2013, November 24. We met again by chance in some bar. We danced like crazy, almost like that first time when you whirled me around, then suddenly lost your balance and let go and I almost landed on my skull.

Outside on the sidewalk, your dreamy smile, “Where should we go now. Somewhere nice.”

“We could go to my place, this time“, I said. “But it’s still under construction, I don’t live there yet.” Let’s.

First time I got to sleep here, on a huge towel in the middle of the room, the silhouette of furniture against the wall, covered in some old sheets. That foggy morning. Housewarming.

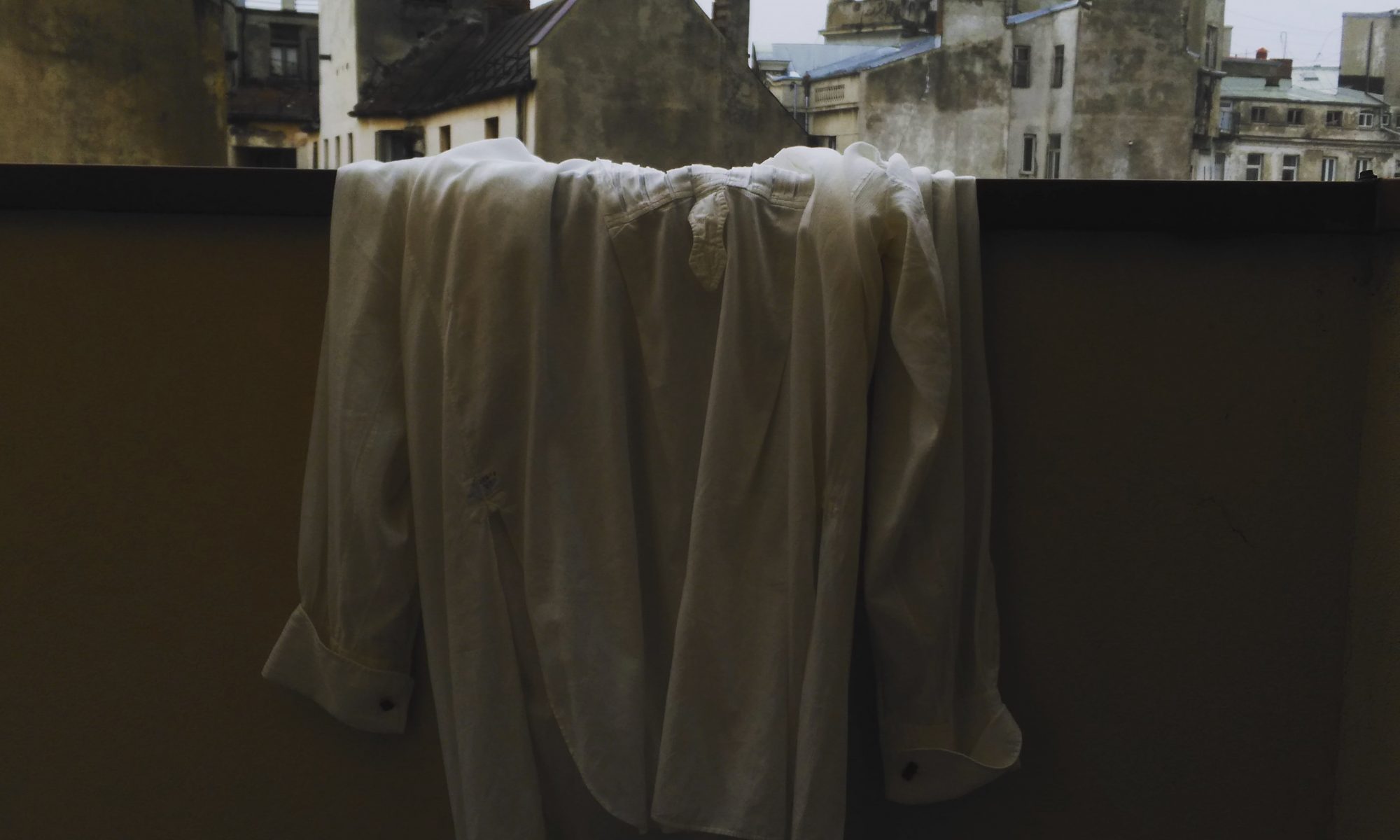

Taking off/ White Shirt #1

1999, November 22, I left Bucharest.

Excited: I would go to Germany on an Erasmus year. As sweet revenge for having failed the first attempt at high school admission 2 years earlier! Goodbye home of my quarrelsome teenage years, goodbye to all boundaries! Hello world!

I was going to travel and I would discover and I would love and it will all be worth it.

On my road, I shed so many skins. For every skin, I’ll post a shirt (and a memory) – to be found in this link. Come along.

The missed flight

December 31st, a few years ago, I’m about to fly back to Zürich where I was living at the time. Had booked it long in advance and was thus able to enjoy both a family Christmas in Bucharest – and a New Year’s Eve with friends there – and go skiing the morning after!

So I’m at the airport and check in 3 hours prior to the flight! Small luggage – checked. I’m sitting in the duty free area, reading and listening to the announces. The little Omega watch that once belonged to great grandma is slowly ticking the passing time away. 2,5 hours to go, 2 hours, one and a half, one hour: Nothing about Zürich or a Swiss flight. Half an hour to go, I go to the boarding area to inquire about the whereabouts of my flight.

Aaaand there it says, “GATE CLOSED”. One person is still at the counter, I rush towards them, “Hey, where is everybody?

“You are Miss Hasnas.” – Yes.

“We have just unloaded your luggage.” – What?! Please, don’t, I have to be there tonight! There’s still 30′ till flight time, how could you?!”

“We-ell, miss, there was hardly anyone on this flight, so we closed a bit early. But we announced it on the speakers several times.”

And then I see it. My watch is 8 minutes slow! The speakers in my duty free area were probably broken. The… “Please, the plane did not take off yet, I can see it from here, the door’s open – you have to get me on that plane, sir!”

“Nothing I can do now. It’s the last day of the year, ma’am.”

“But I have to be there tonight…”

I burst into tears. The ground staff kindly invites me to book another plane!! No refund for the early take off!

The flight takes off without me. Desperate to get on a plane, I call dad.

***

Dad walks with me from one counter to the next. Any combination we can use to get me to Zürich tonight?

In the end, it’s Air France, 850€, through Munich. I get there with a tremendous headache, but on time, after 14 hours on the road. Could almost have flown to Mexico in the meantime and for that amount of money. The headache makes me skip the New Year’s Eve party. The mere thought of champagne…The next morning we leave for the mountains.

It was the only time I flew on a plane with more crew than people on board. And I still feel ashamed when I think of it to this day.

Trauma (RO)

Când mă gândesc înapoi la nașterea lui Luca și zilele acelea de noiembrie petrecute în spitalul Bucur, mă cuprinde o tristețe uriașă – și un fel de greață dezarmantă. Au trecut 4 luni de atunci și îmi fac curaj să scriu, ca să trec odată peste episodul ăsta.

Pregatiri. Tensiune.

Cu doctorița mea preferată, în care am încredere și care mă știe de când aveam 17 ani, am stabilit tot ce se putea stabili dinainte: am convenit că aș vrea să nasc natural (la cât sport fac, n-ar trebui să fie o problema), am pus în calendar termenele de consultație, ecografiile fetale morfologice, analize de sânge.

Mi-a recomandat cursul de puericultură.

Următorul punct – unde să nasc? Am fost împreună, ca viitori părinți, și ne-am uitat la o clinică privată. Apoi la maternitatea de stat. Diferența în costuri: minim 2’000€. Ca impresie, maternitatea Bucur părea serioasă, avea un aer heavy-duty, nu mult mai ponosită decât clinica privată, excepție făcând sala de așteptare de la parter. În rest, poate pentru că era o duminica după-amiaza liniștită, totul părea în ordine. Asta m-a convins: doctorița “mea” e de acolo, va fi în largul ei cu personalul, maternitatea e aproape de noi și Andrei va putea merge ușor acasă, fără să traverseze orașul petrecând ore în sir în trafic. În fond, nu în calitatea brioșelor din cafeneaua spitalului se măsoară calitatea serviciilor acestuia, nu? Iar dacă e să iasă cu complicații, în final tot la spital ajungi. Să mergem pe siguranță, deci.

Cred că am mers cu bicicleta până în luna a 5a. Vara a trecut fară mare bătaie de cap, am mers la înot până în ultima săptămână dinainte de naștere, am făcut regulat yoga prenatală, ca să mă mențin în forma și să mă pregătesc pe cât posibil. Mi-am văzut prietenii, am făcut lucruri frumoase împreună, m-am obișnuit treptat cu corpul ăsta nou, mare și umflat, apoi cu mișcările bebelușului. Pe la jumatea sarcinii, specialistul în ecografie fetală care fusese atât de drăguț cu noi a murit. Una din ecografii, precum și testul Harmony (de sânge, pentru a detecta Down-Syndrome, fără amniocenteza) l-am făcut în Germania, unde toată excursia până acolo plus consultația plus încă câteva zile de sejur au costat mai puțin decât cei 1’000€, cât ar fi costat testul[1] aici.

Mi-am luat vitaminele, am citit literatură, am pus întrebările la curs, am căpătat răspunsurile, am așteptat ziua cea mare. În ultimele săptămâni, zilele parcă se târau. Știam deja că vă fi băiețel, că vă fi mare, că se vă naște probabil la început de noiembrie sau chiar sfârșit de octombrie. Priveam înainte cu încredere, parca mă împrietenisem cu graviditatea asta, chiar dacă la început îmi picase greu.

Vine săptămâna 40 și odată cu ea niște migrene teribile, plus tensiune ridicată. Colul lung și închis că-n prima zi, mult așteptatele contracții ioc, așa că stabilim împreună cu doamna doctor un termen limită: dacă nu se întâmplă nimic până joi, 2.11., cezariană. M-am întristat puțin, parca “nu reușisem” ceva ce le iese atâtor alte femei, dar nu e cazul să faci pe eroina când riști sănătatea fătului cu tensiunea. În fond, și eu m-am născut prin cezariană – și mama nu e o bleagă.

Încă un drum pe la camera de gardă cu 2 zile înainte, tot din cauză de tensiune și migrene – parcă îmi pulsa un ochi de durere – și concluzia e clară. Joi, 2.11, la 6 dimineața, ne prezentam la cezariană.

În seara dinainte am lucrat până după 10, eram agitată, să termin la timp o evaluare și să mă distrag puțin, dacă tot nu pot dormi. Motanul casei mi-a simțit și el starea, tot dădea târcoale mesei de lucru aiurea. Nici nu le-am mai spus alor mei, ca să nu se agite și ei. Am convenit că Andrei îi sună de cum intru în operație.

Ziua cea mare. Joi. Zâmbetul.

Am plecat spre spital la 5.30 dimineața, pe întuneric, cu fluturi în stomac: azi o să-mi văd bebelușul! Da, o să “mă taie”, dar o să văd bebelușul, până la urmă au mai trecut atâtea alte femei prin asta! Aveam totul la noi: geanta cu hainele mele, geanta mica cu haine și scutece pentru el, un bax de sticle de apă de jumătate de litru, cum s-a cerut. Sperasem până în ultima clipa că poate se rupe apa sau se mișcă ceva, dar copilul mișcă din ce în ce mai puțin. Am aflat ulterior că nu mai avea loc să se miște, fiind atât de mare. Și că nu ar fi ieșit nicicum “pe jos”, cum nu ieșisem nici eu, nici bunicul și frații lui, decât cu mari complicații, în cazul lor.

La camera de gardă, o muiere plictisită și prost dispusă a lătrat la mine că ce vin la ora asta. Așa mi s-a spus, pentru a pregăti totul până în ora 9, când voi naște. După vreo 45 de minute în care nu s-a întâmplat nimic, dar Andrei a trebuit să aștepte pe hol, a venit o doctorița tânără, care era de gardă. A completat plictisit-drăguță formularul, în timp ce muierea plictisită se slugărnicea pe lângă ea, încercând să o entuziasmeze pentru niște bârfe. Vream apă, aveam frisoane, Andrei stătea degeaba pe cealaltă parte a ușii, în hol, aici nu se mai întâmplă nimic, în afara de lătratul ocazional al asistentei către mine. Mi-a scris cu un marker gros codul pe cardul de sănătate, fără să întrebe. Mă întrebam cine s-o crede femeia asta, încât să se poarte așa necioplit. Poate a avut o gardă grea, dar eu m-am purtat frumos și nu e cazul să latre așa la mine.

După încă o oră, m-au trimis într-o cămăruță pe hol să mă schimb. Aveam pregătită o cămașă mare cu nasturi, care însă părea deodată foarte scurta și parca mă lasă despuiată pentru drumurile acelea interminabile pe holuri, pe lângă portar și alti oameni așteptând. Andrei venea după mine, cărând geanta – unde trebuia pusă, nu știam ce trebuie făcut, întrebam. “O să aflați la timpul potrivit”, lătra cineva.

Rază de soare: vine doamna doctor, caldă și zâmbitoare. Mă duce într-un salon în care alta femeie, mare și blândă, așteaptă să nască în fine. De ieri are contracții și tare și-ar dori să fie operata și să îi lege doctorul trompele, că e de la țară, mai are 3 copii mari din alta căsătorie, chiar nu mai poate face acum încă unul. Poate găsește un doctor înțelegător?

După jumătate de oră, pasul următor: merg în alta cameră, e monitorizată sarcina, se pare că totuși am niște contracții inegale, vagi. 2 asistente drăguțe glumesc pe seama aparatelor, dna doctor îmi explică ce urmează ca procedura. Se pregătește sala de operații.

Vine momentul. Îi spun lui Andrei la telefon că acum intru în sală, el mă întreabă dacă are oare timp să ducă un pisoi abandonat la veterinar, eu îi spun că nu știu, dar să fie acolo când ies, el urmează să îi sune pe ai mei.

La ușa sălii, pun telefonul în sacoșă, nu știu ce să fac cu sacoșa, dar e ok, din sală vine muzică și o atmosferă proaspătă, aici o să nasc, ce alegere bună, curând voi cunoaște în fine bebelușul pe care îl car în mine de atâta timp.

Iese o infirmieră cu o lamă și-un castronaș în mână și întreabă dacă sunt rasă jos. Da, epilată chiar. “Să văd daca e bine”. Vede, e ok, nu spune nimic, pleacă. Intru în sală, lumina verde, muzică buna, echipă zâmbitoare, sunt vreo 7 femei.

Vine anestezista, se prezintă, îmi explică cum vă face rahianestezia, socotește dozajul – “mai mult, că e atletică”. Mă întinde pe masă, îmi pune sonda, totul e “comfortably numb”.

În jur se aude conversația în surdină a echipei, muzică buna, nu miroase a nimic special. Prima mea operație!

Începem, mă gândesc. Mă uitam în tavan și la lumină, știam de la prietene cam cum ar trebui să fie, așteptam să simt ceva, fizic sau emoțional. Durează; aud mormăieli că trebuie mai mult. Mă întreb dacă fac totul bine. Ce aș putea să fac? La un moment dat, am simțit cum mi se mișcă bazinul de colo-colo, atât de tare au trebuit să tragă. Mai trece ceva timp, în care visam cum o să mă joc în fine cu bebelușul, când ajungem acasă, după toate astea – și gata: mi-l aduce deodată și mi-l arată: ochi de chinez, bebelușul râde, nu plânge, ce mă bucur, e de-al meu! Apoi îl duce de acolo.

După operație

Vin brancardierii, mă duc în salon la reanimare, mă mută cu pătură pe alt pat. O să înceapă să doară curând, zice cineva. Eu vitează în continuare, mi se pune branula ce o fi în ea?

Peste o oră e adusa următoarea cezariană. Cineva mi-aduce și geanta, cu telefonul, vorbesc cu Andrei, “ți-a adus bebelușul?” nu încă, nu prea știu ce să spun. Suntem trei într-un salon minuscul. Aveam să constat că e unul bun: în alt salon sunt câte 5 sau mai multe femei. Dar sunt peste 28 de grade în cameră. Geamul trebuie să rămână închis, “să nu se facă curent”. Căldură nu se poate regla.

Ziua trece încet, sunt semi-amorțită. Precis diseară voi vedea bebelușul.

Seara însă e prea târziu, nu mai aduce nimeni bebelușii la ușa neonatologiei de la etaj să ni-i arate. Nici pe Luca. Macar i l-au arătat lui Andrei, care mi-a trimis poza lui pe telefon. Spre seară ne dezmeticim încet, toate lăuzele, apoi vine doza de medicamente în branulă. Dorm. Sunt lăuză. Corpul se simte străin. Mâine e ziua cea mare în care voi tine în brațe bebelușul.

E noaptea în care dorm cel mai bine din toate ce au urmat în spital, probabil încrezătoare și îmbuibată cu diverse substanțe.

Ziua 2. Vineri. Urina.

Mă dezmeticesc dimineața devreme, cred că e 6. Se aprinde lumina, foiesc infirmiere și asistente, eu nu știu să le deosebesc. Azi văd bebelușul, în fine! Cum o arăta?

Celelalte tipe din salon sunt ok, una are unghii lungi și false, a născut cu o zi înaintea mea, cealaltă e miniona și vlăguită. Prima e îmbrăcată în negru și roz, cealaltă în vernil. Parcă și ochii lor sunt tot așa. Peste două ore vine o infirmieră să ne ajute să ne îmbracăm, “mobilizăm”. E atât de cald încât simpla idee să mă îmbrac în ceva care o să se lipească de mine ca la tropice mi se pare respingătoare. Ceva mi se prelinge între picioare, dar pare să fie “monitorizat”, deci sub control. Toată lumea are sondă, că nu putem merge încă la toaletă. Știam că te refaci mai greu după cezariană, iar asta e parte din refacere. Să ne mobilizăm. Asistenta spune, “daca vă mobilizați, în 2 ore vă dam bebelușul.”

Într-o cămașă bleu-gri-guguștiuc, pornesc pe hol ca un soldățel cuminte, cu punga de urină în mână, ținându-mă de pereți întăi, apoi încet-încet până la capătul holului, îmi pare că am mers până la Predeal pe jos și mă întreb daca mai am energie să mă întorc. Se cam învârte totul cu mine, dar – în 2 ore îmi da bebelușul în brațe daca mă mobilizez. Constat că burta mea e cam la fel de mare că pe când era copilul înăuntru… O să mai dureze ceva…

Mă întorc și mă las încet pe pat. 2 ore. Parcă mă jenează sonda.

Povestea se tot repetă până seara: treptat-treptat mă descurc mai bine, merg din ce în ce mai repede, urc și 2-3 trepte, ca să arat că pot. Nimeni nu-mi spune că de fapt nu mai sunt locuri azi în rezerve și oricum ar rămâne să mă mut abia mâine. Când văd bebelușul? Așteptați, vă mai mobilizați…Ce o fi făcând Luca în timpul asta? Doarme probabil. Cum o fi el? Dorm și eu. Timpul se târaște.

Când întreb o femeie în halat cu o față de nevăstuică, “când pot vedea bebelușul?”, îmi raspunde, “când va fi cazul”.

“Dar asistenta a spus că peste 2 ore, dacă mă mobilizez…”

“Infirmiera, vrei să spui!! Asistentă sunt doar eu!” latră ea la mine cu o privire de parcă i-am insultat neamul întreg. Nu mai spun nimic și aștept.

Andrei trece să mă vadă; ai mei toți vor să știe cum e bebelușul. La mine se instaurează încet un sentiment de jenă, de vinovăție. Nu l-am văzut nici până acum decât în poza de pe telefon, la care mă tot uit încercând să ghicesc ceva. Trimit poza tuturor. “Când să te vizitam?” întreabă ei. Nu stiu… Stai întăi să primesc odată copilul în brațe.

Se lasă noaptea, se schimbă personalul iar. Iar întreb, iar nimic. Mâine, spune o asistentă voinică și hotărâtă. Dorm. Mâine în fine voi ține în brațe bebelușul născut ieri…

În toiul nopții vine garda: se aprinde brusc lumina, intra o doctorita slabă cu buze strânse, un doctor înalt și grizonat, urmați de un cârd de asistente și infirmiere foarte atente la ei. Ajung la mine și dezbat ce e de făcut: de atâta mișcare, mi s-a colorat ușor urina din punga sondei. Asistenta voinica și drăguță așteaptă verdictul: daca să mă curețe cu betadină sau apa oxigenată, pentru a se vedea ce e cu sonda. Cinci capete dezbat privind la mine între picioare la 3 dimineața. Eu întreb când o să văd bebelușul.

Asistenta dă în fine cu apă oxigenată, dar trece puțin mai tare peste o labie și eu tresar. “Ce te smiorcăi?!” latră doctorița. Rămân uimită de asemenea ton. Tocmai eu, care am mărșăluit toată după-masa pe hol, indiferent cât durea, ca să văd bebelușul “peste 2 ore” care s-au lungit iar până mâine? “Am tresărit, atâta tot.” Doctorița îmi ține o lungă pledoarie răstită despre cum a născut ea 2 copii și nu s-a smiorcăit niciodată.

Între timp, îmi schimba sonda pe viu, trăgând și punând apoi una noua – de ce alta? Când puteam să mă duc între timp la toaleta bine-mersi. Probabil de supărare, o înfige atât de tare, încât mă rănește de-a binelea. Mai mult sânge în urină. Monitorizăm. Încep să nu mă simt bine, dar mă agăț de amintirea zâmbetului din sala de operație. Bebelușul meu.

A treia zi. Sâmbătă. Sânge.

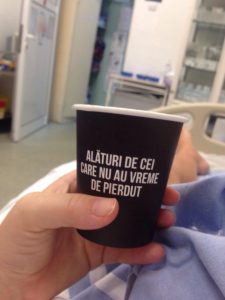

Mă chinui să dorm, mă simt vinovata și neputincioasa, mă trezesc, același ritual. Când pot să văd în fine copilul? Rând pe rând, fetele din salon sunt mutate în rezerve, rămân singură, sunt aduse “cezariene” noi. Asistenta drăguță mi-aduce o cafea.

Trece tata, care se amuză povestind cum i-a reparat o unealtă portarului și a fost lăsat să intre fără mari întrebări. Deși e weekend, deci program de vizitare de la 10 dimineața la 8 seara. Tata a adus ceva bun de mâncare de la mama. Mă chinui să nu fac o față disperată, pentru că azi ar fi fost ziua în care aș fi putut primi vizite în rezervă, cu bebelușul alături. Îi spun că aș vrea să iau copilul în brațe. Îmi spune că sigur e ok, mai e un pic, cine știe ce motive au ca să mă țină așa, o fi mai sigur. Pleacă și – iar se târăsc orele…

Trece tata, care se amuză povestind cum i-a reparat o unealtă portarului și a fost lăsat să intre fără mari întrebări. Deși e weekend, deci program de vizitare de la 10 dimineața la 8 seara. Tata a adus ceva bun de mâncare de la mama. Mă chinui să nu fac o față disperată, pentru că azi ar fi fost ziua în care aș fi putut primi vizite în rezervă, cu bebelușul alături. Îi spun că aș vrea să iau copilul în brațe. Îmi spune că sigur e ok, mai e un pic, cine știe ce motive au ca să mă țină așa, o fi mai sigur. Pleacă și – iar se târăsc orele…

După masă vine Andrei. Am urcat cu el – și fară el – la etaj de atâtea ori, acolo, unde după o ușa de sticlă sunt bebelușii… Însă nu prea aveam cui să cerem nimic. Au trecut 48 de ore de la operație deja. Odată am cerut hotărați să-l alăptez, dar ne-a întrebat asistenta de acolo în ce rezerva sunt și nu am știut să spun. S-a prins că sunt încă la reanimare și a zis “Vă credeți la privat aici sau cum? Nu aveți voie să alăptați daca mai sunteți încă la terapie intensivă. Cine știe ce medicamente aveți în corp. Nu riscăm.” Deși sunasem intre timp pe doctorita mea buna și drăguță, care a spus că nu e contraindicată alăptarea, dar…pe tura asta nimeni nu-și asuma răspunderea!

“Să bei multa apa, ca să se curețe urina mai repede” mă sfătuiește asistenta drăguță și voinica.

Încep să beau apa, dau gata sticlă după sticlă , urina e tot rozalie. Doctorul de gardă spune că nu e încă bine, mai încearcă. Hai, că azi iți dam bebelușul. Mai capăt o punga de ser în branulă. Ca premiu, îmi scot în fine sonda..!

Acum situația trebuie monitorizata atent și mi se spune să beau mai multă apă, ca să se curețe urina, și să merg din oră în oră la toaletă. Unde e musai să fac într-o sticla, păzită de o infirmiera stahanovistă care mă observă atent, ca să nu fac vreo trăznaie, în timp ce fumează pe geam. Nu există capac de WC, sticla rămâne după ușă sau uneori trebuie le-o arăt asistentelor, care se poartă de parca aș fi făcut ceva greșit. Îmi spun că “uite câtă încredere avem în tine, faci singură la WC”.

La anul fac 40 de ani. Am fost în Haiti și în India, am văzut mizerie destulă și m-am descurcat, nu e un capăt de tara, mă descurc și acum, vreau la bebelușul meu, sunt dispusă să fac orice. S-o fi întâmplat ceva cu el și asta e doar teatru, ca să îl repare între timp? Când pot să-l văd în fine? Ajunsesem să întreb pe oricine.

Geamul de la WC e deschis mereu, pentru că aici se fumează ca la liceu. E frig și pute și mă chinui cu sticla. Cineva spune că era mai dură doamna doctor de azi noapte, pentru că a pierdut pe unul din copii. Dar eu nu am nici o vină. Ce o face Luca acum? Au început să mi se umfle sânii din ce în ce mai rău, când stăteam în pat, laptele curgea prin țesătură. Colostrul, ce ni s-a spus la curs că e cel mai important. La toaleta mă întâlnesc cu fetele care erau înainte în salonul meu, abia se țin pe picioare. “De ce nu ți-au dat încă bebelușul? Ești mult mai bine ca noi.” Nu mă lasă nici să-l văd, mi-au dat lacrimile. Câți bani le-ați dat voi ca să vă dea în fine bebelușii în rezerva? Îmi rămân cuvintele în gât. Ies pe hol.

Din când în când vorbesc cu ai mei, încerc să le dau impresia că totul e ok. Să nu sufere și mama. Dar probabil mă simte. Nu știu pe cine să întreb ce să fac ca să ies odată din situația asta. O asistentă (infirmieră?) care fumează la WC rezemându-se pe o matură îmi spune, “hai, mai încearcă, acum avem rezervă liberă, e goală, te așteaptă numai pe tine – dar nu e după mine”.

Încerc! Încerc! Beau sticla după sticla, sunt 5 litri de apa deja și 1,5l de ser au curs prin branulă. Îmi explodează sânii în curând, creierii, totul, îmi vine să mă așez pe jos în WC, în sânge și-n urină, mizeria umană e mai rea decât orice.

Când se uita la mine, asistenta spune, “nu mai face așa o fata, că sperii colegele de salon, de ce să sufere și ele? Ce-ai? Te pomenești că ai făcut vreo depresie post-natala!”

“Vreau să-mi văd bebelușul, au trecut trei zile deja de când am născut!”

“Toate la vremea lor, nu e după tine, toți avem bunavoință, nu vezi?”

Laptele picură prin cămașă, pe picior, urina e tot rozalie. Mă gândesc să o diluez cu apă, dacă tot mă bănuiesc nebunele astea.

Andrei vine disperat: paznicul de la poartă i-a spus că nu poate intra la mine, că “duamna e pe masa de operație”. (De fapt, nenorocitul voia bani de o cafea! Dar nu știa cum să îi ceara altfel.)

După ce-mi povestește asta, Andrei începe să mă întrebe dacă poate nu facem destul, poate nu cer răspicat ce vreau. Trebuia să întreb mai devreme doctorița. Ferm! Trebuia să treacă peste mine și să o sune el. Am întrebat, am cerut! Dar nu destul de răspicat, spune el. Prea târziu, mă gândesc eu.

“Ți-au pus prost branula, se sparge vena în curând, uite.” Asistenta mută branulă pe mâna cealaltă, mormăind despre incapabilii care lucrează aici. Câtă apă mai beau? Ce fac cu laptele ăsta? Când îmi dați bebelușul?

Seara la zece și ceva, când nu mă mai așteptam, trece o prietena bună cu consortul, spontan. Nu știu cum face, dar o lasă la etaj la Luca! Mă vede disperata și aranjează cu asistenta mare, care vorbește cu asistenta de sus și mi-aduc bebelușul, înfășurat într-un scutec uriaș ca într-o față de perna. Se fac poze, îmi vine să plâng de fericire. E prima oară că îl iau în brațe pe Luca! Există speranță, mâine sigur mă mută în rezervă și mi-l dau. În fine!

Mai e o noapte, parcă cu moralul mai sus, încerc să amușin dacă s-a păstrat puțin miros de bebeluș pe cămașă, mă uit la poză până mi se împăienjenesc ochii.

Adorm în fine.

Ziua 4. Duminica. Lapte.

Azi nu se fac externări! De asta nu se eliberează rezerve și de asta nu mă mut nici azi! Când am aflat asta, m-a apucat o disperare profundă și grea. E nedrept, nu mai pot sta decât pe spate de atâta lapte, un etaj deasupra mea, unde nu am voie, copilul meu e hrănit cu biberonul și eu nici nu am voie să-l țin în brațe.

La cele doua lăuze din salon vin pe rând doi popi și o matroană voinică, se asează toți pe rând direct la mine pe pat, fară halate și fară să-ntrebe. Popii vin după slujbă, precis s-au frecat de ei vreo 200 de oameni deja, iar asta e o secție de terapie intensivă! Cu sânge și lichide la vedere. Geamul rămâne închis, sunt 30 de grade, vreau măcar să mă pot dezbrăca.

Trece doctorița mea, caută o soluție, trebuie să mai am un pic de răbdare, mă apuca plânsul, vreau să scap odată, încep să mă întreb daca sunt într-un coșmar și de fapt nu am născut încă. Încerc pentru a nu știu câta oară să citesc un pasaj din memoriile lui Hadrian, dar văd că nu mai pot descifra rândurile. Plâng în surdină cu fata la perete, ca să mă lase odată în pace infirmierele cu observațiile lor cretine despre cum supăr colegele de salon cu purtarea mea ciudată, depresivă. Am ajuns la “learned helplessness”. Tot nu am voie la Luca! Deși acum nu mai e nici urina, nici nimica!! Cer să-l alăptez și mi se spune, “să vedem. Nu știm dacă putem prelua această răspundere, dacă Dvs. sunteți încă la reanimare…”

Fac o criză de furie, care se schimbă în bocit, anunț familia că nu vreau să văd pe absolut nimeni până nu iau copilul în brațe. Stau cu fața la perete și bâzâi în gol. Când o să se termine în fine? Într-unul din rândurile când mă duc sus să cerșesc copilul, aflu că a făcut icter, deci oricum l-ar ține sub lampa UV, deci e mai bine pentru mine să mai aștept…

Mă scutur și mai încerc odată. Până la urma aflu că mi-l vor da la alăptat! La 3 ore odată să urc la etaj să îi dau lapte. Însă sânii mei nu mai fac fata, s-au înfundat căile mamare, engorgement, trebuie pompe și masaj și moașe iscusite ca să-și dea drumul.

Trece doctorița mea și face în fine posibil să fiu mutată într-un salon. Însă e îngrijorată de cum mă vede, se miră de povestea cu sonda, vede vena spartă și brațul umflat și decide să nu stau singură, așa că mă muta într-un salon cu alta tipă. Frigider! Mai puțin de 30 de grade! Aer! Unde e Luca?

Așa întâlnesc o moașă drăguță care mă ajuta mult. Ei îi povestesc pasul meu, cu toate complicațiile. După 8.5 ore de masat și tras de sâni cu 2 moașe și consortul, (“de ce nu te mulgi singură, ar fi mai ușor!”), cu lapte țâșnind pe pernă și cearșaf, curgând pe jos, umplând pahare care ajung la chiuvetă, în fine situația e cât de cât restabilită, laptele curge, cu mari dureri, iar la vale.

Mă duc în salonul de alăptat, mai devreme decât celelalte mămici, pentru că trebuie să stau întâi câte 20 de minute la mulgătoarea electrică, “să dea drumul la sâni, că-s angorjati și bebe nu poate trage”.

Acolo sunt niște femei care se știu bine intre ele și pompează o cantitate plina într-un sfert de ora într-un recipient. Apoi dau laptele la un ghișeu și pleacă, fiind înlocuite de cele care alăptează normal bebelușii, pe care-i primesc de la același ghișeu. Într-un rând, primele s-au luat de mine că vin și-mi pun șorțul de alăptat pe piele, nu peste haine. Că e neigienic și să-mi fie rușine de nenorocită. Rămân cu gura căscată la atâta ură, dar tot nu înțeleg nimic.

Aveam să aflu că ele sunt mamele bebelușilor de la terapie intensiva, prematuri și cu probleme. Toate, fară excepție, sunt fumătoare înrăite, care pleacă de la muls repede la o țigară în fața spitalului, în stradă.

Aceste femei vin mereu la și jumătate, apoi la ora întreagă vin cele care alăptează. Cea mai drăguță e o roma de 16 ani, cu un copil mic și cuminte, cu ochi mari și care bea cel mai bine. Prunăreasa. Cea mai tristă e…femeia care era de miercuri în salon. A născut abia sâmbăta, natural! După 3 zile de contracții tot nu se dilatase mai mult de 9 și până la urma a reușit așa. Bebelușul ei e singurul mai mare decât Luca, are 4.6 kg și e așa obosit în urma travaliului încât nu poate suge. Femeia se mulge disperată și pune în biberon, în timp ce copilul îi atârnă moale în jos pe genunchi, dormind mereu.

Luca e ca o omidă cuminte, înfășat până la gât, abia crapă ochii nopțile, dar bea bine. Parcă nu mă pricep deloc, uneori mă întreb daca oare îl țin bine, cu coloana în ax, când alăptez sau e cu capul răsucit la spate, ca o bufniță?

Mă simt ca un animal neajutorat și îi vorbesc copilului, mai mult ca să mă liniștesc și poate ca să bea mai bine. “De ce îi spuneți “piticule”? că doar e uriaș…” întreabă Prunăreasa de lângă mine. “E de doua ori cât al meu…”. “Păi dacă l-am făcut târziu, e mare, na.” Văd că încep să-mi revin încet, daca mai încape și loc de glume.

Ziua 5. Luni. Hârtie.

Ziua următoare e luni. După alăptarea de ora 6 și 9, sunt mult mai încrezătoare: azi se fac externări!

Luca e livrat în rezervă pe la 10, fară vreun avertisment. E așa mic și adormit și totuși e uriaș pentru un bebeluș. Nu înțeleg cum încăpea în mine acum 5 zile. Cică a făcut torticolis, tocmai pentru că nu mai încăpea bine și stătea înghesuit.

Dacă ne dă voie…am putea merge chiar azi acasă. Îndrăznesc să sper. Așa aflu că avem neonatoloagă, văd cine e, aflu că a întrebat din prima zi “unde e mama acestui bebeluș?” și i s-ar fi răspuns mereu că “dna Hasnaș e prea slăbită ca să se dea jos din pat”! Nu primește bani. Am uitat de anestezistă.

Ce multe s-au întâmplat zilele astea, parcă n-o să mai fiu niciodată aceeași. O să rămân cu aminitirea că m-a frânt sistemul în cel mai nepăsător mod. Că n-am știut să mă descurc mai bine, că am fost o fraieră de bună credință, care a luat de bun ce spunea orice troală. N-am știut poate cui și cât să dau și am încurcat algoritmul, de aceea a dat cu virgulă… Am făcut în schimb tot ce mi s-a cerut. Ce naivă.

Când vine Andrei, îi spun, “luăm copilul și fugim!”. Totuși să facem actele, spune el. Se duce la toate instanțele necesare, de unde mă suna să mă întrebe despre numele facultății absolvite (doamna care completează formularul nu crede că așa se cheamă facultatea din Karlsruhe) și despre religie (doamna nu poate scrie “ateu”, “că doar ești botezat!”) și vine înapoi cu o poveste complicată: când era acolo în birou, au dat buzna peste el bodyguarzi care puneau presiune pe doamna incredulă să completeze un certificat de naștere pentru un tată minor, care a făcut copil cu o majora și acum nu poate semna actele. Pentru că e minor și părinții sunt la munca în Spania. …Bodyguarzi!

Avem actele, avem copilul, ne luam rămas bun de la colega de rezervă și fugim.

Afara mă mai uit odată la spitalul de coșmar. E lângă Colectiv. Fugim acasă, sunt frântă.

Acasă mă uit la pachețelele pregătite cu atâta drag și generozitate de mama pentru asistente. Cafea, ciocolate fine. Îmi frânge sufletul. Nici nu am apucat să ne gândim la asta. Ar fi ieșit lucrurile altfel? Femeile alea se purtaseră rău, indiferent ce le dădusem.

Încep să despachetez hainele, vreau să desfac tot ce-mi amintește de acele zile, spăl câteva haine pe care nici nu le purtasem, arunc tot ce pot. Numai când văd ceva ce-mi amintește de spital mă apuca greața. Văd urme ale vieții mele dinainte de aceaste zile și-mi dau lacrimile, necontrolat. Ce iluzie e totul!

Copilul însă doarme liniștit. Nu avem nici cea mai vaga idee cum trebuie schimbat un scutec sau îmbrăcată omida. Motanul se uita îngrijorat la făptură care din când în când tresare în somn.

Mă simt de parca m-am dus până la piață să iau pâine și m-am întors acasă cu un lansator de rachete. Fară instrucțiuni de folosire, și toate rachetele-s armate, gata să explodeze. Dar suntem în fine acasă.

Mai târziu m-au ajutat: moașa-consultant de lactație, motivul pentru care am și azi lapte, după jumătate de an. Doctorița bună și drăguță, cu care încă nu am putut vorbi despre ce s-a întâmplat. Mama și tata, care au trecut pe la noi, practici și puși pe fapte, nu întrebări. Var-mea, în prima zi când a trebuit să plece Andrei de acasă. Cuplul genial care mă ajutase cu testul. Prietenele care au născut înaintea mea. Și încet lucrurile au intrat în normal.

Însă când mă gândesc că pentru a face încă un copil, ar trebui să mai trec odată prin asta, mi se face frig. Și greață.

[1] Testul, care e important pentru femei trecute de 35 de ani, costa in jur de 300€ in Germania, in Romania insa se pare ca o firma are monopol asupra procedurii si decide face pretul.

Déjà vu

Déjà vu (deɪʒɑː ˈvuː) in French, literally, already seen

a: the illusion of remembering scenes and events when experienced for the first time

b: a feeling that one has seen or heard something before.

The frosty sound to go with it here.

Walking through Predeal, the mountain resort where we went skiing when I was 7 years old, I find so many things have changed. The old sloped streets, once so familiar, are now lined with new villas, built mostly in a cheap nouveau riche style, so obvious for impressing and not for comfort. Nauseating amounts of money were buried in some disastrous designs. Their roofs are droopy with huge icicles, as if the people who built them were incapable of realizing the importance of proper drainage. Among the follies there still lie some abandoned old hotels I used to know rather well, a building that looked like a traditional inn, but also a newly built datcha-like thing with little onion tops, and a handful of raw concrete hulks stopped in the construction process, lying around gaped at the sky like stranded whale skeletons.

Walking through Predeal, the mountain resort where we went skiing when I was 7 years old, I find so many things have changed. The old sloped streets, once so familiar, are now lined with new villas, built mostly in a cheap nouveau riche style, so obvious for impressing and not for comfort. Nauseating amounts of money were buried in some disastrous designs. Their roofs are droopy with huge icicles, as if the people who built them were incapable of realizing the importance of proper drainage. Among the follies there still lie some abandoned old hotels I used to know rather well, a building that looked like a traditional inn, but also a newly built datcha-like thing with little onion tops, and a handful of raw concrete hulks stopped in the construction process, lying around gaped at the sky like stranded whale skeletons.

I prefer the old chalets with dark wooden walls and colourful shutters that still look so cosy. Back in his early days, father had come here so often to ski and party with friends or family that he can still recall stories about almost every house on the long, arched Balcescu Street. Many of them were abandoned now, one could see no trace of footsteps in the snow, neither coming through the garden gate nor going up the stairs to the entrance door.

Some shutters were loose and windows open here, paint was flaking off there; one looked as if a fire had raged through the roof. Most of them still had lace curtains in the windows! A friendly orange dog came out of one that had red borders painted around the white window frames and doors. The gate leaves were missing from their hinges. After a while, a whole dog pack followed: 5 of them went out into the street, looking busy.  And then there was this villa with the three-partitioned windows and green shutters with a cute little pattern. The entrance canopy looked intact, but one door was ajar. A window in the top floor was open, too. There were -6°C outside. A faded metal plate was still advertising for a soft drink no one under 30 has ever heard of. In a corner, the name, Vila Banta, was still visible, painted in black letters on golden background, adorned with the logo of the national tourism agency.

And then there was this villa with the three-partitioned windows and green shutters with a cute little pattern. The entrance canopy looked intact, but one door was ajar. A window in the top floor was open, too. There were -6°C outside. A faded metal plate was still advertising for a soft drink no one under 30 has ever heard of. In a corner, the name, Vila Banta, was still visible, painted in black letters on golden background, adorned with the logo of the national tourism agency.

Tourism had started in this area in 1852, when Predeal became border town between Romania and the Austro-Hungarian Empire/ Transylvania. A railroad built in 1874 was meant to bring the young monarchy closer to the empire; soon a station followed. In 1900, the first skiers arrived: some came from Brasov, but most arrived from Bucharest. It is said the ones who could afford skiing in Switzerland came here to practice. Three years later, the first contest took place: every year, new slopes and routes were made accessible, for downhill as well as cross-country skiing. In 1925 Predeal counted little more than 1500 inhabitants. Mainly built in the 1920es and 30es by the wealthier families of Bucharest, who spent their summers by the lake in Snagov and their winters skiing in Predeal, these chalets had seen Christmases and New Year’s Eves until their owners had been chased away by the communists after 1946. Then, nomenclature had made itself comfortable for the many winters to come, hardly ever fixing any tile or faucet in all those years.

In the 1960es there had been grand parties here. The new aristocrats, the apparatchiks, had spent their Christmases here. The same ones who preached against the bourgeoisie and religion and praised equality and the working class were having feasts here where they would stuff themselves with what the others did not dare to dream about.

Every day on my random walks I’d suddenly find myself passing this house again and again, wondering what its rooms looked like, with their wooden floors and wooden beds, mattresses and lace curtains rotting away inside as the seasons passed. People had fallen asleep in those beds, dead tired after a day on the slopes and half a partied night. Why this particular one, I couldn’t tell.

Had this house been nationalized in 1947 and the family that once owned it never told their children about it, in order to protect them? Or were there no heirs, but only a very old and weary man, who had reclaimed it in 1998, but couldn’t afford it anymore, now that he got it back after 18 years of trials?

One of these villas is falling apart, because its owner is a 93 year old who’s too weary to come and see what’s left of his beloved winter cottage of his youth, Rândunica.

Maybe he’s too tired to visit the decaying monument of his memories. The young German girl he once kissed in the room upstairs had married someone else, sold all her jewellery and tried to flee the country in the 50es. They got caught and sent to labour camps, where she died 6 years later in Miercurea Ciuc. Another wintertime love he had once brought here had started dating an officer who was involved in “housing redistribution” – now proud owner of a handful of houses all over the city – and a few wrinkles more. His wife had died of cancer 15 years ago. What use was it, looking back?

In the evening, I called grandma and told her about my walks through Predeal. Oh, yes, your grandfather had worked hard at refurbishing these houses, back in the day, some 46 villas for the you-know-who’s. In the 60es, you weren’t even born. I remember it well, even the drapery samples, the greens and yellows. I’m sure there are some furniture sketches still to be found, neatly archived somewhere among his bookshelves.

In the summer of ’84 my grandparents and I visited Predeal, staying at hotel Rozmarin. From that balcony in the second floor my grandfather had taught me how to pinch cherry stones over the heads of unsuspecting pedestrians on the alley in front of the hotel. The Rozmarin shines with a cheesy, blue-lit spa sign now.

Every day we’d take the Polistoaca, a trail in the woods by the creek, were he built little dams out of gravel, which changed the watercourse. There he’d teach me how to make paper boats that would sail downstream. On our way back, we had walked past that cottage. Once we saw somebody come out and bark at us, why had we stopped there. Grandfather started a conversation, getting them to let him in eventually.

Those green shutters. I had been there before.

***

Today some of the houses are for sale. For instance, Vila Panseluta (the ‘Pansy’) is up for sale by the state protocol administration on the internet for 230’000€: “Villa Predeal, 13 rooms, 9 bathrooms…”

Weeds

Once there was a house standing over here and people living in it. Laughter was heard and there was the swish of dresses and steps scurrying over the stairs; someone would open a window and call the children to the table, in winter it smelled of log fire and in summer of stew. They were all thrown out into the street one spring day without prior notice and scattered away.

The next inhabitants moved into the house. They were many, glum and more savage. These new people wore boots and didn’t draw the entrance door nicely behind themselves anymore: slamming would latch it shut anyways. Strangers to one another and leery, they’d share the bathroom and the kitchen. The eggs and the flour were only for some and did not suffice for all. The house seemed to have more locks and latches now than ever before. A small dog in the yard, some chickens behind the house, and by the end of the summer the cabbage barrel was overturned, so the neighbors would get its smell floating in the air for three days. Crossing old Costache’s yard, rats would pay visits to the hen-coop. They’d quickly steal something from there and run back past the fir tree on their scrawny little feet. Like the new man, they didn’t seem to draw doors closed after themselves anymore: they didn’t need to.

As times changed, these inhabitants disappeared as well. New owners put guards at the gate, so nobody would trespass. They raised the fence higher. Behind it, the house could no longer see into the street. But it didn’t play any role now, all the new owners cared about was its land. The empty house grew more and more sad. Sometimes, a poor man would come hide and sleep upstairs on a mattress, guarded by a shaggy dog. Pigeons had started to nest in the attic.

One night, while everybody was busy with their Christmas baking, the house was set alight. Although you could smell the smoke through the closed windows of the police station on the corner, the firemen took their time to get there and only arrived the next morning… They hosed so much water on the house that its roof came crashing down, taking with it the floor were there once were the children’s rooms and the master bedroom, and bringing it one floor down to the large living room where the Ionescus lived until the 1977 earthquake.

The following winter, people came with machines and razed down what was left. In spring, ashamed, plants struggled to cover the remnants of the house: first a few timid weeds gathered, then the foul smelling ailanthus came with his sisters, the acacias. Together they slowly crawled over the charred pile. Now they’re all hiding behind an even higher fence. Everything is defined by its fence in these times.

The House

Once upon a time, I passed this house on a central street in Bucharest with my grandma. It must have been around 1986 and we were on our way to visit grandma’s friend, Olga, who lived in the old town.

The house was one-storeyed, with several rooms aligning in an L-shape on the corner of a busy street with a narrow pavement. The street windows started at a low height, as if its residents were leaning on the passersby’ shoulders from inside their rooms. A crest placed between two windows adorned the main facade.

In the back, a derelict garden with a cherry tree and some junk gathered in the corners showed that several inhabitants shared the space and that they were probably not living well together.

‘There used to be a piano in the round room once’ grandma suddenly uttered, without any introduction.

‘How would you know? You were in the house once?’

‘They used to play the piano in the room on the left, when you walked in, sometimes when they had guests. Then they danced through the rooms, through the large double doors, from one room to the next…It was a long time ago. Now different people live here.’

Then I forgot all about it. Years passed, the regime pretended to change and brought along decade long trials for recuperation and ownership. Grandma was getting old and tired, but decided to fight for the house that once belonged to her aunt who had run away and never returned.

So we got the house, but only partially. In the middle section, according to law no. 112, an old inhabitant was allowed to go on staying there, without paying any rent, occupying the bathroom and living room. In order to go from the kitchen area in the back of the house to the front rooms, one had to pass through the garden. Just before the old guy died, he brought in his daughter, an alcoholic who kept living there for a few years, still without paying rent to anyone, neither to the state, nor to us. That was not according to the law, but every trial phase she was supported by a rich investor who wanted to build a hotel over a few lots there and had planned the entrance to the parking garage on the place of our house.

By now all our funds were depleted by the trials and maintenance costs and we had but one solution for dealing with the house, besides selling it: let someone live in it for the effort of taking care of it, fixing its leaking roof and draughty windows. So, a young couple moved into the non-linked rooms. They had to cross the garden to go to the loo in the back every time, even in wintertime.

More years passed. One day, the tenants called and told us there was a strange odour coming from under the drunkard’s door. The woman had passed away days ago, without anybody checking on her.

Police came, the forensics came, the neighbours came, but nobody wanted to be the one to open the door. Mom had to do it in the end, like so many other things that nobody else wants to do.

A few days passed by and suddenly some unknown relatives of the deceased showed up and claimed the tile stoves. Dad chased them away.

By the time the couple moved out, their daughter had already started school. Their living there had saved the house from being burned down: on several occasions, especially on public holidays, someone had put fire to the house from three different sides.

Now the house looked battered, but was finally ours to use. After some more renovations, I lived and exhibited in it for a few months, and then it was rented out.

On some mornings I wake up under the impression I’m still living there, in the old house that always welcomed guests so generously.

Chaos*

Bucharest, 1945: Life goes on in a more orderly fashion again, day after day unfurling more or less neatly among the ruins.

One day, out of the blue, while he was waiting at the traffic light on his way home, a guy walked up to him and pointed a gun at his chest, telling him to get out and leave the car. His car. The one he had ordered from the US, after all those years of hard work.

When it finally arrived, everybody had tiptoed around it for days. The elegant silvery coupé with the red upholstery, where she’d lean her lovely head on, tired after a ball. The hatch in the back, where the kids would squeal with joy when he’d take them on a day trip to wherever, the…

All those days in winter he’d driven his family up the mountains, all those summer afternoons to the hills and beaches…Then this guy had just climbed behind the wheel and driven away, his dirty hands clutching that wheel he used to stroke! Now he’s walking aimlessly in the streets, a vague idea he should go home and tell her that…the car was gone. A guy in a uniform had asked for it and he…he had pointed his gun at you.

He hated the war, it was finally over – and now everything just got a whole lot worse.

*cha·os, noun: complete disorder and confusion. Disorder, disarray, disorganization, confusion, mayhem, bedlam, pandemonium, havoc, turmoil, tumult, commotion, disruption, upheaval, uproar, maelstrom.

In physics: behaviour so unpredictable as to appear random, owing to great sensitivity to small changes in conditions. The formless matter supposed to have existed before the creation of the universe.

The Caretaker

The winter of 1985/6 was one of the coldest here – much like this one. Temperatures would fall considerably below -18°C outside and quaver around 12°C inside, thanks to the state imposed austerity programme.

Invariably, end of January the winter games between the state-owned enterprises would begin. The ski cups were initiated in 1952 and are still held today: ‘Cupa IPA’, ‘Drumarilor’ (Road Workers’ Cup), ‘Proiectantul’ (the Draftsman), ‘ALFA’. Participating as a team on behalf of their factory, IMUC, the Chemical Equipment Installation Plant of Bucharest*, dad and his colleagues would get accommodation in Predeal and where exempt from work for the duration of the cups. So they’d take their kids and spouses along and we’d pack the cars full with everything necessary, from complete ski gear and food to sleeping bags, pans and gas burners. Unlike today, back then there was absolutely no guarantee that you could find a restaurant with food in the winter sport area – nor anywhere else, actually.

There wasn’t even a guarantee that you’d get where you wanted to, as Militia de circulatie would close the main roads in districts ‘affected by snow’ more or less randomly, cutting people off in the middle of their voyage on a Sunday (the only free day, as there was a 6 days workweek) and leaving them to wait for hours, sometimes days, in some valley (the Prahova Valley, usually), with no particular regards to the state of the roads or the weather forecast.

This time we had made it to Predeal rather easily: dad said it had probably been too cold for the militieni to come out.

The first evening, after getting a sandwich and brushing our teeth, us kids huddled together in a big bed under layers of sleeping bags that smelled like home and remotely of mothballs, while the parents tried to insulate windows and doors with some holey blankets they found in the villa.

The food we had brought along was placed between the windows: some bread and ham and raw eggs. Then the grownups gathered in the hall for a chat, a drink and cigarettes. While waxing the skis!

I think I was about 5 years old and the boy was 3 or 4. My parents had already said goodnight to me and now this lady would tell her kid a bedtime story. But he wouldn’t fall asleep, he wanted to play and maybe have another sandwich. His mom finished her story and tried lulling him to sleep – it just didn’t work.

After a while she lost her patience and I heard her say in a menacing tone:

‘Daca nu esti cuminte, sa stii ca te dau la administrator.’ – ‘If you don’t behave, I’ll give you to the caretaker.’ The boy whimpered and shut his eyes tightly.

Suddenly alarmed, I had to know: ‘What caretaker is that?’

‘Shht, it’s bedtime now. The one from our block.’

‘And he takes kids away? Where does he take them to?’

The boy winced again, pressing his eyes shut even tighter.

‘Yes, he takes kids away if they don’t behave. Now shush and go to sleep.’

‘But… but my parents never told my there was such a person as the caretaker. Where does he come from?’

‘Yes, there is. He lives downstairs in our block. He’ll take my son if he won’t behave. And you as well. He’ll take any kids who misbehave. Every block has one.‘

The kid pulled the blanket over his head whimpering ‘…the caretaker’.

‘… where does he takes kids to? For how long? And why would you let him do it? Would you open the door?

You don’t have a latch, is there nothing you could do?’

‘…Nobody knows’ where he takes them to, but they never return.’

‘Does he take adults as well? Like my terrible teacher who hates kids? and the neighbour lady who swears all the time and her mean husband who drinks and yells every day?’

‘Go to sleep now!’

I just could not believe her. Agreed, I was not raised in a block of flats, maybe they have strange habits there, but still…

‘Look…I don’t think so. If there was any such man, my parents would have told me so. I mean, maybe there is, but he wouldn’t follow us to the mountains. How would he know where we are? I think nobody’s coming for us.’

There’s rustling under the blanket. Some hope: ‘No caretaker?…’

The lady gets up and walks away. Hisses from the door ‘Now, look what you’ve done, he was almost asleep! He needs his sleep; he’s smaller than you. You see how you get to sleep all by yourselves now. I won’t hear another sound of you!’ Door slams shut. Silence.

‘Hey, psst.’ – Whimpering.

‘Look, I don’t think there’s a caretaker who takes kids away. I tell you, all the afternoon naps I didn’t take and all the evenings I would not fall sleep – nobody came for me; I think we’re quite safe.’

Silence.

‘Even if there was – I don’t think he’d follow us ‘til here… He’d get lost. And it’s way too cold; they must’ve shut down the traffic anyway. Come out.’

Muffled hopeful sound.

’Hey, c’mon, come out and let’s play.

She’s can’t be right, I’m telling you. My parents know better, believe me. There’s no such man as the caretaker.’’

Half a face comes out from under the blanket. ‘But she’s my mum. She knows stuff.’

‘Maybe, but she sure doesn’t know this one. ‘

In the morning a thermometer outside showed -26°C.

The eggs were cut in halves with an axe and placed face down in a pan on the burner in the hall.

We all gathered around to warm our hands and watch the orange rings in the yolk flow out of the shell, as it melted directly into the pan.

It was the funniest omelet I ever had.

___

The ski cups are still being held. The kid got married last year.

And I now know what a caretaker of a block of flats does. He does not take little kids away – but your precious time. Lots of it.

In return, he gives you frustration.

___

*IMUC/later TMUCB was established in 1960 and broken into pieces in the 90es. Some pieces survived till 2011. It mainly produced chemical and petrochemical machinery.

In his position as a design engineer there, dad drafted parts of refineries, a heavy water- and other plants, but also parts of a soap factory, and an over dimensioned rooster for a playground.

Blues

A blue devil passed by

A blue devil passed by

It is said that when a ship loses her captain, she’d fly blue flags.

Today, when a ship is flying the ‘Blue Peter’ in port, she’s actually calling its crew to embark for departure:

‘All persons should report on board as the vessel is about to proceed to sea’.

Blue was first used for sadness in the 14th century, when Geoffrey Chaucer, inspired by a natural phenomenon* described the affair of Mars with Venus in the poem Complaint of Mars. In order to be with Venus, Mars has to slow down and follow all her instructions: he’s not to despise any other lovers, feel jealousy or be cruel ever again. When he complies and they finally get together, the Sun god, Phebus/Apollo, surprises them in bed. Venus flees, in order to avoid the confrontation with her husband. Mars won’t fight the Sun, so he sadly follows Venus, knowing they’ll never be together again and lamenting “with tears blue, and with a wounded heart.”

It is said that people in the 17th century believed that blue devils were responsible for their sadness.

Everybody knows the blues, the music African Americans gave us from the end of the 19th century.

And I’m sure you know that feeling.

Some part of you went missing. You still remember it so well, but it’s gone.

Now the memory’s haunting you and dwelling in it is bitter sweet.

So you don’t want to get out, not just yet. You’re just feeling blue**.

Blue is lonely. You’d want to sing or howl about it,

but do you really need a public for that?

Blues are for honest introverts.

—

* conjunction of Mars and Venus, April 12th, 1385

** not to be mistaken for the German ‘blau‘ = drunk.