My great grandma had come to Romania from Switzerland in 1927.

She was born on the side of the Bodensee in 1904 and had seen Zeppelins flying over the lake; she grew up during the First World War. She was in Bucharest in the 1940 earthquake and during the Second World War.

Communism and the 1977 earthquake found her in a room of the house that I later grew up in.

Witnessing changes and hardship had turned her into a mine of stories.

She’d wake up at 6am every day; take a cold shower and an aspirin, ‘to keep the blood clot-free’, then rush out and sweep the pavement, to the utter amazement of all our neighbours.

Sometimes, they’d greet her with: ‘The crazy German lady is out sweeping again. How’s it, missus?’

‘I am NOT German. Please.’

‘But you speak German.’

‘I am Swiss.

‘Swiss, Austrian, German – all Germans who speak German’, the answer would come back.

‘If you had any idea what fierce resistance the Swiss brought up against the Germans in history, you’d NEVER mistake one for another.’

Then she’d retreat to the garden, muttering ‘Ignorants!’

After sweeping the dust, leaves or snow, depending on the season, she’d come inside, change her shoes and put the battered kettle on, make filter coffee and also give me a cup, with milk and sugar.

Then she’d go to the market, every day, even in the dark eighties, when it had become just social behaviour, as there was hardly anything to be bought from the pale faced peasants after 1984, neither on the stalls – nor from underneath them. She’d make gratins from half a celery, an egg, some old bread and diary product.

She taught me all about gardening, keeping alive a neat garden with flowers more typical to her birth climate, than to the extreme one in Bucharest. Big-leafed bergenia, wild flowers from the woods and hydrangea bushes, they all needed constant maintenance and watering here. Even the roses were of foreign sorts. When we’d go on a visit to one of her friends, she’d bring along a rose from the garden, a gesture I came to appreciate but decades later, after having searched hard for a perfumed garden rose in all markets of the countries I lived in.

While gardening or taking care of the household, she’d tell me stories of places she’d seen and people she’d met along the way. All rather pedagogical, now I come to think of it.

But she was at her storytelling best during lunch. We’d sit in front of her dark bookshelves, just the two of us. She’d serve the gratin and start telling the goriest stories.

About how she came from poor and starving Switzerland, just to find people here throwing food away…even bread! And how she’d tell them that one day they were going to regret wasting food. About how the war came and the people starved and had no shoes. How they had to sell their belongings at the flea market, the beautiful painted teacups and the paintings and the cutlery. ‘Did you have to sell your things, Omama?’ She wouldn’t answer and go on to the next story.

Of the couple that was having a fight during the earthquake. They were in bed and the rattling started. The husband jumped under the doorframe and begged his wife to join him. But she was cross and told him she’d rather die in bed than join him. So the doorframe collapsed and he was crushed and she survived it, in bed!

When my parents came home that night, I asked them why they had told me to shelter under the doorframe in case of an earthquake, if it wasn’t safe anyway.

‘Who told you that, sweetie, ‘course you’re supposed to run for shelter under the doorframe! Not outside and not the staircase, love. It’s the Doorframe.’

‘But Omama said that the husband in the story got crushed there, so it’s not safe. I’ll go and hide in the cupboard or under the bed.’

‘Omama told you – what?’

Next day, great grandma got instructed to stop telling the kid ‘terrible stories, understood? She’s a kid, she’s not to be exposed to horror, got that?’, dad had said.

She told me a few stories about great personalities instead, showing me pictures from one of my favourite book ‘Menschen, die die Welt veränderten’ (People who changed the world), the Westermann edition. My favourites were Homer, Alexander the Great, Aristotle, Henri Dunnant, Mohammed the prophet – lovely Persian miniatures where he’s depicted without a face and with flames around the head, riding horses in the sky. Then, Marie Curie, Farraday, Koch, Tesla. Gandhi.

After a while I knew these people’s stories by heart – and wanted MORE STORIES.

So we got back to gore.

‘So, one of the people who survived the great earthquake was this lady in a bathtub. She fell out of the 3rd floor while showering, you know, and – got away.’

‘She fell…into the street?’

‘Yes, dearie. In March, 4th, 1977. Terrible earthquake.’

‘Oh. In her bathtub’.

I went to play in a corner and…digest this new piece of information.

I couldn’t ask the mighty dad, because I knew meanwhile that he didn’t take earthquake stories well. And mom would cut this short, probably. So I turned the story over in my head for a few days. But it started keeping me up, what happened after she fell, once she survived?

A few days later, I had reached the conclusion that this was, although an ‘earthquake story’, one with a happy ending. So, there was a chance to ask dad.

In the evening, dad came to say goodnight and I tried to bring up the matter. ‘Dad, soo…you know, the lady who survived the earthquake?’

‘…’

‘The lady who survived the earthquake in her bathtub?’

‘Here we go again! Horror stories from – let me guess, Omama?!’

‘But…but this one SURVIVED! I was wondering…’

‘No, please stop thinking about the earthquake, sweetie.’

‘But I can’t sleep without knowing the end of the story!

‘Go to bed. Please. It’s late.’

‘But…it’s been 3 nights I’m wondering what happened after that.’

‘After what?!’

‘After she fell. And survived. Please tell me, dad.’

‘Tell you what? She survived. Go to bed. Now’

‘But…what happened next? She fell out, in her bathtub – aaand?’

‘Survived. Great. Sleep now.’

‘But she fell into the street, on the crossroads! From the 3rd floor!’

‘Goodnight’ Dad was already at the door.

‘Please tell me how the story eeends, dad please! I can’t sleep. She was naked or was she taking a shower with her clothes on??’

‘…’

‘I have to know! It was in March, it was cold outside!! Were the people staring? She was naked in the middle of the crossroad? In her bathtub? Please tell me what happened.’

Long sigh. Best dad in the world turns around and comes back from the door. ‘Sweetie. Somebody probably gave her a coat. Now PLEASE go to sleep.’

I finally slept well that night. And the next day I promised Omama I’d never tell dad about the gory stories again.

I often wondered how the guy who had his face hit by a brick got recognized by his relatives – or how the lady whose silk robe caught fire…

But I never asked dad again.

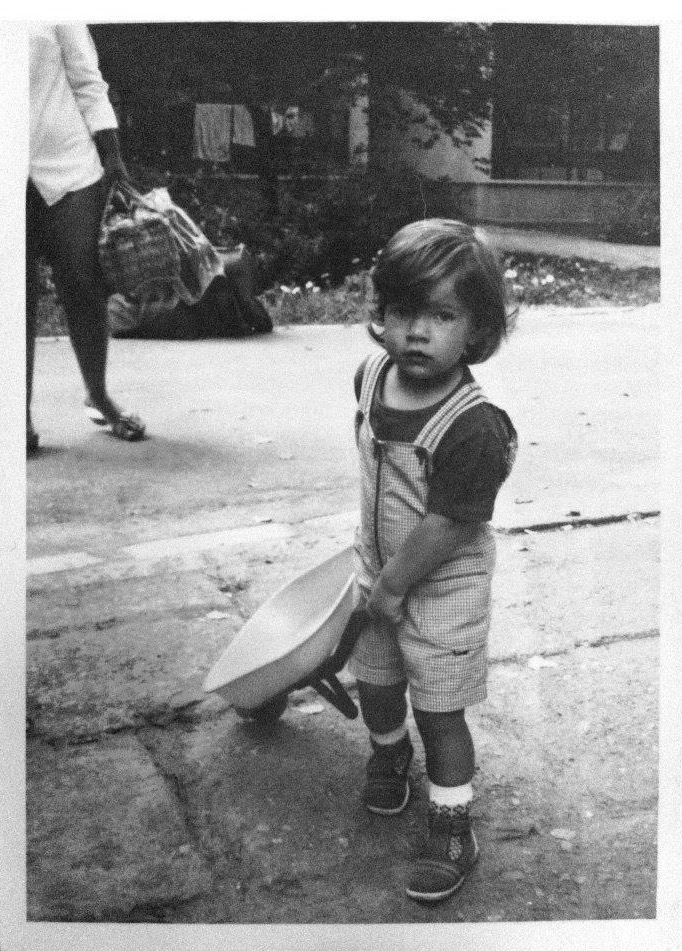

You can see a picture below of the above mentioned Omama and my great grandpa listening to Radio Beromünster in 1946.

He never came home from work at the Pharmacy one night, in 1952. But that’s another story.

***

Listening to Radio Beromünster in 1946

Listening to Radio Beromünster in 1946

Next Thursday, on March 4th there’ll be 39 years since that terrible earthquake, which struck Bucharest with 7.4° on Richter’s scale and killed more than 1’500 people.

Among them was our best comedian of all times, Toma Caragiu.

11’300 people were wounded. 32’900 buildings were damaged or destroyed. The material damage was estimated at 2 billion dollars.

Ceausescu was on a visit in Nigeria at the time and, on returning, used the damages as an excuse to start a demolition program that erased a quarter of the old town center and destroyed the homes of more people than the earthquake itself.

Let’s hope the next big one spares Bucharest, as we all know that houses don’t mend themselves and this city did nothing to enforce its structures and protect its inhabitants since the last one.

A song to go with it here.

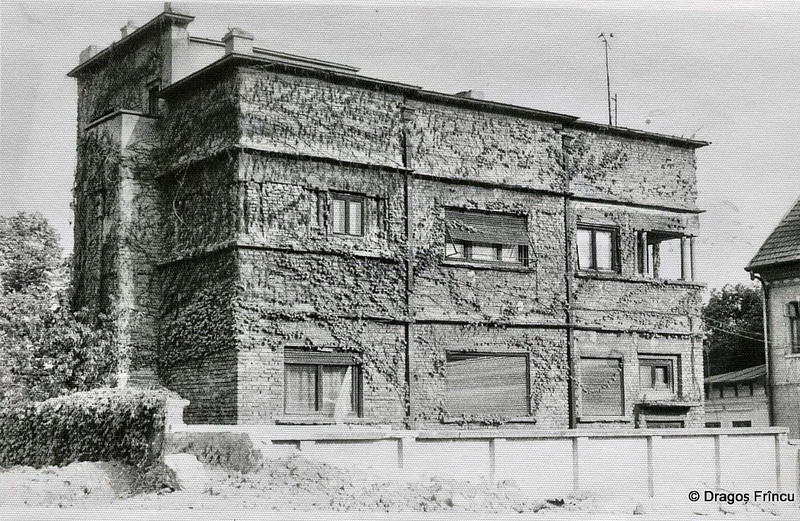

One mild autumn day I was running through the streets that managed to escape the massive demolitions for the civic center in the 80es. These streets once flowed from northwest towards southeast and are all suddenly cut off at weird angles by an axis that was once supposed to become a new Champs Elysees – just longer and, well – national style.

One mild autumn day I was running through the streets that managed to escape the massive demolitions for the civic center in the 80es. These streets once flowed from northwest towards southeast and are all suddenly cut off at weird angles by an axis that was once supposed to become a new Champs Elysees – just longer and, well – national style.

Listening to Radio Beromünster in 1946

Listening to Radio Beromünster in 1946

Gheorghe Panu str. – Schitul Maicilor str. Photo from Mihai Isacescu

Gheorghe Panu str. – Schitul Maicilor str. Photo from Mihai Isacescu

The Uranus Neighbourhood – Minotaurului street in the lower third – THEN

The Uranus Neighbourhood – Minotaurului street in the lower third – THEN …and NOW

…and NOW