Într-o zi o să am în fine masa aia mare la care o să se adune lumea dragă.

În timp au fost câteva mese la care îmi găseam locul.

Masa florentină de la bunica – o masă lungă și aproape neagră, cu desenele mele sub sticlă – cam rece sticla aia – însă se punea fața deasupra, ca un ștergar brodat – aici veneau toți cu povesti, cu frici, cu zâmbete, se întindeau la cafele și dulcețuri – până la urmă se găseau soluții pentru orice. Nu mai e casa aia de o vreme și masa e acum înghesuită într-un apartament.

Masa rotundă cu picior hexagonal de la bunicii din partea mamei, unde mâncai sub privirea blândă și amuzată a străbunicului din tablou. Acolo erau șnițele și preiselbeeren. Și afară la geam atârna o căsuță de păsări făcută de bunicul, mereu asaltată de sticleți gălăgioși.

Masa din parterul întunecos al străbunicii, unde te simțeai mereu ca la jour fixe și stăteai cu spatele drept și ascultai radio și poveștile ei cu zeppeline zburând pe cer, dar și cu morții de la cutremurele și bombardamentele trăite.

Masa alor mei, tot rotundă, luminoasă, odată veselă, însă mereu cumva tensionată și reprezentativă; în ultima vreme doar locul certurilor și al fețelor lungi, peste care se aude constant agitația, “mai vreți supă? vreți o cafea? mai vreți cartofi? aduc prăjitură?”

Parcă nu ne mai auzim demult.

Masa din garsoniera mea de la final de facultate, unde se adunau aproape zilnic prieteni – unii nu mâncau porc, alta era vegetariană, se dezbăteau aici toate subiectele pământului, jucam jocul ăla cu “cine sunt eu?” cu bilețele în frunte. Cel mai bine era că aici se rezolvau probleme și conflicte, ziceau ei. Era loc pentru toți. Eu cică găteam constant pe margine, cu un pahar de roșu într-o mâna și cu pauze de țigară la fereastră.

A fost o vreme masa din Zürich, care sâmbăta era mereu plină cu bunătăți și câteva ziare pe care le aduceam când veneam de la cai, indiferent de vreme. Pe la 11 când se trezea și el, pe mine deja ma lua somnul. Pe după masă veneau prietenii, găteam, poveștile lor se împleteau cu vinul roșu și ultimele idei de proiecte și expoziții.

Nu a fost să fie masa din apartamentul amenajat cu atâta drag în Mântuleasa. Mare, albă, mereu plină – dar venită într-un moment în care nu mai eram noi – eram deja fiecare pentru el.

Acum masa mea e mică, încăpem maxim doi și-o pisică.

Într-o bună zi o să am masa mea mare, cu copii și cu prieteni în jur,

unde se poate așeza oricine vine cu drag și fără țâfnă.

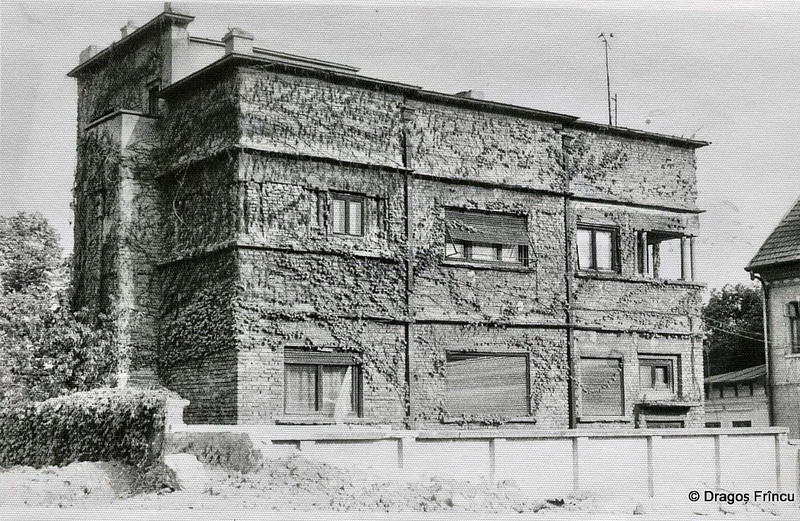

Gheorghe Panu str. – Schitul Maicilor str. Photo from Mihai Isacescu

Gheorghe Panu str. – Schitul Maicilor str. Photo from Mihai Isacescu

The Uranus Neighbourhood – Minotaurului street in the lower third – THEN

The Uranus Neighbourhood – Minotaurului street in the lower third – THEN …and NOW

…and NOW Temple of Bel. 2004No situation describes the actual times better: a bunch of uneducated fanatics runs around blowing up in a matter of minutes what has been put up more than 2’000 years ago with more skill and craft than we can deliver today with modern machinery.

Temple of Bel. 2004No situation describes the actual times better: a bunch of uneducated fanatics runs around blowing up in a matter of minutes what has been put up more than 2’000 years ago with more skill and craft than we can deliver today with modern machinery. Great Colonnade at Palmyra, 2004.

Great Colonnade at Palmyra, 2004. A July morning in 2004, 6am

A July morning in 2004, 6am

Altar. Temple of Baalshamin, built in 131AD. 2004.

Altar. Temple of Baalshamin, built in 131AD. 2004. A lizard hiding in the altar wall, 2004

A lizard hiding in the altar wall, 2004 Destruction in 2015. ©REUTERS/Social Media

Destruction in 2015. ©REUTERS/Social Media