-making processes and the city’s overall functioning, alongside professionals, while administrative decisions are made transparently. In Bucharest, civic initiative groups emerged from conflicts of interest between municipal administrations and citizens, dating back to 2010.

As you assume the role of mayor in 2057, I hope you will strive to bring about positive change in Bucharest. Lead with integrity, inclusivity, and a vision for a city that places the well-being and aspirations of its residents at the forefront. Embrace participatory governance and transparency, working towards creating an environment where people can thrive, discover opportunities, and live fulfilled lives.

I have unwavering confidence in your ability to make a difference. Remember to lend an ear to the voices of the people, collaborate with experts, and exhibit courage in your decision-making. Bucharest possesses immense potential, and under your guidance, it has the opportunity to become a city that we can genuinely take pride in.

© Ștefan Tuchilă, ultimul Etaj

When the last major earthquake struck in 2027, you were 10 years old. The administration monumentally failed to cope with the disaster, resulting in a significant increase in casualties, similar to what happened during the Colectiv nightclub fire in 2015, two years before you were born, where more people died in hospitals than in the actual fire. Since then, Bucharest residents have learned, and civil society has organized itself better, getting involved in preparedness operations for diseases and response to earthquakes.

The 2020s were a turbulent decade: it began with the Covid-19 pandemic and continued with the rise of far-right movements, as if Europe had grown tired of the hard-won democracy in the East, gained just 30 years earlier. From France to Poland and from Hungary to Germany, many people’s expectations had been disappointed, and the new extremists flagrantly trampled upon the rights of minorities, women, and vulnerable groups. However, they eventually learned, albeit reluctantly after violent protests, that cities must first and foremost be communities: a city without people would not exist.

For a long time, our city had been renowned abroad for its unique dynamism, the opportunities it offered to everyone, the affordability of drinks, and the rich social life. It was like a paradise city, much like Brecht’s Mahagonny, “a place of pleasures where no one works, everyone drinks, plays, fights, and goes to prostitutes; all that matters is whether you can afford the services.”

Tolerance for different opinions and diverse lifestyles, as well as relative social security, declined over time as the city was increasingly mismanaged and temperatures rose. This was reflected in the numbers: after 1992, the illusion no longer held, and the population began to decline towards 1.8 million inhabitants.

The 30 years following the collapse of the totalitarian regime in which I grew up felt like an eternal transition. My generation aged, waiting for something that never happened. Back then, the streets were so crowded every day of the week that you would think no one was working in the office buildings constantly being constructed by real estate developers.

Unexpectedly, in 2020, the pandemic arrived and changed everything. Unfortunately, it is during challenging times and catastrophes that we truly learn and grow, not during easy situations. With each earthquake, fire, and pandemic, people learn to build safer, introduce safety and hygiene standards, and modernize infrastructure, rethinking urban regulations and adapting them to current life, much like they did in the Middle Ages, placing fountains at every important crossroads.

© Ștefan Tuchilă, ultimul Etaj

Slowly, the climate changed everywhere: in Bucharest, the average temperature increased by a few degrees, fueled by continuous traffic congestion and, especially, the “trimming” of trees. Once their cool shade was replaced by air conditioners dripping on the heads of passersby from April to October, making summers harder to bear, Bucharest residents became climate migrants, seeking refuge in the mountains for four months of the year. However, the suffocating flow of cars did not decrease because people understood something, but only after reaching a crisis: frustrated by the continuous traffic jam on the DN road, people from Prahova County started setting fire to large black cars with a “B” license plate. That’s why the Băicoi-Brașov tunnel was dug, and the Pitești-Sibiu highway was finally built, connecting Muntenia with Transylvania.

A city from which anyone can afford to escape the heat becomes semi-deserted for a third of the year – and suffocated by cars for the rest of the time. Many establishments cannot cope with this fluctuating influx and end up closing their doors forever, impoverishing the culinary landscape. You can no longer go to “the Chinese place on Occidentului Street,” “the Frog,” “the Turkish restaurant on Viilor Street,” or “the Russian spot”; you end up ordering everything online. But you didn’t go out to the city just for food, but for entertainment, to meet people. However, people stopped going out too since the pandemic. Along with the disappearance of restaurants, taverns vanish as well, and if you don’t go out anymore, another reason to stay in Bucharest disappears. Then you could stay in another city that offers you more.

Why struggle in a capital city that has been deteriorated by so many incompetent and greedy administrations, with insufficient parking spaces, buildings at risk of collapse, closed or overcrowded nurseries and schools, neglected parks overrun by concerts and festivals that terrorize entire neighborhoods with their decibels? For a while, people worked from home, then they realized that things wouldn’t change anytime soon and that it was preferable to move to a smaller city that, however, functioned better.

Understanding this, those who could, left for Cluj, Iași, or Constanța, where services were cheaper, green areas were closer, and they offered peace and tranquility. What’s the point of a “Green Village” for which you had to cross the city in infernal traffic? You spent hours in the car that you could have spent with your loved ones. And you arrived home completely aggressive – “so many hysterical people in traffic today!” You had become one of them yourself.

In the smaller city, your income might have been slightly lower – but everything was cheaper and more accessible – so practical! Traveling less and more thoughtfully, people brought home lifestyles that no longer fit the “more is more” and “the law is for fools” mentality of the 2010-2020 years. Adversity towards opulence, combined with new sanitary norms, gradually led to profound changes in urban living.

When the pandemic broke out and people were forced to stay in their homes during the first lockdown from March to May 2020, Bucharest residents began to discover their proximity. At that time, I was curating the Street Delivery event, which had been taking place for 15 years on Verona Street, which aimed to transform it into a green, pedestrian axis from east to west. Due to the new regulations, that year the event was divided into islands throughout the city, and its theme was called “ReSolutions.” Projects that proposed the improvement of the space around homes were awarded.

By autumn 2020, some of these small projects had grown, taking root and then being replicated in other neighborhoods. Gradually, flower beds and beehives appeared on the rooftops of many buildings, first around Cișmigiu Park and in the gardens of the Dorobanți neighborhood, then in Pantelimon and Militari – even though we were the only European capital where beekeeping was not encouraged, but explicitly prohibited. This was absurd because urban honey is actually cleaner than “rural” honey since bees can filter out pollutants but not pesticides from the environment. Paradoxically, some of the first guerilla gardeners were actually employees of the Parliament Palace, who had planted a small vegetable garden in its courtyard.

The pandemic in 2020 accelerated some changes that had already been underway for some time. Among them was the reconsideration of urban space. First, malls fell out of use, those large, rare places where people used to cram together – they reminded the population of the consumer frenzy that followed the poverty of the 1980s. In some neighborhoods, there were hardly any commercial spaces at all – that’s where the appearance of pop-up markets was supported, held for two or three days a week, like the one at the University corner where we used to go on Thursdays and Fridays, with you in the stroller and later on bicycles, to buy blackberries, quinces, and cheese.

Sidewalks were widened, and the importance of cars, which had reached a number equal to the population in 2021, diminished. They congested the streets from Monday to Friday and mysteriously disappeared on weekends. The ostentatious and heavy SUVs, which could block multiple parking spaces at once, went out of fashion. They had become status symbols that no one could afford to buy with their salaries. Wasting resources had become the mark of parvenus from bygone times. “Small is the new big,” every child knew by then, and children became more resourceful than their parents and grandparents, preferring experiences over material wealth.

Temporary pedestrianization was introduced: on many streets, car traffic was prohibited in the evenings, which encouraged local businesses in the neighborhoods. Gradually, people finally began to perceive public space as belonging to everyone, not to no one, so tall fences went out of style. A street with 3-meter fences became a road between battlements, not pleasant at all, and it made you wonder, “What important thing do they have to hide here?”

Then, a belt of greenhouses and community gardens grew around the city, which could be rented annually to grow vegetables close to home. Small streets shaded by pines and oaks became trendy again. It was easy to navigate through our city; signs and infographics were placed everywhere in the hope that tourists who once came for cheap drinks would return for the quality of services.

People understood that shade provided coolness, not air conditioners that heated the surroundings and wasted energy. Thus, buildings were equipped with facade blinds and brise soleil. Inspired by the Greek city model, city officials introduced the “Umbrella” program – a cheap solution that turned apartments into greenhouses and standardized facades, instead of the thermal insulation programs that had struggled to take off in the 2010-2020 period.

To decongest the streets and create socializing spaces close to home, ground floors of apartment buildings were transformed into neighborhood shops and parking spaces. Trees were planted on both sides of the streets, and small parks were created at every possible intersection, reclaiming spaces previously occupied by cars. Now you have access to green spaces on every street corner; there’s no need to travel to a park. Seniors and mothers with young children were the first to benefit from these improvements.

With the opening to the Greek city model, suitable for the arid climate of the steppe region where Bucharest is located, other lessons were learned from the Hellenic experience, where the capital clearly set the tone: Athens was already one of the most densely populated cities in Europe, growing from 4,000 inhabitants gathered around historical ruins in 1833 to 3 million in 2020.

To accommodate the wave of Greek immigrants from Asia Minor starting in 1920, the Athenians invented and endlessly replicated throughout the city the “polikatoikia,” a type of building with 4-7 floors and a simple concrete structure, which now represents the overwhelming majority of buildings in Greek cities. The initial constructions adhered to urban planning rules and were pleasant, with sufficiently high ceilings, 100 square meter apartments, and friendly balconies. However, after the 1960s, the quality of construction began to decline in favor of profit.

We hoped not to repeat the mistakes of Athenians: prioritizing the interests of real estate developers, ignoring urban development regulations, which led to the construction of buildings that were too close to each other and “face-to-face.” To make room for them, Athenians had demolished older, classical-style buildings.

But that was already happening here anyway, even in the “restituted” parks, now exploited for real estate purposes. Then, the almost identical reproduction of the same dull building model on every plot of land. The taller, the better! And it should be as cheap as possible! But the apartments themselves were expensive, large, residential, with an average size of 75 square meters, starting from 3 rooms upwards, contradicting the needs of Bucharest residents for smaller and more affordable housing. My generation had already made this mistake.

Only the fetishization of historical substance remained, the principle on which Athens had built its entire modern identity. Due to lack of interest and education, and because of the unclear property situation, Bucharest residents had neglected their heritage for decades – or what was left of it after the communist systematization and demolitions. And now they risked jumping to the opposite extreme, transforming the facades of the 1980s apartment blocks into fake Art Deco.

In essence, Bucharest had much in common with Athens, its older sister in every respect. But it lacked the sea. Our capital had emerged in the midst of the semi-arid Bărăgan Plain, on a fold of land eroded by the Dâmbovița River, as a marketplace at the crossroads of commercial routes between the Levant and Western Europe. The local climate had always been relatively harsh, with temperature extremes, even before the climate crisis, compared to most settlements in the region that were located “below the mountains” or closer to larger, navigable waters.

Over time, the city continued to grow, most significantly during the industrialization period when it tripled in size between 1912-1948, surpassing 1 million inhabitants. Then, it experienced another wave of growth after 1966, with the forced centralization by the communists, reaching over 2 million residents in 1992.

© Ștefan Tuchilă, ultimul Etaj

Like Athens, the city had developed without consistency, without harmony in the mix of architectural styles and forms, many of which contradicted each other from the moment they appeared (such as the traditional Neo-Romanian style with liberal modernism at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries). Growing rapidly and with changing administrations that didn’t manage to complete the projects they started, the city had been hit by various urban plans, all of which were initiated but never fully executed.

Thus, chaos and urban heterogeneity became ingrained here, reflected in the way architectural styles blend and details from “Little Paris” coexist with a little Moscow and a small Istanbul. Each person did as they saw fit, enclosing balconies, personalizing facades, erecting fences where it seemed convenient. It wasn’t until after the pandemic in 2020 that open balconies reappeared, after being used as storage spaces for so long. After all, the balcony is what provides shade to the sidewalks and facade and offers a semi-public space where you can interact with others – and during lockdown, without the risk of infection (at that time, it was called social distancing).

And the river, the ancient Dâmbovița, on whose banks the city was founded, became the absolute center of interest. In a competition organized by the Architects’ Association in 2020, the winning project proposed a series of bridges that moved the action from the city center directly onto the river, transforming the industrial canal-like banks hastily created in the 1980s into genuine sloping gardens.

Water became the essential theme of the capital: swimming pools, recreational areas, and especially drinking fountains are now everywhere! Today, nobody would buy bottled water from a store as we used to. Single-use plastic had become absurd, and the European Union had banned its use since 2019 to protect rivers and seas.

The city’s natural springs, such as Bucureștioara, were rediscovered. In parks, public toilets with water were reintroduced, converted into restaurants after the 1990s. With the new administration elected in 2020, everyone understood what a business private contracts for public toilets had been, inappropriately labeled as “eco.”

When the pandemic hit and people were required to stay at home during the first lockdown from March to May 2020, Bucharest residents began to discover their sense of proximity. At that time, I was curating the Street Delivery event, which had been taking place on Verona Street for 15 years. The event aimed to transform the street into a green pedestrian axis from east to west. However, due to the new regulations, the event that year was divided into islands throughout the city, and its theme was called “ReSolutions.” Projects that focused on improving the spaces around homes were awarded.

By the autumn of 2020, some of these small projects had flourished and started to spread to other neighborhoods. Gradually, rooftops of many buildings became adorned with layers of flowers and beehives, first around Cișmigiu Park and in the gardens of the Dorobanți neighborhood, and later in Pantelimon and Militari. Interestingly, Bucharest was the only European capital where beekeeping was not encouraged; in fact, it was explicitly prohibited. This was absurd because urban honey is actually cleaner than “rural” honey since bees can filter out pollutants but not pesticides from the environment. Paradoxically, some of the first guerilla gardeners were employees of the Parliament Palace, who had planted a small vegetable garden in its courtyard.

The pandemic in 2020 expedited changes that had been brewing for some time. One of these changes was the reconsideration of urban space. Malls, once crowded and reminiscent of the consumer frenzy that followed the poverty of the 1980s, fell out of favor. In some neighborhoods, commercial spaces were scarce. As a result, pop-up markets emerged, operating two or three days a week, such as the one near the University, where I used to go on Thursdays and Fridays with you in the stroller, and later on bicycles, to buy blackberries, quinces, and cheese.

Sidewalks were widened, and the importance of cars, which had reached a number equal to the population in 2021, diminished. They congested the streets from Monday to Friday and mysteriously disappeared on weekends. The ostentatious and heavy SUVs, which could block multiple parking spaces at once, went out of fashion. They had become status symbols that no one could afford to buy with their salaries. Wasting resources had become the mark of parvenus from bygone times. “Small is the new big,” every child knew by then, and children became more resourceful than their parents and grandparents, preferring experiences over material wealth.

Temporary pedestrianization was introduced: on many streets, car traffic was prohibited in the evenings, which encouraged local businesses in the neighborhoods. Gradually, people finally began to perceive public space as belonging to everyone, not to no one, so tall fences went out of style. A street with 3-meter fences became a road between battlements, not pleasant at all, and it made you wonder, “What important thing do they have to hide here?”

Then, a belt of greenhouses and community gardens grew around the city, which could be rented annually to grow vegetables close to home. Small streets shaded by pines and oaks became trendy again. It was easy to navigate through our city; signs and infographics were placed everywhere in the hope that tourists who once came for cheap drinks would return for the quality of services.

People understood that shade provided coolness, not air conditioners that heated the surroundings and wasted energy. Thus, buildings were equipped with facade blinds and brise soleil. Inspired by the Greek city model, city officials introduced the “Umbrella” program – a cheap solution that turned apartments into greenhouses and standardized facades, instead of the thermal insulation programs that had struggled to take off in the 2010-2020 period.

To decongest the streets and create socializing spaces close to home, ground floors of apartment buildings were transformed into neighborhood shops and parking spaces. Trees were planted on both sides of the streets, and small parks were created at every possible intersection, reclaiming spaces previously occupied by cars. Now you have access to green spaces on every street corner; there’s no need to travel to a park. Seniors and mothers with young children were the first to benefit from these improvements.

With the opening to the Greek city model, suitable for the arid climate of the steppe region where Bucharest is located, other lessons were learned from the Hellenic experience, where the capital clearly set the tone: Athens was already one of the most densely populated cities in Europe, growing from 4,000 inhabitants gathered around historical ruins in 1833 to 3 million in 2020.

To accommodate the wave of Greek immigrants from Asia Minor starting in 1920, the Athenians invented and endlessly replicated throughout the city the “polikatoikia,” a type of building with 4-7 floors and a simple concrete structure, which now represents the overwhelming majority of buildings in Greek cities. The initial constructions adhered to urban planning rules and were pleasant, with sufficiently high ceilings, 100 square meter apartments, and friendly balconies. However, after the 1960s, the quality of construction began to decline in favor of profit.

We hoped not to repeat the mistakes of Athenians: prioritizing the interests of real estate developers, ignoring urban development regulations, which led to the construction of buildings that were too close to each other and “face-to-face.” To make room for them, Athenians had demolished older, classical-style buildings.

But that was already happening here anyway, even in the “restituted” parks, now exploited for real estate purposes. Then, the almost identical reproduction of the same dull building model on every plot of land. The taller, the better! And it should be as cheap as possible! But the apartments themselves were expensive, large, residential, with an average size of 75 square meters, starting from 3 rooms upwards, contradicting the needs of Bucharest residents for smaller and more affordable housing. My generation had already made this mistake.

Only the fetishization of historical substance remained, the principle on which Athens had built its entire modern identity. Due to lack of interest and education, and because of the unclear property situation, Bucharest residents had neglected their heritage for decades – or what was left of it after the communist systematization and demolitions. And now they risked jumping to the opposite extreme, transforming the facades of the 1980s apartment blocks into fake Art Deco.

In essence, Bucharest had much in common with Athens, its older sister in every respect. But it lacked the sea. Our capital had emerged in the midst of the semi-arid Bărăgan Plain, on a fold of land eroded by the Dâmbovița River, as a marketplace at the crossroads of commercial routes between the Levant and Western Europe. The local climate had always been relatively harsh, with temperature extremes, even before the climate crisis, compared to most settlements in the region that were located “below the mountains” or closer to larger, navigable waters.

Over time, the city continued to grow, most significantly during the industrialization period when it tripled in size between 1912-1948, surpassing 1 million inhabitants. Then, it experienced another wave of growth after 1966, with the forced centralization by the communists, reaching over 2 million residents in 1992.

Like Athens, the city had developed without consistency, without harmony in the mix of architectural styles and forms, many of which contradicted each other from the moment they appeared (such as the traditional Neo-Romanian style with liberal modernism at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries). Growing rapidly and with changing administrations that didn’t manage to complete the projects they started, the city had been hit by various urban plans, all of which were initiated but never fully executed.

Thus, chaos and urban heterogeneity became ingrained here, reflected in the way architectural styles blend and details from “Little Paris” coexist with a little Moscow and a small Istanbul. Each person did as they saw fit, enclosing balconies, personalizing facades, erecting fences where it seemed convenient. It wasn’t until after the pandemic in 2020 that open balconies reappeared, after being used as storage spaces for so long. After all, the balcony is what provides shade to the sidewalks and facade and offers a semi-public space where you can interact with others – and during lockdown, without the risk of infection (at that time, it was called social distancing).

And the river, the ancient Dâmbovița, on whose banks the city was founded, became the absolute center of interest. In a competition organized by the Architects’ Association in 2020, the winning project proposed a series of bridges that moved the action from the city center directly onto the river, transforming the industrial canal-like banks hastily created in the 1980s into genuine sloping gardens.

Water became the essential theme of the capital: swimming pools, recreational areas, and especially drinking fountains are now everywhere! Today, nobody would buy bottled water from a store as we used to. Single-use plastic had become absurd, and the European Union had banned its use since 2019 to protect rivers and seas.

The city’s natural springs, such as Bucureștioara, were rediscovered. In parks, public toilets with water were reintroduced, converted into restaurants after the 1990s. With the new administration elected in 2020, everyone understood what a business private contracts for public toilets had been, inappropriately labeled as “eco.”

Now, Lake Herăstrău is clean, and regular swimming competitions are held there, culminating in the big April crossing, where 300 people swim from Pescăruș to the elegant pedestrian bridge under the railway overpass.

This is how the reorganization of neighborhoods began: there are no more purely residential neighborhoods like Bercenii or strictly corporate neighborhoods like Pipera, where poor people had to commute daily. Different functions were introduced in all neighborhoods, such as parks, swimming pools, sports arenas, and summer gardens that also serve as open-air cinemas. Flexible part-time work schedules became popular, prioritizing office spaces for families and individuals who cannot work from home.

With great success, after the elections in 2024, the previous sector divisions in the form of a pizza were replaced by 20 metropolitan districts. As smaller administrative units, it became easier for the mayors to take responsibility and address local issues. There are no longer situations like before, where you had the Unirii Square in the heart of the city and the Livezilor Alley in Ferentari in the same sector, with the latter only making the news around election time.

The administration itself has completely changed. Mayors regularly walk the streets during peak hours and in all weather conditions, using public transportation, walking, or cycling, without drivers or security, to monitor the well-being of their city. They have learned that you can’t truly understand the issues of your city if you live outside of it and only traverse it in an SUV with a driver and security, as many did in the early decades of the century.

Moreover, the number of security guards has significantly decreased. The era of snobby secretaries, bodyguards who triage emergency cases, and security guards at pharmacies and grocery stores is long gone. Public service has become a respectable and respectful matter: being a public servant means serving the citizens well, not exercising control or abusing them. When good services are provided, everyone benefits.

Education underwent reform as well. Initially, due to the lack of space resulting from new sanitary regulations (pandemic!), school hours started to be held in museums, greenhouses, parks, gardens, and swimming pools. Seeing the excellent results and the need for additional staff, now with much smaller classes of 10-15 children, the changes continued. In addition to traditional teachers, professionals from different fields started teaching for a few hours a week. Working in the public service is now trendy.

The old school buildings have become community centers, with public spaces for residents, mainly used by young people but also open to seniors, with libraries and multifunctional halls. Regular earthquake response training takes place here: people have learned from the last major earthquake that hope lies in civil society, not the system.

Despite the climatic and administrative complications, or perhaps precisely because of them, Bucharest has grown into a pleasant city with diverse public spaces, realizing its significant potential.

Now let’s see what you will do with it. Good luck!

Frumusețea unui oraș. București. Mița Biciclista.

Intre 18.5-2.7.2023 a avut loc o expoziție despre frumusețea Parisului, care marchează primul sezon cultural la Casa Mița Biciclista din piața Amzei. La invitația ARCEN am curatoriat in deschiderea ei o mica expoziție despre frumusețea Bucureștiului.

Link despre expo pe site-ul Zeppelin.

Detalii despre conținut urmează in josul paginii, iar la final gasiti un link catre emisiunea despre Frumusetea Bucurestiului.

Extras din textul curatorial:

DE CE BUCUREȘTI?

Cum e București? Un oraș în mijlocul câmpiei, cu oameni grăbiți. Mereu in șantier, orașul compromisurilor, orașul târguielii, așa a fost mereu, prin natura așezării sale la întretăierea unor vechi rute negustorești între Levant și Apus. Cand întrebi pe cineva de ce s-a hotarat pentru București, îți va spune ca “pentru cineva”. Pentru oamenii sai. Pentru dinamica lor specială.

Cum este București? E orașul care nu-ți mai da drumul. Pleci – și revii mereu.

Ca să înțelegem orașul, îl vom lua pe îndelete, explorand cele șase teme care-l compun.

- Texturile:

Fiecare oraș are texturile sale, imaginile, mirosurile, ceea ce putem atinge, lumina pe care o simțim pe piele.

- Grădinile și verdele:

Cel mai bun moment al orașului este probabil primăvara, cu teii în floare. Sau în septembrie, cu castanele căzând pe trotuar, toamna blândă care durează până târziu în octombrie. Văzut de sus, orașul arată că o grădină zăpăcită. Chiar și în cele mai aride cartiere se zbate verdele. Vara e prea cald și iarna e prea frig.

Dar serile de vară când suntem cu toții pe afară? Sau iarna când zăpadă amuțește în fine toate sunetele traficului și gri-ul.

Dacă ar fi să dorim un singur lucru orașului, e puțină umbră. Și liniștea care vine odată cu umbra.

- Dâmbovița:

Capitala noastră a apărut în mijlocul Bărăganului semiarid, într-un pliu al terenului erodat de Dâmbovița. Clima a fost aici mereu mai aspră, cu extreme termice, dacă e să comparăm cu majoritatea așezărilor din zonă, care se află “sub munte” sau la o apă mai mare, navigabilă. Dâmbovița în sud și salba de lacuri a Colentinei în nord, cu bucureștenii forfotind între cele două. Ar trebui să le purtăm mai multă grijă.

- Moștenirea culturală:

Crescând rapid și cu administrații schimbătoare, care n-au apucat niciodată să termine de realizat proiectele demarate, orașul a fost lovit în timp de diverse sistematizări, toate începute și neduse la bun sfârșit. Așa s-au împământenit haosul, heterogenitatea urbană, reflectate în felul în care se amestecă stilurile arhitecturale și conviețuiesc bucăți care par luate din Paris, Moscova sau Istanbul. Fiecare face aici cum îl taie capul, închide balcoane, personalizează fațade, trage un gard cât mai înalt pe unde i se pare avenit.

Astfel orașul s-a dezvoltat neunitar, deloc armonios în învălmășeala de stiluri și forme – multe din ele contrazicandu-se încă de la apariție (cum ar fi neoromânescul tradițional cu modernismul liberal la final de secol XIX și început de sec. XX).

- Cartierele și identitatea lor:

Cartierele vechi și liniștite, Cotroceni, Icoanei, Armeneasca, cu străzi întortocheate, cu copaci care asigură destulă umbră vara și frâng crivățul iarna, creând un microclimat mai blând, sunt foarte apreciate pentru scara lor umană. Apoi cartierele de blocuri: Balta Alba, Drumul Taberei, Obor, Floreasca, Tei, Pantelimon, Militari, Rahova, Ferentari, Berceni, Calea Moșilor (partea nouă), Vitan, Decebal, Calea Grivitei, Chibrit.

În București exista migrația zilnică nord-sud: mulți dorm în sud, unde densitatea populației e mult mai mare, și lucrează în nord, unde s-au construit birourile. Pleci dimineața dintr-un cartier dormitor ca Bercenii și lucrezi toată ziua într-un cartier-corporatist că Pipera, ca să te întorci seara.

Bucureștenii, mereu în mașini, claxonându-și drumul prin orașul sufocat.

- Ospitalitate / Oameni:

Cum sunt bucureștenii? După vechime, de trei feluri: Localnici, dintotdeauna aici, foarte puțini și liniștiți până la blazare. Orașul lor e cel de sub agitația zilnică, cel în care se plimba când pleacă toți ceilalți. Apoi, cei semi-permanenți, care vin aici “la pomul lăudat” și pleacă în weekend și de sărbători. Ei sunt cei mai mulți – însă ei nu văd decât orașul apăsător și aparent smucit, luni-vineri, ambuteiaje și nervi, pe goană. Apoi musafirii, mereu bineveniți, indiferent de unde vin și ce așteaptă să găsească aici.

Vă invităm să descoperiți urme din toate acestea în expoziție: de la imaginile cu orașul vechi ale lui Alex Gâlmeanu, dar și unele de acum, ale lui Andrei Bîrsan, Alberto Groșescu și ale Anei Vasile, vederi de sus de pe acoperișuri ale lui Ștefan Tuchilă, vestitul accident din piața Amzei al lui Roman Tolici, precum și pictura cu praf din Berceni a lui Nicolae Comănescu, dar și plantele sălbatice ale Irinei Neacșu. Plăcuțele cu poezii ale lui Mugur Grosu. O mică colecție de obiecte care reprezintă Bucureștiul și părțile lui bune, aromele și texturile. O piatră cubică, o coroană de salcie din Dâmbovița. O eugenie și o minge de pe un acoperiș ale lui Zoltan Bela. Coconul lui Dumitru Gorzo. O serie de texte care povestesc orașul, prin ochii câtorva dintre oamenii săi.

Vă invităm să lăsați și voi un rând sau un obiect aici.

Despre expoziție am vorbit si la TVR Cultural în emisiunea “Intrare libera” a lui Marius Constantinescu – ale cărui texte despre grădinile orașului sunt de găsit si pe pereții casei Miței. Ceilalti invitați au fost Edmond Niculușcă, arh. Vera Dobrescu, specialist în peisagistică (via Zoom), Dia Radu și Matei Martin – #IntrareLibera de vineri. Regizori Anca Lazarescu și Micu Aziza.

Masa

Într-o zi o să am în fine masa aia mare la care o să se adune lumea dragă.

În timp au fost câteva mese la care îmi găseam locul.

Masa florentină de la bunica – o masă lungă și aproape neagră, cu desenele mele sub sticlă – cam rece sticla aia – însă se punea fața deasupra, ca un ștergar brodat – aici veneau toți cu povesti, cu frici, cu zâmbete, se întindeau la cafele și dulcețuri – până la urmă se găseau soluții pentru orice. Nu mai e casa aia de o vreme și masa e acum înghesuită într-un apartament.

Masa rotundă cu picior hexagonal de la bunicii din partea mamei, unde mâncai sub privirea blândă și amuzată a străbunicului din tablou. Acolo erau șnițele și preiselbeeren. Și afară la geam atârna o căsuță de păsări făcută de bunicul, mereu asaltată de sticleți gălăgioși.

Masa din parterul întunecos al străbunicii, unde te simțeai mereu ca la jour fixe și stăteai cu spatele drept și ascultai radio și poveștile ei cu zeppeline zburând pe cer, dar și cu morții de la cutremurele și bombardamentele trăite.

Masa alor mei, tot rotundă, luminoasă, odată veselă, însă mereu cumva tensionată și reprezentativă; în ultima vreme doar locul certurilor și al fețelor lungi, peste care se aude constant agitația, “mai vreți supă? vreți o cafea? mai vreți cartofi? aduc prăjitură?”

Parcă nu ne mai auzim demult.

Masa din garsoniera mea de la final de facultate, unde se adunau aproape zilnic prieteni – unii nu mâncau porc, alta era vegetariană, se dezbăteau aici toate subiectele pământului, jucam jocul ăla cu “cine sunt eu?” cu bilețele în frunte. Cel mai bine era că aici se rezolvau probleme și conflicte, ziceau ei. Era loc pentru toți. Eu cică găteam constant pe margine, cu un pahar de roșu într-o mâna și cu pauze de țigară la fereastră.

A fost o vreme masa din Zürich, care sâmbăta era mereu plină cu bunătăți și câteva ziare pe care le aduceam când veneam de la cai, indiferent de vreme. Pe la 11 când se trezea și el, pe mine deja ma lua somnul. Pe după masă veneau prietenii, găteam, poveștile lor se împleteau cu vinul roșu și ultimele idei de proiecte și expoziții.

Nu a fost să fie masa din apartamentul amenajat cu atâta drag în Mântuleasa. Mare, albă, mereu plină – dar venită într-un moment în care nu mai eram noi – eram deja fiecare pentru el.

Acum masa mea e mică, încăpem maxim doi și-o pisică.

Într-o bună zi o să am masa mea mare, cu copii și cu prieteni în jur,

unde se poate așeza oricine vine cu drag și fără țâfnă.

București cotidian. Viața în 7 cartiere, 2020

București cotidian. Viața în 7 cartiere, 2020, era o serie de emisiuni care explorau viața de zi cu zi în diverse cartiere ale Bucureștiului. Această serie a luat naștere în contextul izolării în timpul pandemiei și a schimbării temei inițiale către urgența climatică. Pe durata lunilor de izolare, oamenii au petrecut mult timp acasă și au fost limitați în deplasarea în zonele cunoscute din centrul orașului. Astfel, s-a evidențiat importanța îmbunătățirii vieții cotidiene la nivel de proximitate, în cartierele orașului.

Emisiunile explorează diferite cartiere și aduc în prim-plan nevoile specifice ale acestora. Dezbaterile implică specialiști din diverse domenii, cum ar fi sociologi, strategi, urbanisti, dar și persoane care trăiesc în aceste cartiere. Fiecare emisiune este ghidată de un riveran local, care oferă informații și perspectiva sa asupra zonei respective.

Printre cartierele abordate se numără

Icoanei, (Centrul și centrele),

Cișmigiu și Poezia Vecinătăților,

Uranus Rahova – Înapoi în viitor,

Kiseleff 1 Mai, Parc și Muzee,

Grivița Giulești – Ateliere și cinematografe, și

Vatra Luminoasă – Cartier 2.0.

Scopul emisiunilor este de a evidenția nevoile și potențialul fiecărui cartier, de a promova implicarea comunității și de a contribui la dezvoltarea urbană durabilă și la îmbunătățirea calității vieții în toate cartierele orașului București.

Această serie de emisiuni a facut parte din evenimentul Street Delivery București, organizat de Fundația Cărturești și Ordinul Arhitecților din România, susținută prin proiectul strategic al OAR finanțat prin #TimbrulDeArhitectură.

“Din Cotroceni în Ferentari și din Titan în Dorobanți, fiecare cartier are nevoi, are locuri “bune” și “rele”, are oamenii săi. Explorăm, împreună cu 3 invitați pricepuți din diferite domenii – strateg, psihiatră, brancardier, avocată, sociolog, croitoreasă, stylist, urbanistă, taximetrist. La fiecare cartier, ne îndrumă un riveran.”

Ce vrem:

- Un oraș mai plăcut în toate cartierele, nu mutarea centrului de greutate într-o zona care funcționează acum. Vrem să funcționeze fiecare cartier, să trăiești bine în el, să fie siguranță, sănătate, cultură peste tot, nu doar in centru si 100% susținut din bugetul de stat.

- Vrem walkability, un oraș in care sa te plimbi cu drag, nu pietonalizare, care e in sine o capcana, omorând magazinele și, odată cu ele, fluxul de pietoni.

- Politici publice, program oficial susținut de primărie. Odată cu molima nu trece și urgența. Vrem siguranță publică și sănătate publică. Designul e doar un instrument.

Siguranță, confort, sănătate publică, cultură – nu se exclud, ci se sprijină reciproc. Direcția de azi e inevitabila. Covid doar a accelerat ceva care oricum trebuia să se întâmple. - Dialogul cu societatea civila. De salutat că primăria a început sa asculte de organizații ale societății civile, OAR demult luptă pt îmbunătățirea calității vieții urbane, ideea e bună, dar alegerea zonelor încă nu e ideala și riscă să genereze o opoziție vehementă-> Cum facem ca inițiativa bună să fie susținută de o dorința legitimă a locuitorilor?

- Planul de mobilitate. Calmarea traficului, reducerea, nu desființarea lui: aprovizionarea și riveranii sunt tot trafic. În weekend centrul e chiar plăcut. Doar în weekend însă, ar fi deci păcat să li se ia tocmai asta. Iar traficul principal e generat dimineata de miscarea dinspre cartierele-dormitor din sud catre zona de birouri din nord.

Cartea Bucuresti Sud.